A review of women led humanitarian approach – Conceptions and nuances in the Nyiragongo Territory of the North Kivu Province of DRC

In spite of the central role women play in the survival and resilience of families and communities, women participation and leadership are often ignored in humanitarian actions. It is commonly argued that “paying attention to gender issues may not be timely or practical on the ground”. Until the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit, women and girls had been perceived and seen by many humanitarian actors including women as primary victims of disasters and recipients of humanitarian assistance. This paper, therefore, aims to examine the conceptions and nuances of a humanitarian approach that places women at the centre in terms of preparedness, prevention, response and recovery. The paper is built on a conceptual model of a women-led humanitarian approach which establishes the relationship between the principles of the approach and women resilience to build back better. It tries to provide answers to 1) What is the women-led humanitarian approach? and 2) What are the principles of a women-led humanitarian approach?

Introduction

Humanitarian assistance is designed and delivered with the primary objective of saving lives and alleviating suffering. It is commonly argued that “paying attention to gender issues may not be timely or practical on the ground”. During a humanitarian crisis, differences in the vulnerability of women and men begin to manifest more than before as a result of socially constructed gender roles (Eric and Thomas, 2007). According to WHO (2011), 20% of women are as likely to experience sexual violence in humanitarian settings and more girls are more likely to be pulled out of school during disasters and conflict than boys. It is important to note that, more women are killed than men in natural disasters and at an earlier age. Despite all these in addition to women’s role as first responders to crisis and their central role in the survival and resilience of families and communities, women’s participation and leadership are often ignored in humanitarian actions. However, long-term engagement in humanitarian actions reveals that the entire community benefits when women are included in all stages of humanitarian action (UN Women 2015). Women and their groups are best placed to mobilize change, identify solutions, and respond to crises.

Until the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit, women and girls had been perceived and seen by many humanitarian actors including women as primary victims of disasters and recipients of humanitarian assistance. The 2016 World Humanitarian Summit recognized that women are not only survivors of a humanitarian crisis, but they play a critical role as responders and agents of change including their unique role as the first 24-hour responders in humanitarian crisis (World Humanitarian Summit, 2016).

Despite substantial barriers, when women lead in humanitarian action, the results and impact are a phenomenon. Women-led as first 24-hour responders, campaigners, mobilizers, volunteers, monitors, facilitators and members of community management committees, members of crisis management or relief teams and convenors of women’s groups, individuals, leaders, volunteers, and members of women-led groups and networks. In effect, experience and evidence show that when women are allowed to participate equally in humanitarian actions, the responses are more effective and inclusive. Although Grand Bargain signatories committed to ensuring that 25% of humanitarian funding reaches local and national actors as directly as possible, less than 0.1% of COVID-19 funding currently tracked has done so. This demonstrates that women are constantly left out in humanitarian actions thereby increasing their exclusion in matters and decisions that affect them at all levels. This reduces the efficacy of response thereby exposing women and girls to further risks. It shrinks or eliminates their space to influence and making the decisions that most affect them (CARE, 2020).

Participation of women in humanitarian action increases their confidence and self-worth which are needed during displacement. For the fact, women lose everything including their husbands during humanitarian crises especially conflicts, their only source of pride and hope is their self-worth and dignity. Lack of participation exposes women to various forms of risk including insecurity, abuse, violence, and exploitation. Globally, there are conscious efforts to recognize and increase women’s participation as an essential strategy for effective humanitarian response (CARE, 2017).

Motivation and Methodology

This paper aims to examine the conceptions and nuances of a humanitarian approach that places women at the centre in terms of preparedness, prevention, response, and recovery using the Nyiragongo Territory of the North Kivu Province of the DRC as a case. The paper is built on a conceptual model of a women-led humanitarian approach which establishes the relationship between the principles of the approach and women’s resilience to build back better. It tries to provide answers to 1) What is the women-led humanitarian approach? 2) What are the principles of the women-led humanitarian approach? The paper also makes recommendations to the government, donors, CSOs, and other humanitarian actors on a women-led humanitarian approach.

The paper is based on a review of literature from reference lists and primary information collected from 46 respondents in the Nyiragongo territory of the North Kivu Province of the DRC. They comprised 27 women representatives of women groups, 6 staff of local authorities and cheferees, 10 key informants, and 3 staff of civil society. The Nyiragongo Territory is one of the territories in the North Kivu Territory of the DRC. The North-Kivu province has been the theatre of violent conflict over the past two decades resulting in population displacement and instability. This led to food insecurity, and severe malnutrition (UNICEF, 2012). The conflicts also resulted in sexual violence against women, with more than 7,075 cases of rape reported in North-Kivu in 2014 (UNFPA, 2013). Other problems reported in the province are food insecurity and malnutrition of vulnerable people. The province host over 40% of internally displaced persons in the DRC.

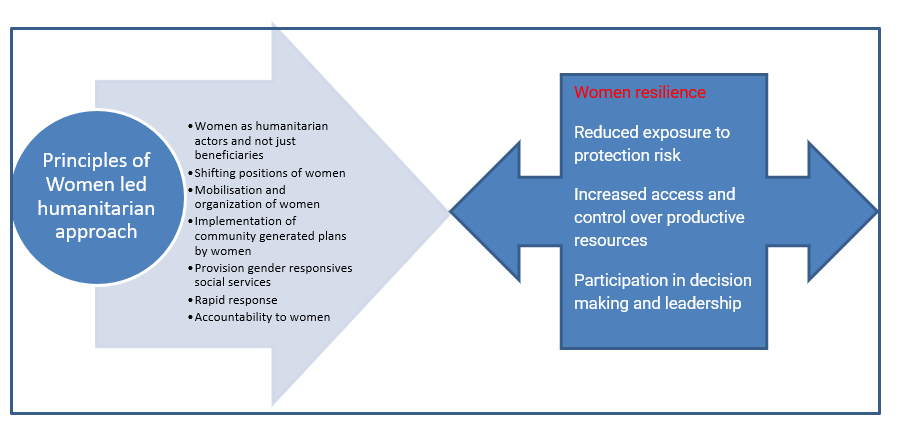

Figure 1: Conceptual model of women-led humanitarian approach.

Source: Field data (2021)

Conceptual model of women-led humanitarian approach

The conceptual model depicts that the principles of the women-led humanitarian approach have differential effects on increasing women’s resilience to build back better during emergencies. How the principles are applied in the approach to a greater extent determines how the approach moderates’ women’s exposure to protection risks, women’s access and control over productive resources, and women’s participation in decision making and leadership. The principles of the women-led humanitarian approach influence the women-led humanitarian approach and women resilience nexus.

Conceptions and nuances about a women-led humanitarian approach

The paper reviewed the experiences of donors, INGOs, community members, and local actors on the understanding and approaches of humanitarian work that recognizes and puts women at the centre. Some refer to it as a women-led humanitarian approach whereas others refer to it as the feminist humanitarian approach. The dichotomy between the two has to do with how the approach is used to ensure women’s leadership in humanitarian action or how women and girls are prioritized due to their vulnerabilities. These terms though recognizably different, the former will be used in this paper.

ActionAid is one of the organizations promoting women’s leadership in emergencies for many years now. ActionAid’s experience of working in over 45 countries worldwide revealed that women’s rights are violated during conflicts, disasters, and emergencies due to their exposure to protection risk. Women become more vulnerable as their needs and rights can be, and often are, overlooked, ignored, and deprioritized in the heavily male-dominated world of humanitarian aid. Despite the critical role women play for the care and emotional rebuilding of communities in the aftermath of a crisis and the strong local knowledge and links with others in the area where they live, their concerns and perspectives are often underestimated and overlooked during humanitarian response. ActionAid, therefore, creates space for women to contribute to the decisions that affect their lives, especially in emergencies. Women make up 50% of the population, but often remain excluded from groups and processes that determine their futures (Sonya, 2019)

In most cases, humanitarian responses remain ‘gender blind’. Women are denied access to vital services and protection thereby increasing their risk of gender-based violence and other protection risks as well as livelihoods. Emergencies aggravate the vicious cycle of disempowerment of women who are most affected during conflicts and disasters. ActionAid experience shows that the wider community benefits from the humanitarian response when women are put in the driving seat. Patriarchal systems that keep women powerless in their everyday lives are dismantled when women are supported to make decisions in emergencies and to speak out when their needs are not being met (Sonya, 2019). This, therefore, calls for a strategic humanitarian approach that is transformative enough to crowd out patriarchal paradigms that relegate women to the background during emergencies. Views generated from respondents during the development of this paper indicate that about 70% of respondents see the women-led humanitarian approach as the humanitarian approach which empowers women and girls as change agents and leaders. 62.5% of these respondents are female. In effect, a women-led humanitarian approach should aim at building the capacity of women leaders in terms of information and knowledge to lead and support other women and communities to realize their rights. Though only 13% revealed that the women-led humanitarian approach is the humanitarian approach that places women and girls at the heart of response, all women regardless of their status should be considered in the humanitarian response cycle.

No woman must be left behind in humanitarian action to ensure that women’s leadership and women’s rights are at the centre of humanitarianism. When women are empowered to lead and take leadership, it reduces their levels of vulnerability by increasing their capacities to cope with hazards. Both vulnerability and hazards are interdependent and the higher the capacity of the individual, the less impactful the hazard. In effect, a person becomes more resilient when he or she can withstand shocks. Gender-responsive humanitarian action can play a key role in recognizing the potential of women and girls. It also supports their collective leadership and agenda of women as powerful agents of change. (Government of Canada, 2020).

According to CARE (2019), humanitarian actors must acknowledge women’s roles as first responders and agents of change in crisis prevention, response, and recovery. It is important to recognize that women are the best representatives of their needs in humanitarian crises and therefore need to be consulted and their views, aspirations, and immediate and strategic needs should inform humanitarian planning and response. Particular effort should be made to avoid sameness by reaching out to vulnerable women, including women with disabilities, pigmies, girl mothers, elderly women, and women of diverse sexual orientation and gender identity. Women should be engaged as active partners and not just as beneficiaries of humanitarian assistance or aid. In all phases of every humanitarian response, governments, donors, UN agencies, humanitarian organizations, and national and local actors should prioritize communicating the value of women-led partnerships and push for systematic and meaningful engagement to promote women’s voice and leadership in humanitarian response. Of those who responded that the women-led humanitarian approach empowers women as change agents and leaders, about 43% fall within the ages of 26 to 30 years. 31% fall within the ages of 31 to 55 whilst 26% are above 55 years of age. For those above the age of 55 years, due to their age and current status as widows/widowers and sick, they did not see the importance of women providing leadership in humanitarian response. They see themselves as beneficiaries whose needs must urgently be responded to.

Humanitarian response must recognize and address issues of unpaid care burden that increases during emergencies. In most cases, displaced women would have to take the additional responsibility of providing security, caring for the injured or sick, and children who are missing school as a result of displacement. Providing cash transfers as both a protection and livelihood mechanism needs to be considered and delivered from a women-led perspective. This includes gender-responsive participation in conducting feasibility studies, targeting, and cash delivery. This approach is very important in promoting women’s leadership and participation in humanitarian response. Humanitarian coordination mechanisms and the humanitarian planning cycle need to also recognize women and women’s organizations as first responders in humanitarian crises. There is no true accountability to affected people without investing in enabling environments that make women’s leadership possible (UN Women, 2020). It is in the light of this that about 9% of respondents interviewed responded that the women-led humanitarian approach is the humanitarian approach that protects, respects, promotes, and fulfils women’s rights. About 9% also responded that the women-led humanitarian approach is the humanitarian approach that delivers gender-responsive services. These responders posit that the approach should prioritize creating a protective environment through the provision of medical, psychosocial, and legal services to respond to women’s needs in emergencies. Basic services such as safe spaces, water, early childhood centres, and accessible markets should also be an integral part of the approach. This will enable women to come together to develop leadership, agency, and collective capacity. Humanitarian response should take the specific needs and strategic needs of women and girls in displacement including access to safe places, access to toilets, and access to local markets. When the needs of women are not met, the entire community suffers.

Principles of women-led humanitarian approach

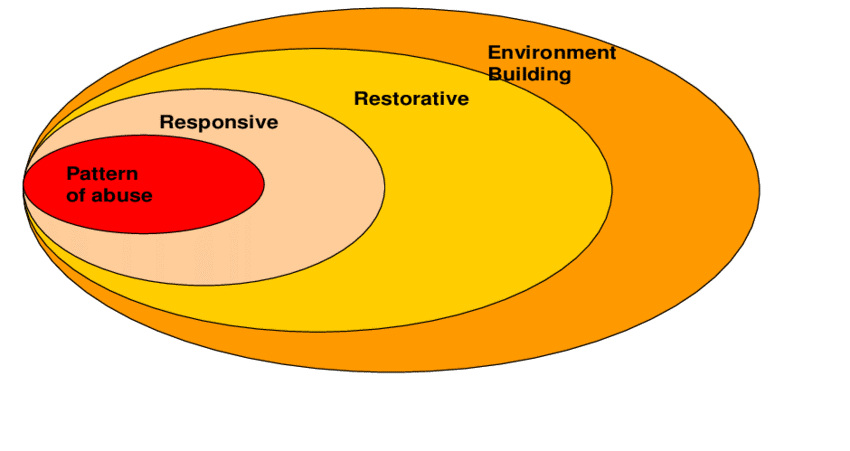

Humanitarian actors are responsible for creating enabling spaces at every level of humanitarian practice or approaches to ensure that humanitarian interventions respond to the immediate and strategic needs of persons of concern especially women and girls. The humanitarian crisis increases women’s risks of violence, coercion, and deprivation of basic goods and services. This paper therefore aligned principles of women-led approach with the egg model to depict what principles are key at each stage of humanitarian response. The egg model depicts various actions in the humanitarian program cycle as shown in figure 2. The principles should guide specific and appropriate actions to ensure that women affected by crisis benefit from assistance in a safe and dignified manner.

Regarding figure 2, responsive actions are interventions or actions during a humanitarian crisis that are geared towards alleviating the immediate suffering or effects of violence and abuse. They are aimed at putting a stop to it and prevent its recurrence. Restorative or remedial action on the other hand is actions or interventions that ensure the provision of basic needs and services, restoration of dignity, well -being and recovery. Undertaking environment-building actions are more rights-focused. They aim at creating a conducive environment to respect the rights of people affected by the crisis. They are actions that seek to transform social, cultural, institutional, and legal environments to be responsive to promoting, respecting, and fulfilling the rights of people affected by the crisis (Susanne, 2008).

Figure: 2 Egg Protection Model

Source: Susanne (2008)

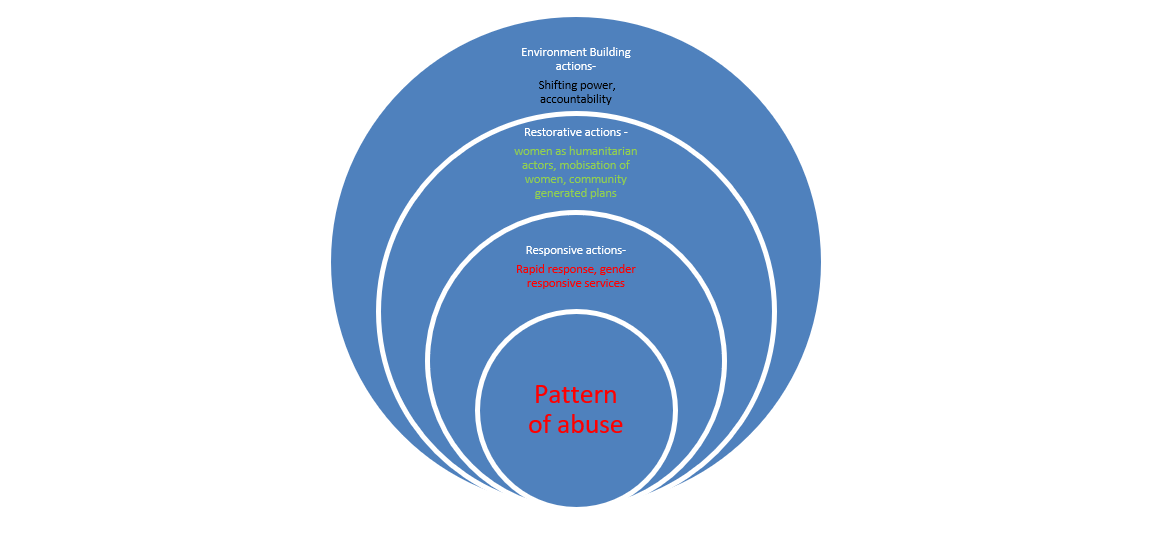

Any approach should therefore be located and guided by principles that seek to reduce their vulnerability and increase their resilience through responsive, restorative, and building environment actions as shown in figure 3. Each principle identified by this paper is placed under the most appropriate action to show its relevance to the women-led humanitarian approach.

Figure 3: Egg Protection Model and Principles of Women-led humanitarian approach

Field data (2021)

Principles under-responsive action

Rapid response: Rapid response is one of the principles identified by this paper under this action. This is designed to provide rapid humanitarian assistance following conflict-related shocks and natural disasters resulting in population displacement, as well as with shocks ignited by return movements and in response to epidemics (UNICEF, 2018). Interventions must prioritize participation and leadership of women recognizing their role as the first 24-hour respondents to a humanitarian crisis. This principle should be guided by the three rapid response mechanism pillars including undertaking action between the first 48 hours and less than 30 days, prioritizing displaced women whose movement occurred within the last 3 months, and/or who can be reached in less than 3 months. Women in host communities and other vulnerable groups of residents living in areas of displacement or return need to also be prioritized. Despite the urgency that is needed, leadership and participation of women are needed as responders, monitors, and agents of change.13% of respondents interviewed revealed that rapid response is a key principle of a women-led humanitarian approach. All the respondents who indicated that rapid response is a key principle of women-led humanitarian approach are male. According to them, during a humanitarian crisis, women by virtue of their biological makeup and their roles as first 24-hour respondents need food and non-food items to take care of the family whilst the men are on the lookout to ensure the protection and safety of the family. All respondents with a household size above 8 see a rapid response as the only principle of women-led humanitarian approach due to their level of exposure during a humanitarian crisis where they are unable to feed themselves not to talk about their family. 66% of those who responded that rapid response is a key principle are above 55 years. For these respondents, lifesaving interventions should be prioritized immediately after a humanitarian crisis. Aside from providing crisis-affected people with hope, a rapid response will ensure that interventions needed to put a stop to the crisis are provided within the initial stages. This is the first stage of building resilience through meeting immediate and urgent needs.

Provision gender-responsive social services: Gender-responsive services are needed to put a stop to a crisis. The type of service and how it is delivered should be gender-sensitive and respond to the strategic needs of women. To bridge the humanitarian-development-peace nexus and achieve long-term solutions for people affected by the crisis, a comprehensive plan of action and efforts are needed from all stakeholders in both the humanitarian and development sectors (Oxfam, 2019). Women’s and girls’ access to reproductive health services is often interrupted in humanitarian crises. This exposes them to unwanted pregnancies in difficult conditions and increases the risk of unsafe abortions and maternal death. In the context of the women-led humanitarian approach, sexual and reproductive health services are urgently needed to save lives by addressing problems related to sexual and gender-based violence, unwanted pregnancies, obstetrical complications, and a multitude of reproductive complications (Government of Canada, 2019). Restrictions of movement during the initial stages of the COVID 19 pandemic put women and girls, and other marginalized groups, at greater risk of violence. Evidence and experience show that humanitarian emergencies magnify existing inequalities with specifically gendered impact, resulting in long-lasting and detrimental effects on gender equality and women’s rights, specifically around protection risks of women and girls, such as increase of GBV incidences (Government of Canada, 2019). The outbreak of COVID 19 also exposed women, adolescent girls, and children to additional agricultural and fieldwork and an increase in unpaid work responsibilities, increasing their risk of disease transmission. This also heightened the risk of engaging in prostitution to contribute to income for their families which in turn puts them at risk of sexual and physical violence. Under such circumstances, it is imperative to provide services to reduce the protection risk of women. The services should also be fit for purpose and be identified by women. Other services needed include mental and psychosocial support, medical assistance, economic assistance, and provision of both physical and invisible safe places. Only female respondents responded that the provision of gender-responsive social services is a key principle of the women-led humanitarian approach. This could indicate how less important this principle is, it is important to note in recent humanitarian response, there is increased consideration to provide services that respond to the strategic needs of women and girls affected by humanitarian crisis.

Principles under restorative action

Women as humanitarian actors and not just beneficiaries: Though women and girls are powerful agents of change in their communities, their contribution to the humanitarian decision-making process is often ignored. They are the owners of their needs and know how to communicate to reflect their inner worries and anxieties. In most cases, the uniqueness of the context and socio-cultural barriers women face are not considered in times of crisis (Government of Canada, 2019). Therefore, any women-led humanitarian approach should value the voices and the leadership of women and girls affected by the crisis in humanitarian interventions. 13% of respondents of those interviewed during the development of this paper indicated that women as humanitarian actors and not just as beneficiaries is a key principle of the women-led humanitarian approach. It is interesting to note that 66% of those who responded that women as humanitarian actors are a key principle of women-led humanitarian approach are male. All respondents with a diploma as their level of education see women as humanitarian actors as a key principle of the women-led humanitarian approach. These respondents are of the view that this principle facilitates processes that support and promotes women-led interventions that place and support women’s participation, leadership, and decision-making in humanitarian action at the centre.

Mobilization and organization of women

Mobilization and organization of women into groups based on location and interest is one way of restoring people’s dignity after they have suffered abuse. It serves as a springboard for targeting and supporting people living with the effects of trauma, violations, and stress. This principle is a critical pathway in the women-led humanitarian approach to create safe spaces and reduce exposure of the entire community to risk through the lens of the women-led humanitarian approach. Such initiatives have helped to position women in the forefront in humanitarian programming through the effective participation of women as both beneficiaries and agents of change. Working in a group gives women a sense of belongingness and empowers them to choose how to participate in decisions on how to meet their needs. The women-led humanitarian approach should aim at strengthening women’s participation and leadership in humanitarian actions. It should support the expertise and capacity of women leaders and local women’s organizations like the association of women IDPs, women platforms, women affected by the crisis, etc (CARE, 2012). Women groups collaborate with village heads, local authorities, and civil society to influence the local level humanitarian system to ensure the participation, leadership, and empowerment of women and girls in humanitarian processes. When women put themselves into groups, humanitarian actors prioritize their involvement to ensure that adequate and efficient services and assistance are provided, with attention to ”do no harm” and users’ safety, dignity, and equal access. About 14% of respondents within the ages of 35-55 gave an equal rating for all the principles including mobilization and organization of women as the key principle of women-led humanitarian approach. It is important to however note that respondents with household sizes between 1 to 3 responded that mobilization and organization of women is not an important principle of women-led humanitarian response. According to these respondents, mobilization and organization of women into groups further delays humanitarian. This is accentuated by the fact that humanitarians would prefer dealing with these groups as representatives of the communities affected by the crisis and thereby widening the gap between humanitarian organizations and individual community members affected by the crisis.

IMPLEMENTATION OF COMMUNITY GENERATED PLANS BY WOMEN: Any principle of a women-led humanitarian approach should support models and innovative approaches that eliminate barriers to women’s participation in community development actions. The principle should empower women and advance gender equality through humanitarian actions. 13% of respondents responded that the implementation of community-generated plans by women is a key principle of the women-led humanitarian approach. Of those who responded that implementation of community-generated plans by women is a key principle of women-led humanitarian approach, 66% are above the age of 55 years. Respondents with household size above 8 see this as the only principle for a women-led humanitarian approach. Respondents were of the view that this principle ensures that women lead in developing community protection and livelihood plans which reflects the immediate and strategic needs of the community. They appreciate and understand the uniqueness of each household and provide the needed support to these households to reduce their burden during a humanitarian crisis. Women-led community-generated plans ensure the integration of prevention and response measures for protection risk into various stages of community action to build resilience. A women-led community action plan would create awareness activities, including activities around positive masculinity to include men and boys. These plans demand actions from humanitarian actors including communities to strengthen community-based systems to prevent, mitigate and respond to protection risks including sexual and gender-based violence which is rampant during a humanitarian crisis.

PRINCIPLES UNDER BUILDING ENVIRONMENT ACTIONS

Shifting positions of women

A humanitarian crisis should be seen as an opportunity to shift the positions of women. This has the effect of addressing unequal gender relations thereby transforming or abolishing harmful gender norms. This principle stimulates deep-rooted changes in behaviour, values, attitudes by creating an enabling environment for the full respect of human rights (ICRC, 2008). This principle has to do with a long-term transformation that changes the position of women from mere recipients of humanitarian assistance to active agents of change. This principle works to change the structure of the social system by ensuring that gender equality considerations are integrated into the design, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation humanitarian approach (Bates and Peacock, 1987).

The women-led humanitarian approach aims at catalyzing change that shifts women’s disadvantaged position in social relations (Pacholok 2013). It builds women’s resilience by increasing their capacity to cope with hazards and stress. Women can resist, avoid, and cope with situations or conditions that stimulate vulnerability. Cutter et al. (2008) suggest that resilience is a trigger of social change. It facilitates the ability of the social system to adapt and change, and learn in response to a threat. 17% of respondents indicated that shifting positions of women is a key principle of women-led humanitarian approach. 50% of respondents with a diploma as their level of education revealed that shifting positions and conditions of women is an important principle of women-led humanitarian approach. They believe that the women-led humanitarian approach leverages on humanitarian crisis effect a transformative change in the social, political, and economic structure of the household and community.

Accountability to women

According to the UNHRC (2020), conflicts and disasters heighten the vulnerability of women and girls who are already burdened by wide-ranging discrimination. Insecurity and displacement are major drivers of sexual and gender-based violence. They also trigger other crimes and human rights violations including a child, early and forced marriages and denial of access to sexual and reproductive health services. Whilst COVID-19 generated additional hardships for women and girls, fear of reprisals due to lack of fallback mechanisms and support, and the stigma often associated with gender-based violations all prevent women and girls from seeking protection and essential services. In cases where accountability mechanism functions, they focus on a narrow conception of justice limited to the identification and punishment of perpetrators of crimes without consideration of establishing relevant institutions, structures, and policies to reduce or eradicate the continuum of human rights violations suffered by women and girls.

The women-led humanitarian approach promotes accountability for women and girls by providing adequate safeguards to protect them in humanitarian contexts. The approach increases accountability through inclusive processes that focus on the voices and needs of women and girls, with punitive actions and sanctions to address the consequences of the violations and to prevent further violations. Most respondents (30%) interviewed during the development of this paper responded that accountability to women is a key principle of the women-led humanitarian approach. This includes 86% of these female respondents and 50% of male respondents. The respondents argue that the approach emphasizes on-demand accountability from the state to uphold the dignity and rights of women and girls who have suffered, punish perpetrators, and institute mechanisms to prevent a recurrence. The approach ensures that government agencies that are not responsive to the needs of women are challenged to relook at their ways of operations. 71% of respondents who responded that accountability to women is a key principle of women-led humanitarian approach have a household size between 1 to 3. Also, 57% of respondents who responded that accountability is a key principle of women-led humanitarian approach are between the ages of 26-30.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Conclusions

The dichotomy between the feminist humanitarian approach and the women-led humanitarian approach has to do with how interventions are implemented from a feminist lens and how women’s leadership is promoted in humanitarian action.

Women play a critical role in providing care and the rebuilding of communities in the aftermath of a crisis. They are a critical resource during humanitarian response and must contribute to make the decisions that affect them and their families.

70% of respondents revealed that the women-led humanitarian approach is the humanitarian approach that empowers women and girls as change agents and leaders. 62.5% of these respondents are female. Of those who responded that the women-led humanitarian approach empowers women and girls as change agents and leaders, about 43% fall within the ages of 26 to 30 years. 31% fall with the ages of 31 to 55 whilst 26% are above 55 years of age.

About 9% of respondents responded that the women-led humanitarian approach is the humanitarian approach that protects, respects, promotes, and fulfils women’s rights whilst about 9% responded that the women-led humanitarian approach is the humanitarian approach that delivers gender-responsive services.

The women-led humanitarian approach should be guided by principles that seek to reduce vulnerabilities and increase resilience through responsive, restorative, and building environment actions.

The two principles under building environment actions namely shifting positions of women and accountability to women are the most important principles of the women-led humanitarian approach. A total of 47% of respondents revealed that these two are most important as compared to 53% of respondents for the other principles.

All respondents with a household size above 8 see a rapid response as the only principle of women-led humanitarian approach due to their level of exposure during a humanitarian crisis where they are unable to feed themselves not to talk about their family. 66% of those who responded that rapid response is a key principle are above 55 years.

Recommendations

A women-led humanitarian approach should prioritize program interventions and processes that empower women as leaders and agents of change. The approach should create safe and secured spaces for women to lead in humanitarian response and recovery at the household, community and territorial levels.

Donors, INGOs, and other humanitarian actors should collaborate with the government to focus interventions on actions that build the environment by establishing and resourcing institutions to respect, promote and fulfil the rights of people affected by humanitarian crises. 47% of respondents interviewed revealed that the principles under building environment are the most important principles of women-led humanitarian approach.

To ensure transformative outcomes of interventions, it is important to align specific principles of the women-led humanitarian approach to specific actions outlined in the egg model. This will ensure consistency and program coherence in humanitarian interventions.

Government should develop a policy framework to practically support and eliminate barriers and obstacles that affect women’s participation in humanitarian and community development actions.

Author: Yakubu Mohammed Saani

References

Bates, F. and Peacock, W. G. (1987). Disasters and Social Change. The Sociology of Disasters.

OAKTrust.

Care International (2020). WHERE ARE THE WOMEN? The Conspicuous Absence of Women

in COVID-19 Response Teams and Plans, and Why We Need Them. Care International

Care International (2019). Women’s and girls’ rights and agency in humanitarian action: A life-saving priority. Care International

Care International (2017). Gender in Emergencies -She is a humanitarian. Women’s participation

in humanitarian action drawing on global trends and evidence from Jordan and the Philippines. Care International

Care International (2012) CARE International Humanitarian and Emergency Strategy 2013-2020

(p.4))- Care International

Colquitt, J.A., and Zapata-Phelan, C.P. (2007). Trends in theory building and theory testing: A

five-decade study of the Academy of management journal. Academy of Management

Journal, 50(6), 1281–1303.

Cutter, S. l., Barnes, l., Berry, M., Burton, C., Evans, E., Tate, E. and Webb, J. (2008b). A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters. Global Environmental Change, 18, 598-606.

Eric, N. and Thomas, P. (2007). The gendered Nature of Natural Disasters: The

Impact of Catastrophic Events on the Gender Gap in Life Expectancy. Association of

American Geographers, 97 (3). pp. 551-566. DOI: 10.1111

Government of Canada (2020). A Feminist Approach: Gender Equality in Humanitarian Action.

Government of Canada

Government of Canada (2019). Action Area Policy: Human Dignity (Health and Nutrition,

Education, Gender-Responsive Humanitarian Action). Government of Canada

ICRC (2008). Protection policy. Institutional Policy. ICRC

OCHA (2016). World Humanitarian Summit. UN

Oxfam (2019). The humanitarian-development-peace nexus. What does it mean for multi mandated organizations. Oxfam.

Pacholok, S. (2013). Into the Fire: Disaster and the Remaking of Gender. University of Toronto.

Sonya, R. (2019). Why ActionAid promotes women’s leadership in emergencies. ActionAid.

Susanne, J. (2008). Linking Livelihoods and Protection: A Preliminary Analysis Based on a

Review of the Literature and Agency Practice. University of London.

UN Women (2020). Guidance Note. How to promote a gender-responsive participation

revolution in humanitarian settings. UN Women

UN Women (2020). How to promote gender-responsive localization in humanitarian action.

Guidance Note. UN Women.

UN Women (2015). Europe and Central Asia. UN Women

UNFPA (2013). Annual Report: Realizing the Potential. UNITED NATIONS POPULATI

ON FUND, New York. 60p.

UNICEF (2018). Rapid Response Mechanism: Central African Republic. UNICEF

UNICEF (2012). Evaluation de la prise en charge de la malnutrition aiguë -République

Démocratique du Congo. Rapport de Mission. UNICEF Bureau Régional del’Afrique de l’Ouest et du Centre. 53p.

United Nations Human Rights Council (2020). accountability for women and girls in

humanitarian settings. UN.

WHO (2011). Gender, climate change and health. Draft discussion paper. WHO