Risk Management Course

Companies worldwide, particularly in Africa south of the Sahara, are facing the globalization of the economy and the globalization of markets. To cope with these accelerated changes, companies have been forced to invest in innovation to improve their productivity and remain competitive to ensure their sustainability.

However, creations cannot be made without risks that hinder their development. Indeed, the economic environment has become very unstable and vulnerable to various fluctuations in the monetary sphere; faced with these multiple disturbances, credit institutions are increasingly threatened by various risks affecting their activity and their position in the financial market. In this perspective, our exploratory research problem aims to identify and measure the risk factors associated with business development, particularly economical and non-financial risks.

Credit risk is now considered the most critical risk faced by companies, banks, and financial institutions. However, in juxtaposition to this risk, banks are confronted with another category of risk long treated in a secondary way, namely non-financial risks. The trend today is to integrate these different risks for better performance of these institutions. We will first focus on the general approach to financial and non-financial risk. We will present the various financial and non-financial risks related to economic activity, and finally, we will discuss the measures and methods of measuring them.

To solve our problem, we proceeded in the theoretical part to review the literature on the company’s management in general and the direction of the particular risks.

Through this analysis, it will be highlighted:

- The characteristics of a successful business;

- changes in a business and risk – patterns of change in the industry, change in business strategy, change as a means of coping with risk;

- definition of risk, risk analysis;

- the risk management process;

- the risk assessment process;

- risk assessment mechanisms in SMEs.

1. Definitions

Risk can be defined as a possible danger that is more or less possible. According to NAULLEAU Gérard and ROUACH Michel (1990), risk designates “a commitment bearing uncertainty endowed with a probability of gain and harm, whether a degradation or a loss.” In this same vein, Hansson (2004) asserts that a risk is an undesirable event likely to occur. Therefore, through the analysis of Naulleau, Rouach, and Hansson, we can affirm that the specific characteristic of risk is the temporal uncertainty of an event having a certain probability of occurring and putting an institution, a company, or even a possibility.

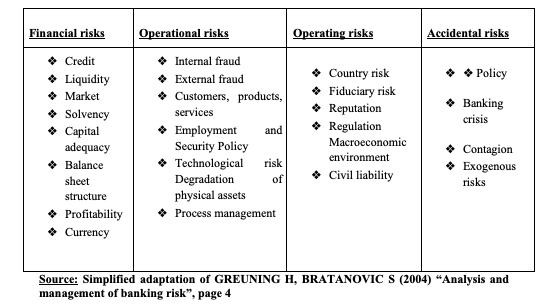

2. Typology of risks

2.1. Financial risks

In a broad sense, financial risks correspond to the risks inherent in banking and financial activities and can potentially concern all economic agents. Due to their essential banking and financial activities, banks and financial institutions are at the forefront of the players affected by these financial risks. Thus, they are subdivided into two (02) types of risks:

- Pure threats: (liquidity, credit, and insolvency risk) can cause losses for a bank when they are not well managed.

- Speculative bets: based on financial arbitrage, can generate a profit when the arbitrage is good or a loss when it is terrible. The main theoretical risk types are interest rate, currency, and market price (or position) risk.

2.1.1. Market risk

This is the risk of loss or devaluation on positions taken following price variations (prices, rates) on the market. This risk applies to the following instruments: shares, foreign exchange, commodities, etc.

2.1.2. Liquidity risk

The liquidity risk of a company is materialized by an inability to honor its short-term payments (reimbursement of bank debt, supplier payments, salaries, tax debts, etc.); in other words, the liquidity risk is the risk of cash shortage, i.e., the inability of a company to meet its commitments in the short term (over less than one year). Such liquidity problems can then lead the company to a situation of insolvency or even bankruptcy.

2.1.1. Credit risk

Credit risk is the risk that the debtor does not meet his initial obligation to repay a loan. As soon as the customer returns his debtor account, the bank is called upon to bear credit risk.

2.1.2. The risk of insolvency

The risk of insolvency is that a debtor customer of an invoice will become unable to make the payment voluntarily by dragging out the price or involuntarily if it is placed under the collective procedure.

2.1.3. Interest rate risk

Interest rate risk corresponds to the possibility of a company, or an investor, being negatively impacted by a change in interest rates. It corresponds to the possibility that a fall in interest rates penalizes the return on its investments or increases the interest expense of its sources of financing.

2.2. Non-financial risks

Non-financial risks cover risks that financial institutions do not voluntarily take in the exercise of their activities (unlike, for example, credit and market risks). Still, they are incurred once the transactions have been carried out due to external constraints of a legal or regulatory nature or internal to the organization (processes, information systems, human resources, etc.).

2.2.1. Operational risk

This is the “risk of direct or indirect loss from an inadequacy or failure attributable to procedures, personnel, internal systems or external events.” This risk includes:

- internal fraud (theft, etc.);

- external fraud (forgery, damage due to computer hacking, etc.);

- complaints of discrimination and civil liability in general.

- customer practices.

- products and commercial activity.

- money laundering and sale of unauthorized products.

- damage to physical property (acts of terrorism, vandalism, earthquakes, floods, and fires);

- Business interruption and system failures (computer hardware and software failures, telecommunications problems, and power outages).

2.2.2. Operating risks

Operational risks relate to the bank’s business environment, including macroeconomic issues, legal and regulatory factors, and the financial sector infrastructure and payments system.

2.2.3. Accidental risks

Accidental risks include all kinds of exogenous risks which, when they materialize, can compromise the bank’s activity or financial situation as well as the adequacy of its capital.

3. Financial risk control measures

All financial institutions must implement sound procedures to identify, measure, monitor, and control risk. As CONSO P (2001) says, “Risk is omnipresent, multifaceted, it concerns all the employees of the company and course the general management, but also the shareholders at the level of the overall Risk of the company. The fight, therefore, concerns all the actors”.

3.1 Credit risk

Rouach and Naulleau (1998) define credit risk as “a commitment bearing uncertainty endowed with a probability of gain and harm, whether this is a deterioration or a loss”; Sampson (1982) considers that “the tension that lives in bankers is inseparable from their job, they watch over the savings of others, and therefore they make them benefit by lending them to others which inevitably entails risks.” In general, it is; therefore, the expected loss on credit is a random variable that, associated with the uncertainty on the default horizon, constitutes the credit risk.

As part of their exercises, credit institutions must consider many threats that affect credit risk.

The table below summarizes the credit risk threats:

Table 1 : Representation of credit risk threats

3.1.1 Financial analysis

Financial. This is probably the method that is both the oldest and the most used in risk analysis, which will thus make it possible to establish different ratios and calculations to verify the company’s performance through its income statement and balance sheet. For Alain MARION (2015), it can be defined as a method of understanding the company through its accounting statements. This method aims to make an overall judgment on the company’s performance level and its situation. And finally, (Ndaynou, 2001), the purpose of economic analysis is to establish a diagnosis of the company’s financial4 condition and to pass judgment on its economic equilibrium, i.e., its solvency, profitability, and autonomy. To do this, Ndaynou (2001) translates his analysis into two elements:

The future cash flow: is calculated by the difference between the inflows and the outflows of the flows made by the company’s activity. It shows the ability of the debtor to repay his commitments without jeopardizing his activity during a loan. The future cash flow makes it possible to monitor the evolution of profits and ensure they are sufficient for the working capital requirement.

Working capital allows one to appreciate the organization’s financial balance.

It indicates whether the company is sustainable and can meet its commitments. For the calculation, there are two methods: Either from the top of the balance sheet with the difference between stable resources (equity and long-term debt) and less stable uses (net fixed assets), or the bottom of the balance sheet with the difference between current operating assets and short-term debts. This method does not provide perfect information about the causes of borrower default. Its perception through indicators provided by the company remains insufficient for decision-making because it is based on past accounting statements. Banks can use other methods to complete this analysis, namely qualitative methods that must consider the environment and competition in the markets in which it operates to assess the context in which the company lives. The strategy must be detailed, both from the perspective of the strategic diagnosis (position of the company at the time of the diagnosis) and in terms of the choice of a development strategy (political and tactical).

3.1.2 Le scoring

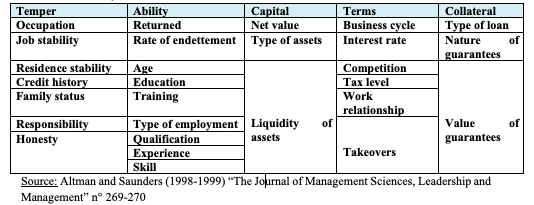

One of the most popular methods in credit risk assessment is credit scoring. It relies on the information of the five “Cs” (Character, Capacity, Capital, Collateral, Conditions) to examine loans.

Scoring, also called credit scoring, is a method widely used by banks as a decision-making tool. This technique, according to MESTER L.J (1997), is defined as “a statistical method to predict the probability that a loan applicant (the debtor) will default. It is a simple expert system, often used in the environment of medium-sized companies (ETI) and small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). This analysis is not conducted by the companies themselves but by institutions outside these organizations. We can mention the French insurance company for foreign trade (COFACE), a significant player in this sector, to help these companies. The financial institutions that grant credit use this method internally, thanks to their statistical databases.

According to VAN PRAAG N (1995), the objective is “to determine a score, that is to say, a level supposed to represent a particular risk for the lender. This score is obtained by taking into account various parameters, the choice of which is essential in terms of the predictive capacity of the system. After carrying out this numerical evaluation, you must integrate the score obtained into a previously calibrated assessment grid. However, reading a score presupposes the determination of a risk grid, which will allow the interpretation of the figure obtained and help the lender make the final decision.

Van Praag (1995) explains, “Scoring is like a decision support tool but should not be a discriminating criterion for decision making.” The design of a Scoring model, therefore, follows a relatively standard procedure which is:

- Step 1, define the event to detect.

- Step 2. Build the sample: Two sub-samples are needed: one made up of companies that have experienced the event to be detected (default, bankruptcy), the other of companies that have not experienced it, deemed healthy.

- Step 3. Define the horizon of the measurement: According to this horizon, the data processed will go back to a historical period before the bankruptcy, more or less long

- Step 4. Choose the explanatory variables of the event: The selection of variables is delicate; it depends, first, on the data that the model will be able to process (quantitative and qualitative)

- Step 5. Choice of the statistical method: to seek the best performance

- Step 6. Modeling and testing

- Step 7. Passing from the scores to the probabilities of occurrence: if the model does not directly provide the likelihood of failure.

- Step 8. Control and maintain the model: Any Scoring model is sensitive to changes in general economic conditions and the situation of companies.

But the first credit-scoring models were developed by BEAVER W.H (1966) with the basis of scoring research; It is with ALTMAN E. I (1998) and SAUNDERS A. (1999) that the models were perfected over time to lead to a discriminant analysis called the Z function. This will become the ZETA function and allow a complete discriminant analysis thanks to the improvements of ALTMAN, NARAYANAN, and HALDEMAN.

The “5 Cs” method

This method invites the Credit analyst to conduct investigations to have an opinion relating to 5 major components, making it possible to assess the risk. In other words, the assessment of credit risk passes first and foremost through a good mastery of all the dimensions designated under the 5Cs associated with the criteria which underlie not only the quantitative aspects (commercial risk, financial risk) but also the qualitative aspects (managerial risk, business risk) of risk – credit considered among the oldest decision-making models in terms of credit (Altman and Saunders, 1998; Saunders, 1999).

- Capacity: It is the study of the capacity to respect the credit committee of the borrower’s financial situation. Debts (and their expected service) are compared to the company’s results, and the borrower’s ability to service the debt with future cash flows is examined. For capacity, purely financial criteria are distinguished (monthly income and expenses).

- Character: This is the company’s reputation, both in the market and with its creditors, able to interpret the payment history (track record). It is based on the borrower’s reliability, honesty, and good faith. We refer to the borrower’s integrity and intention to repay or not and to make any efforts in the event of difficulty.

- Capital: We examine both the financial structure of the company and the importance of the funds provided by the shareholders (Equity), but also the possible capacity of the latter to make an additional contribution to finance the project at the origin seeking financing or in the event of a financial crisis. In European logic, we measure the working capital.

- Collateral: This is the study of the underlying assets that can potentially secure the credit. This dimension allows us to determine the nature and value of the guarantees available to the client.

- Conditions: We consider the conditions (market and commercial) applicable to this borrower. In other words, it is a question of assessing whether the states (rate, maturity, method of repayment) applicable or envisaged do not generate too high a risk and whether they are such as to allow the creditor to develop a fair remuneration for the risk of supported credit. The 5 Cs method can be summarized as follows:

Table 2: Summary of the five Cs of credit

3.1.3 The rating

The rating or creditworthiness reflects the credit quality of an issuer. External financial specialists carry it out. This technique is used by rating agencies, credit insurance companies, or the Banque de France with the FIBEN file (corporate bank file). These institutions use both qualitative and quantitative data to conduct their analyses. However, qualitative criteria are still preferred for analyzing and judging the quality of the issuer.

To carry out this rating, the main elements retained are:

- Company activity

- The positioning of the organization on the market

- In the balance sheet, both short-term and long-term liabilities

- The composition of the capital

- Cash flow and future income

- The situation of the company

The rating is an exciting tool that gives an overall view of an organization or product situation at a specific time. It should be remembered, however, that this analysis is not perfect. To make a viable decision, it is necessary to cross other information. Indeed, during the subprime crisis, some rating agencies gave very high ratings to financial products or companies that were not recommended on the credit market. This proves that the rating should be used cautiously to be genuinely effective depending on the economic situation.

3.1.4 VAR (Value at Risk)

VAR is a simple tool that makes it easy to interpret a level of risk. To measure the proportion of threats, it is necessary to have a certain level of probability based on statistics, which does not constantly reassure investors. VAR is a technique that determines a maximum potential loss based on duration and degree of confidence. JP Morgan has democratized the VAR model, a common practice in financial risk assessment. For SAUNDERS A, and ALLEN L (2002), the objective is to measure the variation in the future value of a portfolio about the change in credit quality. To estimate the VAR, there are three statistical methods:

- historical VAR;

- Parametric VAR;

- Monte Carlo VAR.

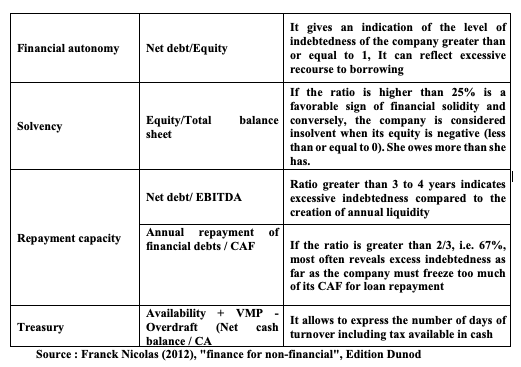

3.2 Ratio methods

Table 3 : Financial structure analysis table

There is also:

- The risk coverage ratio obliges credit institutions to demonstrate that their net equity covers at least 8% of all their loans.

- The risk division ratio prohibits credit institutions from making commitments in favor of a single customer for an amount exceeding 75% of their net equity and, in turn of their large customers or significant risks (commitments greater than 15 % of net equity) for several loans greater than eight times their net equity. The 75% limit will later be reduced to 45% of the bank’s adequate funds.

3.2.1 Liquidity risk

The concept of liquidity translates in terms of cash, the requirement of solvency: the ability of the company to meet its commitments in the event of liquidation Thomassin and Gagnon (2000) Marion (2001). We think on a short-term horizon.

For Marion (2001), Adelman (2001), and Mark (2001), the analysis of liquidity must be extended and take into account all of the liabilities to be able to ensure that the maneuver undertaken by the company to maintain its financial sustainability is not akin to a simple headlong rush allowing you to postpone your inability to meet your deadlines until later. From a liquidity perspective, two keywords emerge from credit risk assessment models: cash flow and working capital.

Self-financing capacity is a concept of overall operating liquidity, according to Teulié and Topsacalian (2000). While Marion Adelman and Mark (2001) define it as an indicator of a potential monetary surplus as far as it is calculated from the turnover achieved, part of which the outstanding customer has not yet been cashed.

Rolling. Working capital, on the other hand, according to Marion (2001), provides the company with operating security, especially when the operating cycle is likely to experience sudden jolts, resulting in a temporary increase in fund requirements. In this situation, and especially if the company is over-indebted, there is an obvious risk of non-renewal of short-term bank loans. Marion (2001) maintains that the amount of working capital does not constitute sufficient information if one does not take into account, at the same time, its mode of financing, i.e., the distribution of resources between shareholders’ equity and financial debt.

Moreover, for Altman (1968), Zopounidis (1987), and Twarabimenye and Doferèta (1995), there are two classic measures of working capital in credit risk assessment models):

- the general liquidity ratio or operating capital ratio (current assets/current liabilities), the liquidity index,

- Immediate liquidity or cash ratio (existing assets – inventory – prepaid expenses) / (current liabilities).

Early warning signals about the liquidity problem are:

- Excessive reliance on inter-financial institution market funding and through brokers

- A sharp increase in the cost of financing (Cost of funds)

- A rapid fall in profits

- A decrease in equity

- Managements issus

- Unfavorable publicity

The list remains exhaustive.

3.2.2 Le ratio de liquidité

Le ratio de liquidité permet d’évaluer si l’entreprise est solvable à court terme.

Il existe deux méthodes de calcul :

- (Actifs circulants – stocks / dettes à court terme de moins de 1 an) x 100;

- (Créances clients + disponibilités / dettes à court terme de moins de 1 an) x 100.

Le résultat de ce rapport doit être supérieur à 1 pour que l’entreprise soit solvable à court terme. En effet, un ratio inférieur à 1 indique que votre entreprise ne pourrait pas faire face à une demande simultanée de remboursement de la part de tous ses créanciers. A l’inverse, un ratio trop important peut être le signe d’une gestion trop prudente de vos actifs.

Ce ratio peut être également attendu comme étant plus largement supérieur selon le secteur d’activité dans lequel vous exercez.

Pour une couverture de risque de défaut de liquidité, il existe le ratio de liquidité qui oblige les établissements de crédit à justifier en permanence des ressources immédiatement disponibles et susceptibles de couvrir au minimum l’intégralité de leurs dettes à échoir dans un mois au plus ; et le ratio de transformation à long terme dont le seuil minimum est 50 % entre les emplois et les engagements à plus de 5 ans d’échéance d’un établissement de crédit et ses ressources de même terme.

3.2.3 Le risque de taux d’intérêt

Pour Calvet H (1997) ce type de risque a pour origine l’activité même de l’institution financière qui consiste à réaliser des prêts à un taux inférieur au coût de sa collecte. Le risque de taux ne peut donc apparaître que si le coût des ressources devient supérieur aux produits perçus sur les emplois. Le risque de taux est de voir la rentabilité de l’établissement de crédit se dégrader par évolution défavorable des taux d’intérêt. Ce risque ne se matérialise jamais lors de la réalisation du crédit car, à un instant donné, il serait absurde qu’un établissement de crédit prête à un taux inférieur au coût de sa collecte. Le risque de taux ne peut donc apparaître que dans le temps et uniquement si des durées des emplois et des ressources ne sont pas parfaitement adossées (il y a adossement parfait lorsque les emplois et les ressources sont sur une même durée, préservant dans le temps la marge de la banque).

Le risque de taux d’intérêt est défini comme celui qui, sous l’effet d’une variation adverse des taux d’intérêt, détériore la situation patrimoniale de l’institution de crédit et pèse sur son équilibre d’exploitation. Toutes les institutions financières font face à un risque de taux d’intérêt.

3.2.4 Le ratio de couverture des intérêts

Le ratio de couverture des intérêts est un ratio d’endettement et de rentabilité utilisé pour déterminer la facilité avec laquelle une entreprise peut payer des intérêts sur sa dette en cours. Le ratio de couverture des intérêts est calculé en divisant le bénéfice avant intérêts et impôts (EBIT) d’une entreprise par ses charges d’intérêts au cours d’une période donnée.

Le ratio de couverture des intérêts est parfois appelé ratio de fois les intérêts gagnés (TIE). Les prêteurs, les investisseurs et les créanciers utilisent souvent cette formule pour déterminer le niveau de risque d’une entreprise par rapport à sa dette actuelle ou à des emprunts futurs.

4. Operational risk analysis

Wharton (2002) defines operational risk as a non-financial risk having three sources: internal risk (e.g., “rogue trader”), external risk, i.e., any uncontrollable external event (e.g., a terrorist attack), and strategic risk (e.g., a confrontation in a price war). For Kuritzkes and Wharton (2002), strategic risk is the most important. However, it is ignored by the Basel agreement.

4.1 Risks inherent in people and relationships between people

They relate to losses caused by employees, intentionally or not, or the relationships an institution has with its customers, shareholders, regulators, or third parties. They relate to losses caused by employees, intentionally or not, or the relationships an institution has with its customers, shareholders, regulators, or third parties. Political risks linked to the instability of a country or a geographical area may also be included at this level, which leads to avoiding excessive and long-term commitments. Finally, fraud and theft are not risks to be underestimated due to the manipulation of large sums.

4.2 Risks inherent in the procedures

They relate to losses resulting from the failure of transactions on customer accounts, settlements, or any other process of current activity. We sometimes talk about the processing of files and operations. These risks are linked to those of IT tools which, if they are unusable, can lead to total paralysis.

4.3 System Risks

Here we find the risks of the system relating to the storage of information in databases. These must remain permanently usable, particularly by customer advisers, forced to rely on this data to formulate an offer. They recover losses from business interruption or system unavailability due to an infrastructure or technical problem.

4.4 Risks inherent to third parties

They correspond to losses due to the actions of external elements, in particular external fraud, causing damage to movable and immovable assets. Regulatory changes that negatively affect business activity also fall into this category. Here we find the environmental risks that can cause the work tool to stop or even disappear: storms, floods, fire, etc.

5. Operational risk assessment and measurement methods

Instead, risk assessment is a qualitative approach in which internal loss data plays a less critical role since it reflects past trends and not present or future operational risks.

Risk measurement methodologies emphasize the importance of internal loss data. Quantification and measurement are only possible if we attach loss estimates to particular risk events and the likelihood of such an event occurring.

The Basel II framework provides for three (3) methods for calculating capital requirements for operational risk, in increasing order of complexity and risk sensitivity:

5.1 Basic indicator approach

For Hiwatashi (2002), in the indicator approach, variables such as “Gross Income or cost” are approximations for performance, and a certain percentage represents the bank’s operational risk exposure.

For Culp (2001), the “basic indicator” method is based on a few rigorously defined risk indicators. This method (Basic Indicator Approach or BIA), therefore, consists of a fixed calculation of the requirements (KL) based on the average net banking income of the bank’s last three financial years multiplied by a factor ∝ (15%): KL= 15% NBI.

5.2 Standard approach

Risk management is measured at the work unit level using a data review. The “internal ratios” are treated subjectively with quantitative ratios, specifically well-determined for the operational risk factors and each work unit. For Culp (2001), this approach considers “the lines of standard work.” the standard method (The standardized Approach or TSA), therefore, consists, for each line of the bank’s business, of a fixed calculation (beta= 12% to 18% according to the eight lines defined) of the requirements (KL) based on the net income average banking recorded on each line over the last three years.

5.3 Advanced Measurement Approach (AMA)

For Culp (2001), the AMA approach represents the method of internal ratios. This method of advanced measurement (Advanced Measurement Approach or AMA) consists of calculating the requirements (KL) by the internal measurement model developed by the bank and validated by the supervisory authority. Operational risk management achieves its maximum effectiveness when the culture of the bank emphasizes high standards of ethical behavior at all levels of the establishment because it is essentially a question of due diligence to be carried out, which is:

- a reliable and well-configured operating system

- effective procedures controlled by those concerned

- employees trained before assignment to the position, which implies knowing the skills required / position

- a priori self-control, effectively exercised by the line manager on each validation

- statistics of errors and incidents regularly kept and taken into account in the rating of agents

- the effective sanction of breaches

- effective and rigorous ex-post control in everyday situations as well as in crises

- recommendations effectively implemented.

In short, many operational risks are difficult to measure, and some cannot be estimated. Flat-rate methods are less complicated and less costly to set up, but they are not precise and do not give an accurate picture of the risk. Risk managers have realized that reflection on measurement methods is not enough to predict future events and that these results should be obtained by internal information (audit results, information sought by experts or Top Management); The evaluation should complement the measurement and quantification procedure.

The proposed methods (models) often have limits of complexity and uncertainties of incomparable results following the various definitions of operational risk adopted. Following these technical application problems and the disagreement with a single calculation method, the Basel Committee, in its last publication (June 2004), rejected the calculation method proposals (AMA, LDA, and Scenario analysis) and has given banks the freedom to apply their internal methods on two conditions, which are to prove the effectiveness of this method to the supervisory authority and to gradually evolve their flat-rate approaches towards more advanced and more complicated systems, which They cost more but are finer.

Conclusion

The purpose of determining, classifying, analyzing, and evaluating risks is, therefore, to limit the risks incurred by credit institutions as much as possible, thanks to the appropriate means that we have had to develop in our work.

The very nature of credit activity exposes financial creditors to risk; in other words, it is like credit institutions taking risks. Credit institutions are obliged to be prudent. This is why their activities are increasingly supervised, hence the multiples in danger and risk management. However, the latter must remain acceptable as far as the depositors and others provide a majority of the resources by the donors, who will have to be reimbursed at one time or another.

Credit risk is at the heart of financial concerns today. For this, the decision to grant credit has changed a lot in its methods of determination; giving credit is, therefore, a complex act because the institution will have to analyze the nature of the risks it incurs, estimate their probability of occurrence, and endeavor to anticipate the event of difficulties to counter or transfer them to determine risk coverage finally.

Bibliography:

Michel Rouach and Gérard Naulleau (1990), Banking and Financial Management Control: Key to Competitiveness, La Revue Banque

VAN PRAAG N, (1995), Credit management and credit scoring, Paris, Economica (Pocket management collection), p 112

SAMPSON A, Banks in a dangerous world, R.Laffont, 1982, p.38

MICHEL R and GÉRARD N (1998), Banking and financial management control, Revue banque

CONSO P, the company in 24 lessons, Dunod, Paris, 2001, page 260

MESTER L.J (1997), What’s the point of credit scoring, business review, Federal reserve bank of Philadelphia, p3-16

ROSENBERG E, GLEIT A (1994) “Quantitative methods in credit management: a survey”, operations research, vol 42, n°4, 1994, p 589-613

ALTMAN E.I, NARAYANAN P, HALDEMAN R.G (1977) “ZETA analysis: a new model to identify bankruptcy risk of corporation”, Journal of banking and finance, vol 1, n°1, p29-51

Hennie Van Greuning, S.B. Bratanovic (2004). Analysis and management of banking risk.

Jean-Philippe Svoronos (2010). BCEAO seminar on banking risks and Basel III reform.

Jezabel COUPPEY-SOUBEYRAN (2010). Money, banks, finance.

GREUNING H, BRATANOVIC S (2004) “Analysis and management of banking risk”, page 4

SAUNDERS A, ALLEN L (2002), “Credit ratings and the BIS capital adequacy reform agenda” Journal of banking and finance n°26, p 909-921

Culp, C., 2001. The Risk Management Process: Business Strategy and Tactics. New York: John Wiley & Sons

Calvet H. (1997) “Credit institution: Assessment, evaluation and methodology of financial analysis”, Economic Edition; Paris; p.78.

Hiwatashi, J., 2002. Solutions on measuring operational risk. Capital Markets News, the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, (September), 1-4.

NDJANYOU L (2001), risks, uncertainties and bank financing of Cameroonian SMEs, Center for Economic research on Africa, page 1-27

Michel Dietsch, J. Petey (2008). Measurement and management of credit risk in institutions.

Alain MARION (2001) “Financial analysis, concept and methods” DUNOD editions, Paris, p10

Teulié J. and Topsacalian P. (2000), Finance, Vuibert, 3rd Edition

HULL J. (2007), “Risk management and financial institutions”, Editions PEARSON, P. 441.

Michel Dietsch & Joël Petey (2003), “Measurement and management of credit risk in financial institutions”, Editions DUNOD, Paris.

Amelia GREENBERG (SPTF) and Justin Jules KOUTETE (UCEC-MK) (2020), “Liquidity Risk Management at the Level of Financial Institutions”.

Dietsch M., Petey J. (2003), “Measurement and management of credit risk in financial institutions”, Revue Banque Edition.

Cécile Kharoubi, Philippe Thomas: “Credit risk management: Bank & market”, Edition 2016.

Simplified adaptation of GREUNING H, BRATANOVIC S, “Analysis and management of banking risk”, 2004, page 4.

El KHOURY Badreddine and GUINDO Abdoulaye (2010), “Credit risk and non-financial risks”

GREUNING H, BRATANOVIC S (2004) “Analysis and management of banking risk”, page 4

Twarabimenye (1995). Business Loan Risk Assessment Model, 183 p.

DOFERETA y. (1997). “Assessment of credit risk in the context of the granting of credit to self-employed workers by a financial institution”

BEAVER W.H (1966), “Financial ratios as predictors of failure” Empirical research in accounting vol 4, p.71-111

Wharton (2002), “liquidity, asset prices and systemic risk”, in Risk measurement and systemic risk.

HEEM G. (2000), Internal control of bank credit risk, doctoral thesis, University of Nice – Sophia Antipolis

Author: THIOMBIANO Boubakar, student LIGS University

Approved by: Babandi Ibrahim Gumel, lecturer LIGS University