Post COVID19 era: Integrative Chinese Emergency Medicine under the Dominance of Western Medicine in Hong Kong

Author: WONG Margaret Wai Yan

Introduction

In 1894, the British colonial government of Hong Kong sanctioned Chinese Medicine (CM) as “incompetent” in managing epidemics (Griffiths, 2009). After the end of the British colonial governance of 150 years in Hong Kong in 1997, the British style of the medical system initiated a minimal change that the dominance of Western Medicine (WM) had its historical solid, deep-rooted foundation to marginalize Chinese Medicine, which was still in presence due to the vital reason of CM’s lack of scientific evidence-based supports.

The Chief Executive’s policy address of 1997 stated the development of Chinese and Western Medicine. Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) was brought into the local policy for the legislative formulation of the registration ordinance and the development of regulatory bodies. In 1999, the Chinese Medicine Ordinance (Cap. 549) and the Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong were passed and established. In 2001, the Hospital Authority, the statutory body, promulgated a series of clinical research guidelines on Chinese Medicine in conventional medicine settings to pave the road for integration.

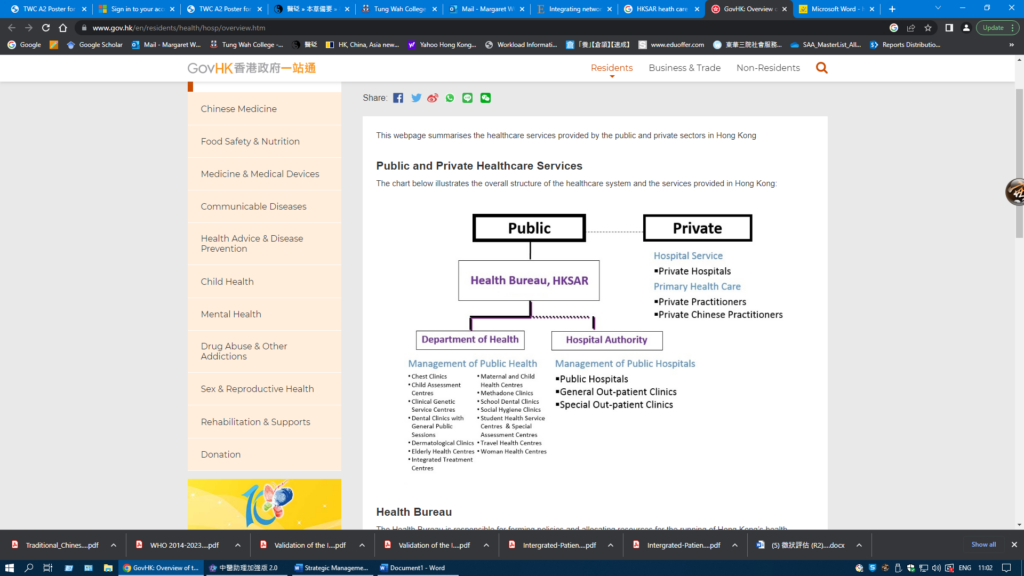

Since 1950, China has been one of the world’s healthcare systems, adopting a dual medicine system. China’s reunification of Hong Kong demonstrated the emergence of better Chinese Medicine development. The pre-dominance in the leading role of Western Medicine in the Hong Kong healthcare system ensured the role of Western Medicine as the “solo or major player” in the integrative public healthcare sector (Chung et al., 2009). Figure 1 is the overview of the position of Chinese Medicine and Practitioners in the Public Health Care System in Hong Kong.

Figure 1

The Overview of Chinese Medicine and the Practitioners in the Public Health Care System in Hong Kong.

Note: Most Chinese medicine practitioners in the private sector work solo to serve the community.

Source: Copied from “Overview of the Health Care System in Hong Kong (2023), https://www.gov.hk/en/residents/health/hosp/overview.htm”

Notably, TCM incorporation into the Western-dominated healthcare system could expand the array of choices for patients; however, the collaboration of Chinese Medicine with Western Medicine biomedical evidence-based medicine in the extent of implementation and practice of CM was a staunch challenge. This was ascribed to Western Medicine Doctors (WMDs) resistance to unconventional and non-evidence-based Chinese Medicine. (Ijaz 2019). Although the World Health Organization (WHO) Beijing Declaration (WHO, 2008) indicated the “communication between conventional and traditional medicine providers should be strengthened and appropriate training programs be established for health professionals, medical students, and relevant researchers” (WHO, 2013), the bio-scientific research studies for Chinese Medicine interventions and paradigms were criticized for low validity and low reliability (Ijaz 2019).

On the culprits of Chinese medicine’s lack of evidence-based support and regulations, the existing common disapproval from WM aroused unnecessary hostile attitudes towards Chinese medicine for the intervention of CM into the public healthcare system. Known to this for another country, the WHO had advocatedtraditional medicine strategy for 2014-2023 in response to the World Health Assembly resolution on traditional medicine (WHA62.13, WHO 2013). The updated plan for 2014-2023 put more emphasis on traditional and complementary medicine “product, practices, and practitioners.”

There was more room for Chinese Medicine to refine the evidence-based medicinal supports to align better with WM, and different integrative medical models produced by the multidisciplinary and inter-professional collaborative teams were structured. However, these newly invented models underpinned the contradictory power of relationship embedded with the inclusion of a Western medicinal form of literature and the exclusion of the historical age-old traditional Chinese Medicine concepts to improve the models biologically, chemically, and physically accepted.

China’s integrative medical system has adopted dual mainstream Chinese and Western medicine since 1950. In Hong Kong, the government strategically arranged Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) to be a “parallel profession” to Western Medicine (WM) (Hesketh & Zhu, 1997). Historically, Western medicine has predominantly monopolized medical pluralism in the public and healthcare sectors. The cross-hybrid principle of developing evidence-based medicine (EBM) for Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) was directed and limited to outpatient service. (Chinese Medicine Division, Hong Kong Hospital Authority 2008).

The advantages of adopting a pluralistic model in the public healthcare sector include providing alternative therapies for more patients’ choices and encouraging better communication, cooperation, coordination, unity, sharing, and respect among doctors and practitioners. However, this model did not render objective standards to compare the merits of WM and TCM (Kaptchuk, 2005). Accordingly, the EBM did not succeed with perfect integration. The formal institutional integration and development resulted in difficulties and slow progress. Despite the TCM services provided in the public healthcare sector in outpatient units, the structure for integration was not well established. For example, formal inter-professional referral networks have not been built up in public or private healthcare sectors. The Hong Kong TCM policy focused on regulating and professionalizing Chinese Medicine Practitioners (Chung et al., 2011, CMCHK, 2023).

Until now, the roles and responsibilities working on integrative medicine among the two CM and WM professionals were ambiguous, along with the integration of evidence-based and conditioned specific referral protocols in integrative services (Chung et al., 2021). Hong Kong’s TCM policy for structurally and functionally linking WM and TCM professionals has been minimal. This was revealed in March 2020, when the Hong Kong government expanded the CM services by subsidizing the daily operations of 18 public Chinese Medicine district clinics with annual provision for operation from HK$94.5 million in 2015-2016 to HK230 million in 2021-2011 (Research Office HK, 2022). Even if the sponsorship to CM service, the monopolized WM primary provider of secondary and tertiary care in the public healthcare system stated their consensus that WMDs did not accept any referrals from private CM practitioners (CMCHK, 2023). Although the HK Government vehement supports the “parallel fashion” of medical pluralism to “encourage cooperation, research, and open communication and respect between practitioners,” the honest disagreement among practitioners and doctors in the referral system could be seen for WMDs struggling to preserve the involved treatment system (Anderson et al., 2019).

One of the critical concerns regarding the difference in background training and culture between Chinese and Western medicine was that it produced misalignment and poor communication. The “low congruence in the validity of bio-scientific research methods about the Chinese medicine paradigm.” (Ijaz, 2019) facilitated the “professional monopolizers” of WM in integrative medicine as WMDs owned their “countervailing power of facilitating or rejecting the use of TCM services’ (Chung et al., 2011, CMCHK, 2023). The dual leading professionals were divisive until COVID-19 struck the world’s perception of the ‘new medicine’ of Chinese Emergency Medicine.

COVID-19 in Hong Kong

The COVID-19 pandemic was a threatening challenge to Hong Kong’s healthcare system. Primary Health Care services in Hong Kong experienced an unprecedented increasing burden of preventing, responding, and recovering from the pandemic emergencies. Before the fifth wave of the pandemic in December 2021, Chinese Medicine was assumed to be a primitive complementary and proactive disease prevention medicine. It promotes health and longevity. Its role was not deemed to be a gatekeeper. During the fifth wave and post-pandemic period, it was revealed that Chinese Medicine had a crucial role in that it could be demonstrated by working on holistic and preventive primary health care medicine and treating acute and chronic illnesses.

As no specific drug can be found to treat acute COVID-19 and long-term COVID symptoms, the depletion of over-the-counter pain relief and fever medicines with caseloads skyrocketing made Chinese Medicine the front-line medicine to work against COVID-19. Clinical experience showed that using Chinese Medicine effectively treated acute COVID-19 and long-term COVID-19 symptoms cases and reduced mortality rate. With the protracted imminent threats from the hauled pandemic and voluminous health complications after infecting COVID-19, the segmented primary, secondary, and tertiary health care did not provide instant urgent services of Chinese Emergency Medicine to the public.

With the structural and functional development of primary, secondary, and tertiary health care, emergency and severe cases management capacity was imminent for Western Medicine in that Chinese Medicine being commented notoriously for ‘unconventional,’ ‘unorthodox,’ and ‘unscientific’ practice claimed to be capable of managing urgent and severe cases was put in the sideline. The marginalization of CM to the outpatient sector was not a mutually beneficial way to provide effective and efficient treatments for patients who were infected with COVID-19 in urgent need of filling the effectiveness gap of treatment from Western Medicine. Whether the integration was proposed in horizontal or vertical manners, the “Health for All” underpinning the better and broader choice for patients can be in the link of all levels of the health care system.

Historically, Chinese medicine has practiced immediate palliative interventions in emergencies, which have been documented as effective and non-invasive. In Hong Kong, Primary Health Care services cover 90% of illnesses. Hong Kong experienced complex emergencies that were exacerbating COVID-19; primary health care bore double burdens during and after the post-pandemic period. The burdens are not only the unfinished agenda of chronic health problems but also the emerging challenges of communicable and non-communicable diseases, threats of pandemics, and the global climate changes eliciting diseases and their health consequences.

With the active participation of Chinese Emergency Medicine, primary health care has produced a new mode of medicine for preventive and emergency care during a pandemic. It is revitalized to play an essential role in fighting against COVID-19. The epidemiological exorbitance of its succession of virus or bacterial infection episodes will endlessly elicit the prevalence of chronic ailments. Chinese Medicine’s role of remaining a gatekeeper of primary health care and becoming a front-line sentinel in treating emergency and severe cases can have its capability to fill in the gap across different levels of care, including primary, secondary, tertiary, and even quaternary levels of cares to enhance coordinated and continued care under the dominance of Western Medicine in the present integrative system.

In Hong Kong, the regional strategy was initiated to develop Chinese Medicine by establishing the Government Chinese Medicine Testing Institute and the Chinese Medicine Regulatory Office. It has been collaborating with WHO Collaborating Centres for Traditional Medicine to boost further CM development and pave the way for Hong Kong to become a global hub. The hub should attain the aim of WHO “Health for all” in that ‘One World, One Medicine’ for world health.

2003 SARS and 2019 COVID-19

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) is a viral respiratory disease caused by the virus SARS-CoV-1. It was the first identified strain of the SARS-related coronavirus in the 2003 epidemic. The first known case was found in November 2002, and the syndrome could have caused the 2002–2004 SARS outbreaks (Leung, 2007) (He & Hou, 2013). During the SARS epidemic 2003, integrative medicine was adopted to apply Western and Chinese Emergency Medicine in treating SARS patients. The First Affiliated Hospital of TCM University in Guangzhou was attained as the leading institution in advocating the use of TCM in treating SARS. All seventy patients with SARS were treated in combination with bio-medicine at this hospital. The mortality rate in patients and the prevalence rate in medical staff were counted to be 0%, the overall mortality rate for patients was 9.6%, and the prevalence rate in medical staff was 22% worldwide. (He & Hou, 2013).

SARS spread via central airborne transmission, which caused worldwide alertness. This epidemic resulted in 744 deaths, with a 9.6% fatality rate. Western medicine employed routine symptomatic treatment. Chinese Medicine Practitioners played two roles in applying an adjuvant therapy in patients with SARS and achieved another role in preventing acute and critical diseases (He & Hou, 2013).

During SARS, the integrative interventions of WM and CM were endorsed and supported by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. From the literature review of Leung (2007), the results found that the combined treatment using Chinese Medicine and Western Medicine demonstrated positive efficacy, including “better control of fever, quicker clearance of chest infection, lesser consumption of steroids, and other symptoms relief in a few reports” (Leung, 2007)

A research study was conducted on a modified CM herbal formula for 3160 healthcare workers in a trial period of two weeks. These healthcare workers were assigned to be the high-risk group due to their susceptibility to getting SARS in the hospital. Results illustrated that “none of the consumers of the herbal formula contracted SARS infection, while there was 0.4% incidence among non-consumers. Adverse effects of this herbal formula were mild and infrequent. The consumers of the herbal formula hardly had any influenza-like symptoms, and their quality of life improved” (Luo et al., 2019). This study aimed to prove that Chinese medicine could prevent SARS infection.

Another research study also reported that Chinese Medicine applications in treating SARS were adjuvant therapy to the standard Western medicine therapy with a clinical trial on 50% of the infected patients in China. The result showed “positive though inconclusive indications regarding the efficacy of the combined treatments. Positive effects of using adjuvant herbal therapy included better control of fever, quicker clearance of chest infection, lesser consumption of steroids, and relief of other symptoms” (Luo et al., 2019). In 2019, another pandemic hit the world’s health: coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Chinese Emergency Medicine and Western Emergency Medicine were at an urgent time to orchestrate the combined efforts to fight against the more potent virus that threatened hundreds of millions of lives in the world.

On the rampant spreading of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID19) during mid-September 2020, more than 200 countries and territories hadreported 30 million confirmed cases of COVID-19 caused by SARS-CoV-2 including 950,000 deaths, supportive WM treatment was assumed to be the dominant therapy for COVID-19. (Varon 2020).The World Health Organization reported that four candidate drugs, including remdesivir, wereineffective or had little effect on COVID-19. In China, according to China News, 90 % of Chinese patients infected with COVID-19 adopted TCM, which reported an effectiveness rate of 80 % and no deterioration in patients’ condition for urgent case management. (An et al. 2021).

Interventional therapies using Traditional Chinese Medicine for treating COVID-19 have achieved significant clinical effects. Chinese Medicine (CM) has been employed to treat Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia in China. The meta-analysis evaluated CM’s clinical efficacy and safety in treating emergency COVID-19 pneumonia. Results illustrated that “7 valid studies involving 681 patients were included. The meta-analysis exhibited that compared to conventional treatment, CM combined with conventional treatment significantly improved clinical efficacy and significantly increased viral nucleic acid negative conversion rate. CM also prominently reduces pulmonary inflammation and improves host immune function.

Meanwhile, CM did not increase the incidence of adverse reactions” (Sun et al., 2020). Although Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) has been developed historically and used to treat acute and urgent illnesses for thousands of years, TCM had been widely perceived in WM societies that TCM might only be effective in managing chronic diseases. (He & Hou, 2013).

During the fifth wave of COVID-19 in April 2022 in Hong Kong, the hope spotlight shined upon the effectiveness of Chinese Medicine in treating COVID-19-infected people. The fast recovery gave a great shock to the WM. It extended great successes in the intensive care unit when the patients infected with COVID-19 had severe presentations at the emergency acute stage. This encouraging result impeded planning and developing Chinese Emergency Medicine (Cheung, SCMP 2022).

Managing emergency and severe cases inChinese Emergency Medicine was a great challenge. In January 2020, the World Health Organization announced that the COVID-19 novel virus was the world’s “public enemy No.1”. Although varieties of drugs, including antivirals, antibiotics, vitamins, and mechanically assisted ventilation, were put forward in front-line emergency management in an attempt to save patients’ lives, they were scientifically and clinically tested and failed to eradicate this severe illness. Patients who were assessed to be critically ill and required intubation with assisted mechanical ventilation were evaluated in their survival rate, reaching only below 20%. (Varon 2020).

From the remarkable difference from conventional orthodox medicine, Chinese Emergency Medicine could reach another level of medicinal potential by incorporating Western Emergency Medicine in a viable list of treatments. With the practitioners’ and doctors’ orchestrated efforts and the symptomatic herbal therapy in China, a first-cured patient was reported on 24 January 2020. By 27 January 2020, the Chinese government announced and released the herbal treatment program to prevent and treat the patients infected with COVID-19 (Varon 2020) and other adhered complications of COVID. According to China News, 90 % of Chinese patients infected with COVID-19 given TCM interventions had a reported effectiveness rate of survival of over 80 %, and no cases of deterioration were reported. (Xue et al. 2021). Western Emergency Medicine (WEM) had an interface with Chinese Medicine.

Application of Chinese Emergency Medicine in IM

The clinical practice of combining applications of TCM and scientifically advanced bio-medicine has generated a widespread medical practice, particularly in TCM hospitals in China; this dual application could provide a way to express the functions of Chinese Emergency Medicine was not only limited to the pandemic, it could be applied against a range of other acute and urgent illnesses such as epidemic hemorrhagic fever, dengue fever, viral meningoencephalitis, epidemic encephalitis B, viral myocarditis, epidemic cerebrospinal meningitis, pneumonia, acute cholecystitis, and acute pancreatitis (Peng et al. 2000), to name a few. In Hong Kong Western Medicine hospital, the management of the above-mentioned diseases are dominated solely by the WMDs, the role of TCM Practitioners (TCMPs) were often rejected in participation of active fighting against COVID19 and other emergency cases management.

Meta-analysis on Effectiveness of CM against COVID-19 on top of Western Medicine

In China, interventional therapies with Traditional Chinese Medicine for treating COVID-19 had achieved significant clinical effects,Chinese Medicine had been allowed to be used to treat Novel Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia. To reinforce efficacy and safety, a meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate CM’s clinical efficacy and safety in the treatment of emergency COVID-19 pneumonia. Results showed that “7 valid studies involving 681 patients were included. The meta-analysis exhibited that compared to conventional treatment, CM combined with conventional treatment significantly improved clinical efficacy and significantly increased viral nucleic acid negative conversion rate. CM also prominently reduced pulmonary inflammation and improved host immune function. Meanwhile, CM did not increase the incidence of adverse reactions” (Sun et al., 2020). With the immediate effect of controlling and treating diseases for further deterioration and complications incurred, Chinese Emergency Medicine should not overlook emergency and urgent illnesses.

Conclusion

It was a dynamic process and depended on the country’s policy of implementing dual medicine to initiate the management of acute and emergency cases. COVID-19 did exhibit the effectiveness gap of WM. The operational health care practice and changing fields incorporating an unfamiliar and doubtful medicine need more inter-professional collaboration and training to improve communication and overcome CM stereotypes of unsafe and inefficacy. The lack of modern scientific knowledge and evidence-based support of Chinese Medicine can be structured by innovative means to transform a thousand-year-old heritage medicine into a full-fledged research attainable medicine that can incorporate modern scientific bio-medicine. Orchestrated model formation would be a systematic force for positive impact on practitioners and doctors to put integrative theoretical models into practice to enhance the broader horizon to treat unprecedented diseases, contributing to world health and medical advancement.

Reference

An, X., Zhang, Y., Duan, L., Jin, D., Zhao, S., Zhou, R., … & Tong, X. (2021). The direct evidence and mechanism of traditional Chinese medicine treatment of COVID-19. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy, 137, 111267 and medicine, 1(2), 5-7.

Anderson, B. J., Jurawanichkul, S., Kligler, B. E., Marantz, P. R., & Evans, R. (2019). Interdisciplinary Relationship Models for Complementary and Integrative Health: Perspectives of Chinese Medicine Practitioners in the United States. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine (New York, N.Y.), 25(3), 288–295. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2018.0268

Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong, 2023https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/eng/#../../eng/main_index.htm

Chinese Medicine Division, Hong Kong Hospital Authority (2008) https://www.ha.org.hk/ho/corpcomm/Annual%20Plan/2008-09.pdf, https://www.cmro.gov.hk/html/eng/whats_new/COVID-19_anti-epidemic/chinese_medicine_services_under_the_hospital_authority.html

Cheung, Elizabeth (2022). South China Morning Post, https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/health-environment/article/3174411/coronavirus-can-hong-kong-become-hub-traditional

Chung, V. C. H., Ho, L. T. F., Leung, T. H., & Wong, C. H. L. (2021). Designing delivery models of traditional and complementary medicine services: a review of international experiences. British medical bulletin, 137(1), 70–81.https://doi.org/10.1093/bmb/ldaa046

Chung, V. C., Hillier, S., Lau, C. H., Wong, S. Y., Yeoh, E. K., & Griffiths, S. M. (2011). Referral to and attitude towards traditional Chinese medicine amongst western medical doctors in postcolonial Hong Kong. Social Science & Medicine, 72(2), 247-255.

Chung, V. C., Law, M. P., Wong, S., Mercer, S. W., & Griffiths, S. M. (2009). Postgraduate education for Chinese medicine practitioners: a Hong Kong perspective. BMC Medical Education, 9(1), 1-10.

Griffiths, S., (2009). Development and regulation of traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Hong Kong. Perspectives in Public Health, 129(2), 64-67.

He, J., & Hou, X. Y. (2013). The potential contributions of traditional Chinese medicine to emergency medicine. World journal of emergency medicine, 4(2), 92–97. https://doi.org/10.5847/wjem.j.issn.1920-8642.2013.02.002

Hesketh, T., & Zhu, W. X. (1997). Health in China: traditional Chinese medicine: one country, two systems. Bmj, 315(7100), 115-117.

Ijaz, N. (2019). Related attitudes among Chinese medicine students at a Canadian college: a mixed-methods study. Integrative Medicine Research, 8(4), 264-270.

Kaptchuk, T. J., & Miller, F. G. (2005). Viewpoint: what is the best and most ethical model for the relationship between mainstream and alternative medicine: opposition, integration, or pluralism? Academic medicine: journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 80(3), 286–290. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200503000-00015

Leung, P. C. (2007). The efficacy of Chinese medicine for SARS: a review of Chinese publications after the crisis. The American journal of Chinese medicine, 35(04), 575-581.

Luo, Y., Wang, C. Z., Hesse-Fong, J., Lin, J. G., & Yuan, C. S. (2019). Application of Chinese medicine in acute and critical medical conditions. The American journal of Chinese medicine, 47(06), 1223-1235.

Peng SQ, Zhang ZW, Yang J, Shen QF, Lin PZ(2000), Advanced Serial Books of Traditional Chinese Medicine: Study of Epidemic Febrile Disease. Peking: People’s Publisher of Health

Research Office (2022), Research and Information Division, Legislative Council Secretariat,17 August 2022.

Sun, C. Y., Sun, Y. L., & Li, X. M. (2020). The role of Chinese medicine in COVID-19 pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38(10), 2153-2159.

Varon, A., Varon, D. S., & Varon, J. (2020). Traditional Chinese medicine and COVID-19: should emergency practitioners use it?. The American journal of emergency medicine, 38(10), 2151–2152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajem.2020.06.076

Xu, J., & Xia, Z. (2019). Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM)–Does its contemporary business booming and globalization really reconfirm its medical efficacy & safety?. Medicine in Drug Discovery, 1, 100003.

World Health Organization (2008), Beijing Declaration, WHO congress on traditional medicine and the Beijing Declaration. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/74355

World Health Organization (2013) Traditional Medicine Strategy 2014–2023. http://www.who.int/medicines/publications/traditional/trm strategy14 23/en/