The Oil Economy and Nigeria’s Involvement

This paper looks at the world oil economy in terms of what makes up the oil industry build-up. Beginning from oil field prospecting, exploration, developing, refining, marketing, and distribution; the developmental stages from crude extraction to refining and the formation of the oil economy. The Nigerian involvement in the oil industry was examined through the operations of the Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) as the eye and arms of the government. It is sad to note that, despite this endowment of this natural resource that could have turned Nigeria around to be a successful economy with unlimited fortune as a result of the hitherto successful agricultural nation before the independence, the country is set aback with different forms of foreign loans to fund basic economic projects as a result of official ineptitude, mismanagement, and inefficiency.

Introduction

Fundamental Brief on the Global Oil Economy

The development of petroleum business world over is hanged around crude oil prospecting through the sequence of exploration, developing, extraction, refining, shipping, marketing, and distributing of the oil products. Among the several finished products from the refinery are Fuel oil and Petrol make up the biggest chunk of the industry products. Petroleum oil serves as raw material input to several other products from the chemical and allied industry which includes, pharmaceuticals, solvents, pesticides, fertilizers, and plastics. (http://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/about-bp/what-we-do/finding-oil-and-gas.html – retrieved, 9/05/2016)

Literature Review

The Importance of Oil In the scheme of the World Consumption and Manufacturing Needs

It is hardly possible for petroleum oil to become fallow when other uses of petroleum oil are considered apart from the current major need for gasoline to propel combustible engines for transportation and others. This basic petroleum oil serves as very important raw material contents for the production of many other manufacturers without which many manufacturing industries will be grounded and put the world economy in jeopardy.

So, the emergence of the debate on alternative sources of energy, such as renewable energy to replace the relevance of fossil fuel especially, the introduction of electric cars could shake the need for petroleum energy to its foundation would hold no water. It is believed that fossil fuel producers should not be panicking in terms of the demands for their output if alternative energy resources are completely put in place and adopted. The continuing demand for petroleum products will remain as many of the world’s manufacturing industries will still need them for their operational existence.

According to Amponsah and Opei (2017), the global needs for fossil oil are unquestionable as the oil and gas industry is “one of the biggest world industries with enormous technological complexities that humanity could not afford to miss as essentials in our daily needs. Be it heating, transportation, lubricants, and various chemical, pharmaceutical, and petrochemical products are all inherent. They went ahead to acknowledge further that, 30billion barrels of oil are consumed worldwide every year“ (Amponsah and Opei, 2017).

Amponsah and Opei (2017), in (Gruenspecht, 2011) later acknowledged that the Energy Information Administration (EIA) in 2011 in the US projected that the world energy consumption would hit an increase of 53% from 2011 – 2035. It is also posited that Europe and Asia’s energy needs when put together, oil takes 32%, and in the Middle East alone, 53% is estimated; while the South and Central America, will take 44% and the consumption of North America is projected to be 40%. In the case of Africa, 41% usage is estimated (Amponsah and Opei, 2017).

Defining the organizations and individuals in the business of refined petroleum products transactions, Business Wires (2019), pointed out that refined petroleum products from crude oil such as gasoline, diesel fuel, naphtha, to liquefied petroleum gas form the nucleus of the refined products manufacturing market.

The Asia Pacific is equally mentioned as the largest operator in this identified market and they are in charge of 27% of the world oil manufacturing marketing operators in the year 2018. This is followed by North America contributing 24%, emerging as the number two biggest. The lowest contributor is judged to be the African region but not scored in terms of specific figures according to Business Wire (2019) and the reason for this non-specific figure attachment could not be readily stated.

Due to advancements in technology, there is a conscious transformation into gas-liquid petroleum with the needed technology adopted to make it viable for transportation fuels and the by-products being used in the production of many other products such as plastic wares, cosmetics, and detergent items. The product is attested, to be of high-quality gauge spear-headed by giant oil companies such as Shell, Chevron, and PetroSA who have invested heavily in the process.

The process is also posited to avail users of the purest fossil fuel that is abundant and less costly.

The latest process allows natural gas to replace crude oil and is also capable of extracting high-quality transportation fuels, and other by-products for the production of plastic, body cream, and detergent products according to Business Wire (2018). Whenever the process is fully harnessed, it may be capable of displacing crude fossil fuels.

Venezuela is judged to possess the world’s largest oil deposit in the tune of a proven reserve of 300,878 million barrels. Saudi Arabia tails this trend as the second largest with a proven reserve of 266,455 million barrels. Below is the tabulation of oil deposits regarding specific nations that are naturally endowed as collated by Jessica Dillinger (2019).

Table 1:Showing Oil Deposit in the Various Oil-Rich Nations in Millions of Barrels

| Rank | Country | Reserves (millions of barrels), 2017 US EIA |

| 1 | Venezuela | 300,878 |

| 2 | Saudi Arabia | 266,455 |

| 3 | Canada | 169,709 |

| 4 | Iran | 158,400 |

| 5 | Iraq | 142,503 |

| 6 | Kuwait | 101,500 |

| 7 | United Arab Emirates | 97,800 |

| 8 | Russia | 80,000 |

| 9 | Libya | 48,363 |

| 10 | United States | 39,230 |

| 11 | Nigeria | 37,062 |

| 12 | Kazakhstan | 30,000 |

| 13 | China | 25,620 |

| 14 | Qatar | 25,244 |

| 15 | Brazil | 12,999 |

| 16 | Algeria | 12,200 |

| 17 | Angola | 8,273 |

| 18 | Ecuador | 8,273 |

| 19 | Mexico | 7,640 |

| 20 | Azerbaijan | 7,000 |

This update is researched by Jessica Dillinger and made available around January 2019.

Operationally, the oil industry sector normally takes the form of three main divisions following the line of upstream, midstream, and downstream. But in the case of Nigeria, there is no clear cut distinction between the midstream and the downstream operations as Petroleum Products Marketing Company (PPMC), an arm of Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation (NNPC) is in charge of both streams (Onigbinde, 2014)

An Insight into Nigeria’s Oil and Gas Business and Marketing

Ibe et al. (2015), Idemudia and Ite (2006) in their different research papers concluded that the advent of the business of marketing and distribution of petroleum fuel and lubricants in Nigeria were pioneered by five international oil marketing companies and later joined by three other oil marketing companies that were indigenous in structure.

Amongst the foreign companies were Elf, Agip, Exxon Mobil, Total, and Texaco and the three national (indigenous) companies are were African Petroleum (former BP) with NNPC holding 40% of its own; National Oil with NNPC holding 40% of its share capital; Shell capitalizing on 40% ownership – living 20% for private Nigerian participation; and Unipetrol Nigeria Plc with 40% of equity for NNPC (Onigbinde, 2014; Ehinomen and Adeleke, 2013; Bradiq, 2013; Akpogbommeh and Badejo, 2006).

Above 750 independent oil marketers scattered all over Nigeria are also licensed to participate in petroleum products distribution Bankole (2020).

The activities of the three domestic oil and gas companies equal 30% share of the whole oil and gas market. When excluding the independent marketer’s operations the three domestic companies enjoy a 45% share of the total market.

With General Oil leading the independent marketers in the distribution of Oil and Gas, They collectively enjoy about 36% share of the market.

With NNPC having its hands virtually in all of the refined products, even if it is not physically involved before setting up its distribution mega stations.

At this juncture, viewing the settings of oil distribution players in Nigeria, if any distribution failure occurs the blame is substantially placed on foreign distribution companies instead of NNPC, which dominates the strategic distribution control as it controls substantial shares in all the public quoted marketing companies (Onigbinde, 2014; Ehinomen and Adeleke, 2013; Bradiq, 2013; Akpogbommeh and Badejo, 2006). As the ultimate distribution and supervisory authority are vested in the hands of NNPC, it behooves the institution to address all forms of distribution inadequacies. NNPC should therefore be held accountable for any lapses of distribution failure.

Moreover, since the independent marketers are in charge of 36% market share and the three indigenous main marketers are in charge of 30% of the total market, this means that not less than 66% of products distribution is covered by domestic marketers put together. This should be adequate to provide a balanced local distribution without any crisis.

However, this argument cannot be taken as a defense to ascertain the culpability of the foreign marketing companies because some of the major participants in these foreign major marketing companies are also Nigerians. It is therefore assumed that some of the distribution ineffectiveness could be apportioned to these international distribution companies and the usual unorthodox business practices in Nigeria.

The National Wealth

The major composition of Nigeria’s, the commonwealth is composed of revenue from oil income. Most national, state, and local government developmental, projects are funded through the federal government’s federation account nts which in turn depended heavily on oil revenue (Ross 2003). The Nigerian economy is therefore essentially an “oil economy“ (Eko et.al 2013). Until recently, NNPC has had no direct involvement in the marketing and distribution of refined products as seen before, but its engagement in the ownership of almost all the marketing companies’ equity shares exposes its participation in this downstream oil subsector operations.

Nigeria’s economy is endowed by 28% of Africa’s confirmed oil deposits. This makes it the second-largest oil endowment in the continent with Libya the largest, having 48,363 million barrels (Dillinger, 2019). Nigeria is the forerunner crude oil producer in the continent of Africa with an average output in 2010 amounting to 2.4 million BPD. Meaning 24% of total Africa’s production for that year (Siddig et al, 2014a; Siddiq et al, 2014b; Soile et al, 2014). With the existence of four public own refineries, the corporation (NNPC) could not prove its effectiveness and efficiency to manage the refineries but to import a very substantial volume of the country’s refined oil needs, not to even talk of exporting excess refined products to neighboring West African countries. Though this problem is largely perpetrated by NNPC itself, it has been unacceptably concluded to be largely due to the “sharp” business practices of Nigerian businessmen and notable government officials now dubbed “economic saboteurs”.

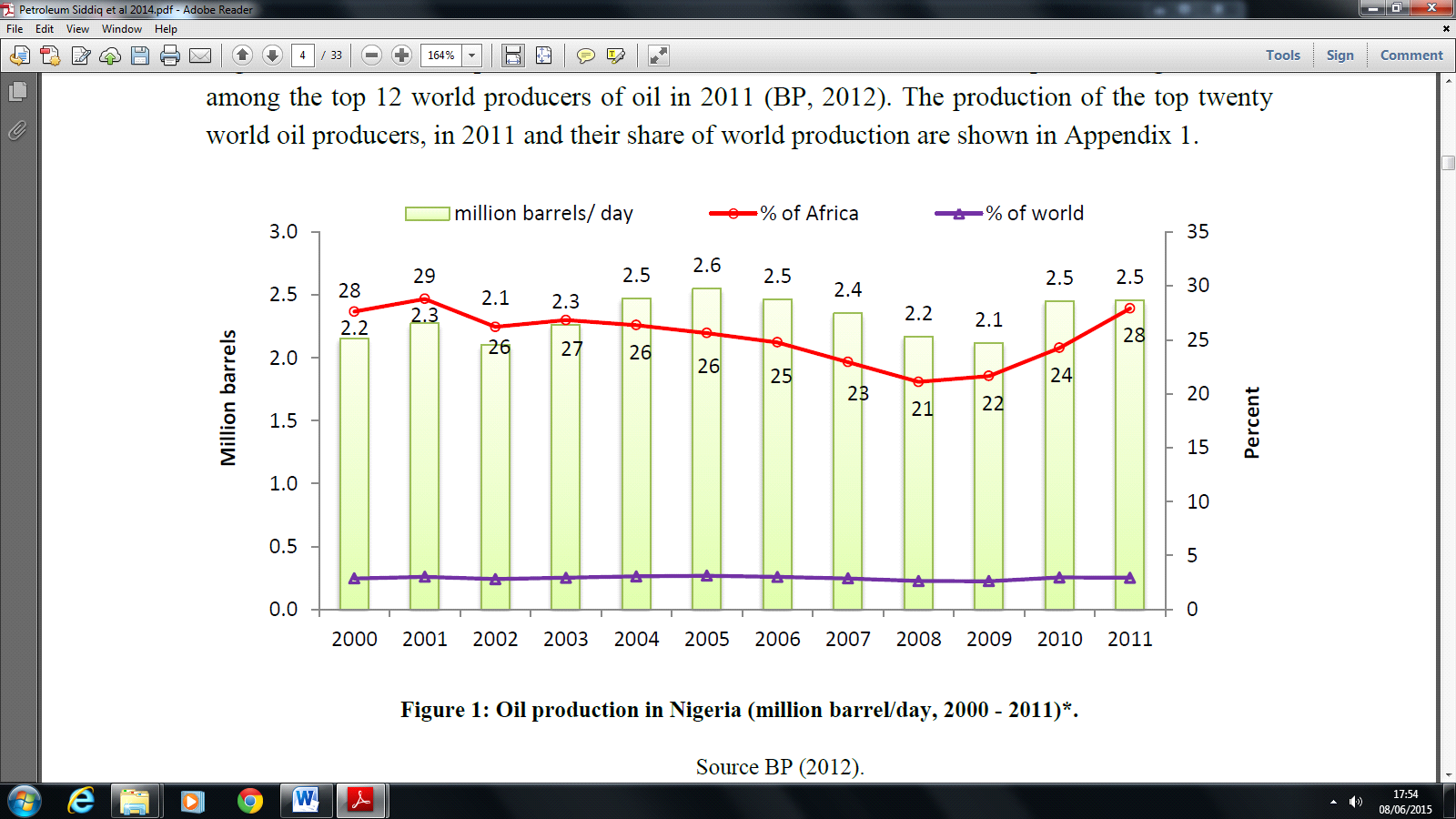

Figure 1: Shows the Officially Claimed Production & Distribution of OIL in Nigeria from Year 2,000 -The year 2011

Source: BP (2012). Curled from Siddig et al (2014), “Impact of removing refined oil import subsidies in Nigeria on poverty”. The right vertical axis measures the shares while the oil production index is measured by the left vertical axis.

Figure 1: The graph above, explains Nigeria’s crude oil production operations between 2000 and 2011, twelve years in a row. This figure shows that Nigeria’s lowest production volumes were in 2002 and 2009 figuring 2.1 million bpd in a period of 12years captured in succession. The year 2005 shows the highest bumper production of 2.6 million bpd. (This is shown by the left side vertical axis). The red dotted line shows Nigeria’s output within the frame of total Africa’s output. This ranges between 21% and 29% share of total Africa’s production output. Its share of the world’s output almost consistently remains below 3% within the period reported.

According to the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), Nigeria’s production per day is falling (in comparison with the data shown in -Figure 1) as the reported data of June 2019 is said to be 1.855 million bpd. This is an improvement against 1.726 million bpd achieved in May 2019. When calculated on an average basis, from January 2002 to June 2019 recorded data shows 1,959.500 barrels per day (http://www.ceicdata.com>indicator – Retrieved, 08/08/2019).

So far, Nigeria’s ever highest crude production per day was 2,496.000 barrels done in November 2005 and the least in recent dispensation is 1,419.000 bpd in August 2016 (http://www.ceicdata.com>indicator – Retrieved 08/08/2019). The fall in recent production output could be the direct effect of the incremental decline in world crude oil prices far back as 2014 caused by periodic volatility in crude oil marketing.

The attacks suffered on Saturday, 14/09/2019 by the Saudi Arabia crude processing plant that accounted for 5% of the world’s supply could be said to be responsible for a seemingly slight jerk-up price in the world market. This led to a global oil price increase during the period of incidence. (London Evening Standard, 17th Sep. 2019).

According to Metro, a daily London-based newspaper of Tuesday, September 17, 2019; the attacks had raised the World oil prices by 20% as of 19th Sep. 2019 (Monday) only to be reduced by US reserve release.

Despite the total installed refining capacity of 445,000 bpd, for Nigeria’s four refineries – Port Harcourt “A” and “B”, Kaduna and Warri – they could not save Nigeria from importing refined products because of very low capacity utilization of NNPC operations (Soile et al. 2014). Very sad that this refinery could not function well to produce even half of the country’s daily needs due to inefficient operation and poor planning and management. This made NNPC, through its marketing arm (PPMC) resort to importing 85% of Nigeria’s local requirement in 2009/2010 and local refineries taking care of just 15% of the country’s needs (Siddig et al. 2014a; Rice, 2012). As usual, NNPC has its ways of defending its obvious weaknesses as the failure was confined to the devastating activities of vandalism crude transportation facilities, such as the pipelines and effect of corruption within the system; poor factory maintenance tradition, and above all smuggling and theft activities of bunkers and sea pirates (Christopher and Adepoju, 2012; Saddiq et al, 2014a; Business day, 2013).

It is even being pessimistic about that, given a situation whereby all ‘things being equal, and with full running’s of the four refining factories, there is no way that they could have achieved the full domestic need as experts opined that only 63% of the nations aggregate consumption need could be met (Siddig et al, 2014a and b).

What then could be the solution? This probably could have been a provision for expanding the installed capacity for the four refineries or embarking on building additional one(s). Otherwise, private refinery investors could be licensed to take a stake in building private refineries, maybe on joint venture provisions.

The Petroleum Subsidy Scams

One would think that prices are the problem of petroleum products distribution in Nigeria; the Nigerian Government had resolved to subsidize the outrageous landing cost of some imported petroleum products to cushion the effect on consumers buying strength. But alas, the intention of the federal government to save the situation resulted in some unscrupulous petroleum product marketers inflicting further difficulties to both the consumers and the federal government itself as the gesture became a notorious opportunity to corrupt the officials and the importing agents for the products which blossom their illegal revenue base (Siddiq et. al, 2014; The Economist, 2011).

Other corrupt dimensions include paving the un-usual ways of unprecedented sharp practices on the part of unscrupulous petroleum marketers who, were saddled with the contracts of importing the refined petroleum items; dubious activities of the local bulk and retail merchants; as well as smuggling of exorbitantly subsidized petroleum products became a jamboree, criminally crossing the national borders with the government-subsidized products to make illegal supernormal profits in the neighboring countries (The BBC, 2012a)

According to The BBC (2012) in Bankole (2020) “Nigerian Government-subsidized 59 million liters of fuel per day in 2011, the daily consumption estimate for domestic use was 39 million liters – where then is the difference of 20 million liters placed?” This revelation is weighty enough to describe how petroleum officials and their petroleum merchants and contractors are callous in inflicting further hardships to the government of Nigeria, its citizenry, and petroleum consumers. The government had done its bit, by releasing money for 59 million liters over 20 million liters but yet consumers continue to queue endlessly in the nation’s petrol stations and sometimes some of them sleep overnight in these stations to avoid missing out of the queue when they are close to reaching their turns. At times, military men and other security agencies could run crazy scattering them to create a state of pandemonium. This again sometimes led to scuffles between the security agencies personnel and eager customers, or between the customers, when some are trying to jump the queue to avoid long waiting time because not enough petroleum products shall be released for sale to consumers so that they could be able to perpetuate their corrupt hoarding motives. Many blames have been apportioned to several players along the distribution chain but there is no strong evidence to show a situation of channel ineffectiveness or inefficiency but rather the nature of sharp practices prevailing amongst all the distribution channel members right from the staff of NNPC in charge to the various marketers and contractors along the distribution chain (Siddig et al, 2014; The Economist, 2011; and BBC, 2012a).

The Effect of Excessive Dependence on Petroleum Economy

Agriculture was the dominant economic activity before the emergence of the nation’s petroleum economy due to the discovery of petroleum crude oil in large quantities in 1956. This was even slightly before the nation’s political independence from the British colonialist. Even shortly after independence, Nigeria still relied on its agriculture to propel its economic wellbeing (Onigbinde, 2014; Ango-Abdullahi, 2002). The activities of the ancient Agricultural and Commodity Marketing Boards at the time created several development projects in all the regions of the country which made governments provide different forms of different business infrastructural foundations that help to spring-up industrial and commercial estates to aid the taking off of both internal and external businesses funded by money generated from the proceeds of agricultural activities as aided by the agricultural marketing boards (Ango-Abdullahi, 2002).

The Displacement of Agriculture and Enthronement of Oil Economy

This era of agricultural empowerment was however not allowed to live long as a relatively cheaper means of government earnings surfaced through the emergence of oil discovery, exploration, and development. Thus big-time oil marketing activities was much focussed on at the detriment of agriculture as soon as the petroleum oil business sprang up in the middle of the 1950s spanning through the orchestrated period of the 1970 oil boom scenario (Onigbinde, 2014)

The overnight rise in the wealth of Nigeria nation through oil exploration and marketing and exporting, completely blocked the nation’s foresight to carry along with the prospect recorded in agriculture along with the newly found treasure of oil business. Less emphasis was placed on agricultural marketing and development in favor of over-concentration and dependence on oil development and marketing. So the expansion of the agricultural marketing base was slowed down and later got to a halt and stagnant position in the scheme of the nation’s business and general economic development.

It is virtually needless to say the advent of the oil economy in Nigeria subjugated the development of the erstwhile already nationally developed Agricultural Sector. The agric sector that used to be the cash cow of the nation’s economy was neglected and its contribution of about 48.23% in 1971 to the nation’s national income nose-dived to 21% by 1977(Onigbinde, 2014). The contribution of foreign trade in agricultural products which contributed 20% to the total export in 1971 sadly slides to 5.71 in 1977 according to Onigbinde (2014); Ajakaye and Akinbunmi (2000) and Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN), (1994). Thus this awareness announced the gradual shift of the nation’s economic dependency from an agricultural-led economy to an economic dependency on oil-led. By this period, oil had contributed close to 90% of national income on international business that generates foreign exchange while contributing about 85% of the total national export. The drastic drop in agricultural production and its export contribution to the country’s GDP from 48% to 21% between1971 – 1977 and the export contribution of agricultural produce to total national export from 20.7% in 1971 to 5.71% in 1977 simply indicates total neglect of this sector.

The downward trend in agricultural products cultivation can be said to bring about the same response, but in a reversed situation that the immediate rise in the federation balance sheet as a result of oil mining and marketing activities since the 1970s. According to Adebanjo (2015), In the days before the sudden rise of Nigeria’s oil prospect the country derived its foreign income through its ventures in palm kennel/oil from the east; Cocoa in the West; and groundnut in the North locations of the nation. Nigeria that led the world in cocoa production in the past had its output fallen by 43% within the years of 1972 and 1983. Such important cash crops like rubber had their output also fallen by 29%, groundnut by 64%, and cotton by 65% around the periods stated above.

The Oil Boom Effect on Other Agric Production

It is important to note that the devastating effect of the oil boom era does not stop in the production and marketing of cash crops alone as a similar fate befell on the national food crops productions. It was partly because of the damages done on agricultural production in general that the National Peoples’ Party of Nigeria (NPN) government led by President SheuShagari launched in 1980 the erstwhile infamous policy of pioneering the importation of basic foods to the country draining the country’s foreign reserves despite Nigeria being a leading agricultural economy in the past and self-sustaining in agricultural productions. The policy not only instituted a large dimension of international official corruption in the polity but it was also asserted by Prof WoleShoyinka (a Nigerian social critic and Nobel Laurel) in his self-analysis that, it duped Nigeria of the substantial and unbelievable sum of several billions of dollars. It is now dawn on Nigeria that agriculture has been marginalized and not worth participation by heavy investors and professionally qualified experts as seasoned agricultural graduates had moved into purely commercial, industrial, and customs offices to “practice”, due to unchecked and over-dependent on the oil economy.

The Nigerian Oil Wealth and its Impact on Democracy

According to Ross (2003), Nigeria’s oil wealth had also dealt a dangerous blow on governance as democracy suffered an unequaled setback in the practice of democracy. He argued that the fall of the manufacturing industry sector in Nigeria could not be exonerated from the over-dependency on the petroleum sector to over spearheading the economic development of the Country.

Advancing his reasons, Ross (2003) in Bankole (2020) postulated that “industrialization is the bedrock of democracy given its power to build and develop an elitist middle class within the urban society capable of establishing strong and formidable democratic structures and institutions.” As a result of this and according to Ross (2003) the oil economy has subverted democracy, which has been overthrown by the oil economy as a result of neglect accorded manufacturing sector that is an important economic area that could boost a fledgling democracy to thrive.

An environment without a vibrant middle class will be liable to erode the fundamental culture and economic growth. According to Ross the petroleum sector predominantly focuses on the recruitment of highly skilled labor that is normally more than the middle-class standards (Ross, 2003).

Nigeria and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)

OPEC is a petroleum producer’s cartel, established to control the global crude petroleum sales to better a lot of member nations. Nigeria was admitted into the cartel in 1971. This was due to its huge earnings in crude oil export by the 1970s. As a result of joining the OPEC, and as a mark of national business identity, the Federal Government of Nigeria incorporated the relevant organization known as “Nigerian National Oil Company – NNOC (Onigbinde, 2014). Later in 1977, the corporation was re-christened “Nigerian National Petroleum Corporation” (NNPC), the name it bears up till today.

NNPC as a corporate body now acts as the supervisor and manager responsible for the upstream and downstream operations of the Nigerian national oil industry, accountable to the Government of Nigeria (Onigbinde, 2014; Idemudia and Ite, 2006; Olorunlambe, 2004). As part of its terms of operations, NNPC is mandated to act as the representative of the federal government in all Joint Ventures Agreements with Multinational Oil Companies (MOC) and other venturing bodies, including their licensing for operations in Nigeria. Nationally, NNPC is saddled with the responsibility of distributing refined petroleum products into all parts of the country at uniform prices irrespective of distance and logistic requirements including all other unforeseen circumstances.

Suggestions for Future Research in Nigeria’s Oil Economy

At this juncture, the author will admonish the Federal Government of Nigeria to put in place a reliable implementation of economic research that will look into the possibility of Nigerian nation rising again if given the chances of another oil boom which is rare to come by as the world is embracing the call for abandoning the use of fossil fuel in cars for electric substitute – as one of the greenhouse measures to battle the effect of climate change which is seen as a direct impact of global warming.

It is high time for Nigeria to research into the resuscitating of the country’s agric economy and raises back the previous fortune of the manufacturing sector that is now totally collapsing as a result of capital flight.

According to Ross (2003)and Bankole (2020)“industrialization is the bedrock of democracy given its power to build and develop an elitist middle class within the urban society capable of establishing strong and formidable democratic structures and institutions.” This is one of the most essential needs of Nigeria to save her from the various cries for disintegration.

Methodology

The researcher employed both primary and secondary research methods in gathering research information. These include the use of materials from the government and its agency’s sources/ corporations. Primary sources include research surveys and the secondary sources include a review of relevant textbooks, research articles, published journals, and relevant official reports.

Data Analysis

This section of this research journal publication is in charge of questionnaire responses while administering the short research survey. Email platform was used to get in touch with randomly selected research respondents. The general Nigerian public that includes civil servants, artisans, and professionals across the country was surveyed.

The use of percentages was prominently employed in the analysis to conclude in regards to data collected because of its users without any ambiguity research on research outcome and inferences (Aaker, D. et.al, 2003), 85 pieces of questionnaire materials were distributed to respondents via emails. Out of this, 60 were returned after completion.

Table 1: Nigeria’s oil economy is a curse when compared with similar economies around the world, e.g. Saudi Arabia, UAE, etc.

| Decision | No. of Respondent (60) | Percentage (%) |

| Yes | 20 | 33.3% |

| No | 40 | 66.7% |

| Total | 60 | 100% |

Source: Email Questionnaire Administration, 2021

The above table reveals that 33.3% of respondents amongst the 60% of respondents agree that the endowment of the oil economy to Nigeria is a curse, while 66.7% admitted that it is not a curse to the country to have been endowed with an oil economy.

Table 2: The Nigerian Oil dependency “killed” its agricultural economic success of the past and subdued its industrial development.

| Decision | No. of Respondent (60) | Percentage (%) |

| Yes | 60 | 100% |

| No | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 60 | 100% |

Source: Email Questionnaire Administration, 2021

As revealed in table 2above, a whopping 100% admit that the oil dependency of Nigeria “killed” its agricultural economic success of the past and subdued its industrial development, while 0% of respondents disagree with the notion.

Table 3: Do you agree that NPC needs its operational structures, especially in the areas of accountability and honesty of purpose on the part of the corporation is reformed?

| Decision | No. of Respondents (60) | Percentage (%) |

| Yes | 60 | 100% |

| No | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 60 | 100% |

Source: Email Questionnaire Administration, 2021

In table 3 above, 100% of the respondents agree that NNPC needs its operational structures; especially in the areas of accountability and honesty of purpose on the part of the corporation be reformed. On the contrary, 0% of the survey respondents disagree.

Table 4: Is the global downward demand for fossil fuel, a challenge to Nigeria’s oil economy given the fact that heating, transportation, lubricants, and the various chemical and pharmaceutical products’ demands are all inherent?

| Decision | No. of Respondent (60) | Percentage (%) |

| Yes | 36 | 60% |

| No | 24 | 40% |

| Total | 60 | 100% |

Email Questionnaire Administration, 2021

In table 4 above, 60% of the respondents believe that the global downward demand for fossil fuel is a challenge to Nigeria’s oil economy given the fact that heating, transportation, lubricants, and the various chemical and pharmaceutical products’ demands are all inherent. But on the contrary, 40% of the respondents did not have this belief of any challenge to Nigeria’s oil economy given the fact that heating, transportation, lubricants, and the various chemical and pharmaceutical products’ demands are all inherent.

Table 5: NNPC has been largely criticized for inefficiency and ineffectiveness in its general and some specific operations, the corporation in turn shifted the blame on “sharp” business practices of the Nigerian Business environment notably, government officials and doggy businessmen now dubbed “economic saboteurs”. Who exactly is to blame?

| Decision | No. of Respondent | Percentage (%) |

| NNPC | 60 | 100% |

| Business environment | 0 | 0% |

| Government Officials | 0 | 0% |

| Oil Businessmen | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 60 | 100% |

Email Questionnaire Administration, 2021

In table 5 above, the question that NPC has been largely criticized for inefficiency and ineffectiveness in its general and some specific operations, in which the corporation, in turn, shifted the blame on “sharp” business practices of the Nigerian business environment notably, government officials and doggy businessmen now dubbed “economic saboteurs”, a total of 100% of respondent in the survey agree that NNPC is to blame. None of these respondents supported the view of NNPC on this as can be seen that 0% supported the NNPC claim of the Nigerian business environment, government officials, nor oil businessmen.

Results and Discussions

The Nigerian oil economy is supposed to be a thing of joy that could have brought general success to all other aspects of Nigeria’s economic environment. What this research has revealed so far is, however, did not call for any form of celebration(s). For example, the result of the table 1 exercise reveals that it is a misnomer for Nigeria to have been endowed by this “gold”, the black gold as called in some quarters – that is petroleum oil. This means Nigeria’s economy would have performed better under some other form of resource(s). The recklessness by which the economic managers run this affair portrays a disaster. This is supported in the literature by Ross (2003) who opined that “Nigeria’s oil wealth had also dealt a dangerous blow on governance as democracy suffered an unequaled setback in the practice of democracy” in the land. This simply means that the disaster is not only on the economy but also spread to the handling of democracy in Nigeria’s governance. This is evident in the way Nigerian politicians and past military rulers wastefully handled the flow of money generated from the sales of oil. This empirical research does equally prove so, as 66.7% of respondents assert that “Nigeria’s oil economy is a curse when compared with similar economies around the world, e.g. Saudi Arabia, UAE, etc.” 33.3% respondents’ minority, however, think Nigeria is “moving forward”.

This research also suggests that the failure for not manage Nigeria’s oil economy well enough resulted in dismantling the previously recorded agricultural success and even the industrial foundation as laid down by the hitherto agricultural success. This view is also supported by Ross (2003) in the literature as reviewed and empirically supported by 100% of this research respondent.

From this research, it could be asserted that NNPC needs its operational structures to be fully restructured. This is evident by the 100% response of NNPC’s lack of accountability and honesty of purpose in many of its operational structures. This is simply unacceptable by all known standards, be it local or international. The literature is equally not silent on this as voiced inter alia, “corruption rate is abnormally great” as observed by Gylfason (2001”; Sachs and Warner (1999); Leite and Weidermann (1999).

Though it is generally agreed that, fossil fuel usage does not end in the combustion of oil to propel motor engines and generate lightings. It exists for many other usages to support meaningful human existence as revealed by the literature. The fact that the whole world is heading for a greenhouse revolution as a result of global warming; is a sign to show that the era of easy money through fossil fuel sales is weaning. All oil dependant nations must therefore buckle up for the rainy day! Though 60% of the research respondents feel that the downward trend in the world demand for fossil fuel will not adversely affect Nigeria’s oil economy, many research attempts are in support of synthetic alternatives of oil as raw materials for the productions of other human necessity goods as postulated by Amponsah and Opei (2017). The 40% respondents view in this reach, that it is not of any challenge to Nigeria’s oil economy “given the fact that heating, transportation, lubricants, and the various chemical and pharmaceutical products’ demands are all inherent” cannot be easily thrown overboard. Their views must equally be respected and honored.

In table 5, the response of 100% of the research respondents against NNPC’s ‘blame’ is very amazing and overwhelming. NNPC has no choice (given the fact that this research is primary and not an omnibus) than to admit this blame of inefficiency and infectiveness in its operations, given the fact that NNPC, as a government corporation with all enabling statutory powers can not ‘fly above board’ and this empirical research has spoken so loudly and too.

Research Implications

This research has so far established several bottlenecks in the development of Nigeria’s oil economy. It is a matter for Nigeria over the years “taking a step forward yesterday, and ten steps backward today”.

This research implies that to save the economy from a total collapse, there must be an urgent economic diversification program from the root to the topmost economic planners and executors – from local government levels – to the state government – and the federal government. These are the primary and direct beneficiaries of the proceeds of the oil economy and are the ones sharing the oil revenues. Various grass-root entrepreneurs, from agric to manufacturing and services must participate actively, with the various levels of government creating the enabling environments.

The economy must fully embrace the revival of agricultural and manufacturing industries and the role of the banking industry must urgently be geared towards the agricultural and manufacturing industry to bring back employment in these areas. This will once again empower the middle class to take control of the country’s political economy as today Nigeria is politically and economically endangered, dangerously putting the country’s democracy in trouble(Sachs and Warner, 2001&1997; Manzano and Rigobon, 2001; Auty, 2001; Ross, 2003).

Lastly, NNPC has the greatest blame to share in putting Nigeria’s economy into jeopardy (Table 5 (2021) of this investigation refers). The operations of NNPC must completely be overhauled with the right personnel employed for the right positions, to save the remaining part of the economy from complete collapse and revive the collapsed ones.

Conclusions

Going by the journey so far, it would seem irresponsible for NNPC to still indulge in the practice of petroleum products importing; this is short of the Nigerian dream. Nigeria has invested in the construction of four petroleum products refineries with numerous distributing deports and storage facilities scattered all over strategic locations of the nation. Despite this huge spending in tranches of several billions of dollars, the nation’s consumers continue to suffer shortages. Sadly, heavily subsidized importation of refined products has become a normal part of the distribution chain phenomenon (Siddig et al., 2014; Business day, 2013).

Nigeria’s consumers are tired and frustrated despite all these amounts spent every year to improve the living standard of the common man on the street. They still live in abject poverty. (Siddig et. al, 2014b, and Freedom, 2004). This calls for an urgent overhaul and turnaround of the operations of NNPC as caretaker of the oil industry in Nigeria and by extension Nigeria’s economy.

It is high time Nigerians need to know whether the endowment of oil to Nigeria is a “curse or blessing”. Nigeria has been into oil development, exploration, exploitation, refining, and marketing since 1956 when the first oil well was struck in commercial quantity but yet, the poverty index for the country vice-avis other oil economies of the world are disturbing. Solace may however be sort from the findings of some renowned mineral economy researchers as presented below:

Ross (2003) observes that – “the problems created by abundant mineral wealth are not unique to Nigeria”.

Auty (2001), equally responded thus, “countries that are over-dependent on the mineral economy are most vulnerable to so many economic and political vices such as sluggish economic development” his view was also corroborated by Sachs and Warner (2001&1997) &Manzano and Rigobon (2001).

That, “corruption rate is abnormally great” as observed by Gylfason (2001”; Sachs and Warner (1999); Leite and Weidermann (1999). That, “unusually slow process of democratic involvement reigns supreme” in the views of Ross (2001a); Lam and Wantchekon (1999); and above all “volatile condition of civil unrest becomes a common feature” attributed too, Fearon and Latin (2003); Collier and Hoefler (2001&1998).

However, as a peculiar syndrome to Nigeria, in the view of this author, Nigeria “suffers from both blessings and curses as she enjoys bumper harvest in crude oil export but the agony in domestically refined oil products marketing and distribution”.

Author: Bankole Aderemi Razaaq

Bibliography and Web Resources

Akpoghome O.S and Badejo D (2006) Petroleum product scarcity: reviewing the supply and distribution of petroleum products in Nigeria, OPEC review volume 30, issue1 pp.27 – 40, March 2006

Amponsah, R and Opei, F.K (2017) Ghana’s downstream petroleum sector: An assessment of key supply chain challenges and prospects for growth. International Scholars Journal of Management and Business Studies ISSN 2167-0439

Auty, Richard, and Mikesell, Raymond (1998), Sustainable Development in Mineral Economies, New York: Oxford University Press, pp.6-84.

Auty, Richard M (1993), Sustaining Development in Mineral Economies: The Resource Curse Thesis, London: Routledge.

Auty, Richard M (1994) ‘Industrial policy reform in six large newly industrialized Countries: The resource curse thesis’, in World Development, Vol. 22No.l p.11-26.

Auty, Richard M (2004), ‘Economic and Political Reform of Distorted Oil Exporting Economies’, a paper presented at the workshop on Escaping the Resource Curse: Managing Natural Resource Revenues in Low-Income Countries, Center on Globalization and Sustainable Development, The Earth Institute at Columbia University, New York.

Brandiq (2013) An in-depth survey of petroleum products marketing activities in Nigeria. [Online].Available-http://brandiqng.com/2013/12/petroleummarketing [Accessed 23 September 2014]

Christopher and Adepoju (2012); An assessment of the distribution of Petroleum products in Nigeria, Journal of Business Management and Economics Vol. 3(6). pp. 232-241, June 2012 Available online http://www.e3journals.org ISSN 2141-7482 © E3 Journals 2012

Collier, Paul (2007), The Bottom Billion: Why The Poorest are Failing and What Can be Done, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp.

Collier, Paul (2009), ‘The Political Economy of Natural Resources: Interdependence and its Implications’ A Paper presented at the 10th Anniversary Conference of the Global Development Network (GDN) Kuwait, February 3-6, pp. 1-18.

Businessday (2008), ‘JomoGbomo MEND spokesman in an email sent to the Press’ In Business Day newspaper Available And Can Seen and sited at https:llwww.businessdayonline.com/index.php?view=articles&catid

Ehinomen C. and Adeleke A. (2012) an essential of distribution of petroleum products in Nigeria. Journal of Business Management and Economics, Vol.3 (6) p232 -241

Freedom. O (2004),” Petroleum product supply and distribution. Report of the special committee”. NNPC public affairs, Nigeria. http://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/about-bp/what-we-do/finding-oil-and-gas.html

Idemudia, Uwafiokun&Uwen E. Item (2006), ‘Demystifying the Niger Delta Conflict: Toward an Integrated Explanation’, Review of African Political Economy, No 109:391-406

Ismail Soile, HezekiahTsaku, Bilikisu Musa-Yar’Adua (2014) The impact of gasoline subsidy removal on the transportation sector in Nigeria, American Journal of Energy

Gruenspecht H. (2011) International energy outlook. Retrieved fromU>S Energy Informational Administration.

Joshua OlaniyiAlabi (2012) The dynamics of oil and fiscal federalism: challenges to governance and development in Nigeria Ph.D. Thesis Submitted to the University of Leeds School of Politics and International Studies (POLIS)

Ross, Michael (1999), ‘The Political Economy of Resource Curse’ in World Politics. London No 51, Pp. 297-322.

Ross, Michael (2001), ‘Extractive Sectors and the Poor’, in Oxfam America Report. Washington DC: Oxfam America. P.7

Soyinka, W. (1998) “Re-designing a Nation” A lecture delivered at the Nigerian Law School October 16 Lagos

Soyinka, Wole (2008), ‘An interview with Ritz Khan on the Niger Delta Crisis’ on Al-Jazeera Television viewed live at 20:00 hrs on the 22/07/2008 SPDC (2006), Shell Nigeria Annual Report, Port Harcourt: Shell Petroleum Development Company Ltd. Pp. 6-9.

Spero, Joan, and Hart, Jeffrey (2003), The Politics 0/International Economic Relations, Belmont CA: Wadsworth 1Thomson pp.174-9, 229-300.

Stiglitz, Joseph (2005), ‘Making Natural Resources into a Blessing rather than a Curse’, in Tsalik, Svetlana and Schiffrin, Anya (Eds) Covering Oil: A Reporter’s Guide to Energy and Development. New York: Open Society Institute. Pp. 13-4, 25.

The Economist (2008), ‘Risky toughness’.In The Economist. London: The Economist Newspaper Ltd, September 18. p. 26

The Economist (2009) ‘Hints of new chapter’.In The Economist. London: The Economist Newspaper Ltd, November 12. p. 27

The Economist (2009), ‘Nigeria’s hopeful Amnesty’.In The Economist. London: The Economist Newspaper Ltd, October 22. p. 25 The Economist (2009), ‘What if the President goes’. In The Economist. London: The Economist Newspaper Ltd, April 8. p. 27