The Influence of rebranding on brand equity of 9mobile.

9mobile was rebranded in 2017 after one of its biggest shareholders pulled out and the telecommunication brand was rebranded, leading to an overhaul of its brand elements. The aim of this study was to investigate if the rebranding process has any influence on the brand equity, using the consumer-based brand equity (CBBE) dimensions of Aaker as guide. The commitment-trust theory was used to underpin this study and survey research design was adopted. The study selected 440 subscribers of 9mobile at the Federal Capital Territory of Nigeria, Abuja as participants. Analysis was done using both descriptive and inferential statistical tools. The results revealed that the subscribers had very strong awareness and association with the brand but perceived quality and brand loyalty were average. Further analysis revealed that awareness of the rebranding process had significant relationship with association but not with perceived quality and brand loyalty. This study thus concluded that 9mobile rebranding had no significant relationship with its equity. The current GSM subscriber statistics in the country lends credence to our findings.

All marketing activities are undertaken with the goal of changing or reinforcing the consumer’s mind-set in some way. This includes thoughts, feelings, experiences, images, perceptions, beliefs and attitudes the consumers have towards a brand or product. It is essential to know who the consumers are, which group they belong to or what they are buying, when, why, where, how and who is involved in the buying process. This is for no reason but because brand equity ultimately resides in the mind of the consumers (Pullig, 2008).

Muzellec and Lambkin (2005:805) describes rebranding as “the creation of a new name, term, symbol, design or a combination of them for an established brand with the intention of developing a differentiated (new) position in the mind of stakeholders and competitors.” This implies that rebranding involves the alteration of some or the entire brand elements in order to generate new look and consequently consumer perception about the product.

The motive to rebrand a product or an organisation vary from organisation to organisation, it depends on what the organisation wants to achieve, which can be to give it a new image, to reposition it among competitors, to increase market sales, to change consumers’ perception among others. Nevertheless, Daly & Moloney (2004), Stuart and Muzellec (2004) and other scholars see rebranding as a continuum that cannot end. They further posit that a brand will continue to undergo rebranding over time. This may be as a result of change of ownership, corporate strategy, competitive position and external environment as identified by Muzellec et al. (2003:33).

In marketing, the perception of the consumers about a brand matters a lot in business because the consumer’s perception about a brand determines the equity of such brand (Lin, 2015). Romaniuk and Nicholls (2005) note that the effectiveness of an organisation’s marketing efforts and the value of a product influence consumer’s perception of a brand and consequently determine the level of equity of such brand.

Previous studies have reported contradictory results regarding the link between rebranding and brand equity (or its dimensions). While some scholars found that rebranding have a positive significant effect on the quality of products (Saleh, 2016), influenced customers’ satisfaction (Mwangi, 2013), influenced profits and brand perception (Gikonyo, 2016), others reported that it had no moderating effect between service quality and brand loyalty (Bamfo, et al, 2018), no effect on brand equity (M’Sallem et al., 2009), no impact on perceived quality and customer satisfaction (Osei-Wusu, 2016).

It has been over three years that the rebranding process of Etisalat Nigeria was completed and the brand was rebranded to now 9mobile. The telecommunication brand began operation in Nigeria in 2008 with Emerging Markets Telecommunications Service Ltd and Etisalat International of the United Arab Emirates coming into partnership (Vanguard, 2017). In July 2017, Etisalat International pulled out of the partnership deal due to the problems Etisalat Nigeria ran into over a seven-year loan facility of $1.2billion from 13 local banks and their foreign counterparts to refinance a $650million loan as well as the expansion of its network which the brand could not redeem due to a dollar shortfall in Nigeria’s financial system (The Nation, 2017).

Furthermore, the United Emirate based organisation also ordered the Nigeria brand to change its brand name, logo, domain website and every other aspects of it that was related to Etisalat International. Sequel to this, on Thursday, July 13 2017, the rebranding process of the telecommunication service provider was completed and it became 9mobile, with logo, tagline – here for you, here for 9ja and website domain – 9mobile.com.ng.

As at the time of rebranding, the telecoms firm had the least number of subscribers in Nigeria, having 11.72% of the total GSM subscribers in the country with MTN Nigeria topping the log, followed by Glo and Airtel (National Bureau of Statistics, NBS, 2018). The main objective of this study is to investigate evaluate the implication of rebranding on its 9mobile equity, using the Consumer Based Brand Equity (CBBE) as guide. This study will examine the awareness, image/association, perceived quality and brand loyalty of 9mobile after the rebranding process. The specific objectives of the study are to:

- Examine the brand awareness of 9mbile after rebranding.

- Examine influence of rebranding on 9mobile association.

- Examine influence of rebranding on 9mobile perceived service quality.

- Examine influence of rebranding on 9mobile brand loyalty.

Literature Review

Commitment-Trust theory

The commitment-trust theory was developed by Morgan and Hunt (1994). The theory holds that trust and relationship commitment play key mediating roles in order to establish, develop and sustain successful relationships between different parties. According to the duo, commitment and trust are key factors in relationship marketing for many reasons. First, the two factors encourage marketers to preserve relationship investments together with their exchange partners. Second, they help marketers maintain relationships with existing partners for expected long-term benefits rather than being attracted by short-term ones. Finally, they enable marketers to believe that their partners may not take opportunistic actions, implying fewer potentially high risk actions (Morgan & Hunt, 1994). In short, the two factors play important roles in developing successful relationships between brand owners and the consumers.

As put forward by Mack (2014), rather than chasing short-term profits, businesses should follow the principles of relationship marketing in order to forge long-lasting bonds with their customers. For mutual understanding and benefits to exist between business owners and customers, business owners must build trust in the customers and be committed to their needs. This way, the needs of both customers and the business owner will be fulfilled.

This theory is relevant in brand marketing because, first, the customers must trust the brand they patronise before commitment can be sustained. When a customer have the confidence that a brand among its product category will effectively satisfy their need, and it does that over time, the consumer develops trust in such brand and commitment is built between them.

This implies that mere rebranding of a product may not generate equity but to generate trust and ensures consumers are committed to their brands, business owners must have strong awareness, positive association, strong perceived quality and high brand loyalty. Baalbaki and Guzman (2016) explain that brand equity stems from the greater confidence that consumers place in a brand than they do in its competitors. So, when consumers have greater trust in a brand than they do in its competitors, it builds, grows and sustain positive relationship between the brand and the consumers and this is generate frequent repurchase from the consumers for the brand. So, for brand owners and managers to generate loyalty from the consumers, they must create commitment and trust in them (American Marketing Association, 2015).

Rebranding

The term “brand” is conceptualised in two ways – the physical attributes of a product or the value embedded in a product. Faridah and Noor (2015) and Keller and Lehman (2004) define brand as the logo, the pictorial representation of the company and the signature of the company. Keller (2003) add that a brand is a name, term, sign, symbol or design or a combination of them used to identify the goods and services of one seller from that of the competitors. On the other hand, another set of scholars see brand as an intangible element, which serves as a valuable asset of an organisation contributing to greater value and market success (Wong & Merriless, 2007). In other words, a brand contributes immensely to the success of any organisation as it is the soul of operation of the business firm.

Rebranding occurs when a producer changes the physical attributes as well as perception of his product in the market (Muzellec & Lambkin, 2006). Every brand in the market is unique in the market. This uniqueness is determined by the physical elements of the product such as name, colour, catchphrase, size, scent, shape and others. Merriles and Miller (2008) explain that rebranding involves brand renewal, refreshment, makeover, reinvention, renaming and repositioning. This means that rebranding entails the process by which an existing product or service is modified to assume new identity and generate new perception in the minds of the consumers. Muzellec and Lambkin (2006) explains further that rebranding is a tool that comes handy when an organisation seeks to change consumer perception of his brand. So, rebranding can be said to be the modification of brand’s essential elements in order to reposition a product and also generate a new image. Daly and Moloney (2004) state that rebranding consists of changing some or all of the tangible (the physical parts of a brand) and intangible (value, image, and feelings) elements of a brand. The definition of this duo implies that rebranding can cover both the physical elements of a brand and the intangible aspects. The name, logo, colour, shape and other existing elements of a brand can be changed and rebranding a product can be aimed towards changing the value and the personality of the brand.

Muzellec and Stuart (2006) however identified that rebranding can be done in two ways: evolutionary or revolutionary. While evolutionary involves changing few elements of a brand, revolutionary entails a total overhauling of the entire brand elements. In the case of 9mobile, it was a revolutionary form of rebranding as all its brand elements were changed.

Consumer Based Brand Equity (CBBE)

There has been a long time debate on what equity actually stands for because brand equity is complex and multidimensional, involving various dimensions in other to measure the value a brand has for both the consumer and the owner (Aaker, 1991; de Oliviera et al, 2017). However, there have been two major approaches to the conceptualisation of equity (Raggio & Leone, 2007). The first approach to the conceptualisation of brand equity is seeing it as the value a brand has for both the consumers and the business owner. This is the commonly held conceptualisation of brand equity. According to Keller (2003) in Basar (2013:1), brand equity is determined by the measurable asset and liability of a good or service offer to the consumers. This implies that equity is the value consumers derive from consuming a particular brand and this value can increase or decrease. Similarly, Vazquez, et al (2002) conceptualise brand equity as total satisfaction consumers derive from consuming a brand. This definition still speaks to value of a brand to consumers and buttressing this, de Chernatony and McDonald (2003) position that brand equity is the overall satisfaction derived from a brand as compared to its competitors.

When a brand offers consumers expected utility, it adds value to the producer in term of increased patronage, referral, high sale and increase in the bottom line. This means that brand equity does not only add value to the consumers but also an organisation. This is why Shankar, Azar and Fuller (2008) aver that brand equity is determined by both the value it generates for consumers and financial value it accrues to the producer.

On the other hand, the second approach to the conceptualisation of brand equity is the position a brand occupies in the minds of the consumers. de Oliveira et al. (2015) submit that equity is determined from the standpoint of the consumers. According to Lins (2015), brand equity is the consumer assessment of a product and their attitude towards it the tool used to measure consumers’ attitude toward a brand. In a similar opinion, Keller and Lehmann (2004) see equity as the consumers’ attraction to or repulsion from a brand. This relates to how a consumer perceives a brand when it is mentioned. This is why Baalbaki (2012) states that one of the ways to measure brand equity is to first measure the brand awareness; this will create the opportunity to know the position of the brand in the market for the producer.

Putting the two approaches into perspective, brand equity is measured based on both consumer and financial measures (Shankar, Azar & Fuller, 2008). That is, brand equity is the value of a product to the consumers in terms of quality and satisfaction of needs and its financial value to the producer. Brands with high equity are great assets to their producers as consumers are always willing and ready to repurchase them. This makes it imperative for brand owners to seek ways by which they can increase their brands equity.

Having a high equity is advantageous to a brand and there is a strong association between brand preference and brand equity (Petburikul, 2009). Brand preference relates to choosing a product over its competitors and if the product continues to satisfy consumers need, it can generate trust, loyalty and equity. So, a brand with strong equity generates greater preference. It is also believed that a brand with strong equity influences consumers to pay premium prices, which they would not have paid for competing brands (Baalbaki & Guzman, 2016). When this happens, such brand becomes a though leader in its product category and stimulates more profits. This is so because the brand is perceived as of good quality, offers consumers more than what they expect, justify its market value, has positive positioning in the minds of the consumers, offers valuable utilities to both the consumers and the producer (Keller, 2002).

Dimensions of Consumer Based Brand Equity

There are various dimensions to a brand and it is believed that each of the dimensions is influenced by various factors such as culture, product category among others (Tong & Hawley, 2009). As averred by Olivera et al (2017), CBBE is built on interactions between various dimensions and each of the dimensions has different influence on the overall equity of a brand (Aaker, 1991). Sequel to this, there is no compromised reached on these dimensions by scholars (Oliveira et al, 2017). However, this study will adopt Aaker (1991) dimensions of Consumer Based brand Equity. The model has been widely used by scholars to examine brand equity in various sectors. Christodoulides and Chernatony (2010) submit that other dimensions of a brand aside the ones identified by Aaker (1991) are seen from the perceptive of an organisation but irrelevant to the consumers. Stuart and Muzellec (2004) note that a product does not just have a strong equity but with strong awareness, association, perceived quality and loyalty from the consumers. The brand equity dimensions identified by Aaker (1991) are brand awareness, association, perceived quality and loyalty.

Brand Awareness

Brand awareness is the first step to brand equity (de Oliviera et al., 2017). According to Basar, (2013), brand awareness is the ability of the consumers to recognise a brand and its elements. Consumers do not patronise a brand they know nothing about and this explains why promotion is one of the elements of brand marketing mix. Promotion informs, reminds and persuades the consumers to patronise a brand. This is why Baalbaki (2016) submits that the first step to building strong brand equity is through awareness. Awareness precedes association, purchase. A consumer who is not aware of a brand cannot ask for it in the market. That is, customers will not consider a brand if they are not aware of it (Tan, 2010). Huang and Sarigöllü (2012) state that brand awareness influence the performance of a brand in the market as it influences consumers’ buying decision.

Brand Association

Brand association refers to the connection of consumers have with a brand (Huang & Sarigöllü, 2012). It is the mental representation of a brand in the minds of the consumers and this representation (image) is born out of the awareness and knowledge consumers have with the brand. According to Basar (2013), the success of an organisation’s marketing strategies determines the association of such brand. Consumers’ association with a product is as a result of their contacts with it and these contacts can be through product experience, promotional activities (such as advertising) that are used to create, develop and sustain positive image for a brand in the consumers’ minds (Aaker, 1991). It is therefore important for brand producers to ensure that every point at which consumers make contact with their products create a favourable image in their minds.

Perceived quality

Aaker (1991) refers to perceived quality as the overall perception of consumers about the superiority of a brand over its competitors. Almost all products in the market have competing brands and the perceived quality of each of them relates to how consumers perceive them in term of their overall utilities. Basar (2013) says that perceived quality is the general quality or superiority of the brand compared to its competitors. As noted earlier, equity is regarded as the perception of consumers about a brand in term of utilities. The perception of the consumers about a product determines the success of the brand and this has bearing on the brand’s equity. It includes the customers’ judgment of the advantage, excellence, credibility and a brand difference compared to others (Satvati, Rabie & Rasoli, 2016). So, brand producers have to increase their brands’ quality with proper promotional mix to communicate the real quality of their brands to the consumers in order to increase their brand equity in the minds of the consumers. Aaker (1991) notes that a brand with strong perceived quality influences consumers’ patronage and their willingness to pay higher prices than for competing brands.

Brand Loyalty

The heart of brand equity is brand loyalty (Ballbaki & Guzman, 2016). Loyalty is a step towards equity and it is defined as the consumers’ commitment to a brand for continuous and unflinching patronage. This identifies that loyalty involves two dimensions – purchase and attachment. Baalbaki and Guzman (2016) explain that the awareness, association, perceived quality of a brand determine its loyalty. This perception may translate into repeat purchase which can translate to loyalty (Keller, 2003). Brand Loyalty is therefore related to a customer’s preference and attachment to a brand. It may occur due to a long history of using a product and trust that has developed as a consequence of the long usage. It is the deeply held commitment to re-buy or re-patronise a preferred product or service consistently in the future despite situational influences and marketing efforts having the potential to cause switching behaviour. It is the consumers’ dedication and determination to re-purchase a brand over and over again even when there are various marketing efforts by the brand’s competitors to make the consumer switch to them (Carroll & Ahuvia, 2006). Summarising the relevance of brand loyalty to equity, Ranjbariyan et al. (2012) submit that high brand loyalty leads to low cost of marketing, increases sales, attracts more customers/consumers and creates barriers to competitors.

Empirical review

Several studies have been conducted to examine the relevance of rebranding to the success of an organisation and the development of equity. Merillees and Miller (2008) conducted a study to examine the relevance of corporate rebranding strategy to brand equity. The study concluded that firms were not doing enough to maintain core values of building strong brands and consequently not maximising brand equity.

Basar (2013) also investigated if consumers’ perception of high brand equity affects brand extension. The study found out that brand equity had no effectiveness in internalizing brand extension. Petburikul (2009) also conducted a study on the impact of corporate re-branding on brand equity and firm performance. The results of the study showed that age, occupations, and economic status have effects on brand loyalty, perceived quality, brand awareness and brand association. Also, integrated marketing communication tools have impact on the brand dimensions. Pinar, Girard and Boyt (2010) investigated CBBE dimensions across the three types of banks in Turkey. They found out that the CBBE dimensions were significantly higher among private banks than the state and foreign counterparts because the private banks converted their brand awareness into patronage. Satvati, Rabie and Rasoli (2015) reported that there existed a relationship between brand equity and consumer behaviour, which includes paying premium price, brand preference and purchase intention. Caniago Suharyo, ZainulArifin and Kumadji (2014) in their study examined the effects of service quality and rebranding on brand image, customer satisfaction, brand equity and customer loyalty. The results show that the service quality significantly affects the brand image, customer satisfaction and brand equity. The researcher suggested that the better the equity of a brand, the better the customers’ loyalty towards the brand. This study will however investigate how rebranding has influenced the equity of 9mobile three years after the process was completed.

Methodology

This study adopted descriptive survey research design. It was adopted because it is good for examining people’s opinion and behaviour towards a brand and this study seeks to examine the opinion of subscribers of 9mobile. This research method also helps to standardise questions raised in a research and aids ease of coding and analysis (Wimmer & Dominic, 2011). This study population are 9mobile subscribers. The subscribers selected for this study were those who had subscribed to the network before it was rebranded from Etisalat Nigeria to 9mobile. This set of subscribers was selected because they were in best position to give relevant information about the brand before and after rebranding.

The study area is Abuja, the Federal Capital Territory (FCT). The FCT was selected because of its cosmopolitan nature and has a good number of 9mobile subscribers with various offices of the network provider there. Five hundred (500) subscribers were selected for the study using purposive sampling technique. The sampling technique was used because only subscribers who have been with the network providers were considered appropriate for this study. Therefore, subscribers who joined the network after it was rebranded were exempted from this study. Questionnaire was used to collect data from the subscribers. The questionnaire contains 18 Likert scale items used to collect data on the brand’s awareness/knowledge, image/association, perceived quality and loyalty. Out of the 500 copies of the questionnaire distributed; 440 were completed and retrieved; giving 88% return rate. The collected data were presented and analysed using frequency tables and Chi-Square.

Findings

The subscribers demographic profiles were first analysed before their responses to the items on the questionnaire were presented, analysed and discussed.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Respondents

| Variable | Frequency (n) | Percentage (%) | ||

| Age | 18-25 | 185 | 42 | |

| 26-35 | 130 | 30 | ||

| 36-45 | 81 | 18 | ||

| 46 above | 44 | 10 | ||

| Total | 440 | 100.0 | ||

| Gender | Male | 228 | 52 | |

| Female | 212 | 48 | ||

| Total | 440 | 100.0 | ||

| Occupation | Civil Servant | 113 | 26 | |

| Private Employee | 162 | 37 | ||

| Self Employed | 79 | 18 | ||

| Student | 49 | 11 | ||

| Retired | 37 | 8 | ||

| Total | 440 | 100.0 | ||

| Educational Status | Primary | 18 | 4 | |

| Secondary | 131 | 30 | ||

| Tertiary | 286 | 65 | ||

| No formal education | 5 | 1 | ||

| Total | 440 | 100.0 | ||

Note. Field, 2020

As shown in table 1, the respondents between ages 18-25 dominated this study and followed by those within the ages of 26-35. This indicates that majority of the respondents are the youth. Also, the two genders are well represented in this study but the males are slightly more than the females with just 4%. In addition, private employees dominated this study with 37%. The civil servants followed with 26% while the retirees were the least represented occupational group with just 8% of the total sample. Furthermore, 65% of the participants possessed tertiary education and just 5 (1%) participants did not have any formal education. This implies that a large majority of the subscribers of 9mobile in the FCT have advanced education

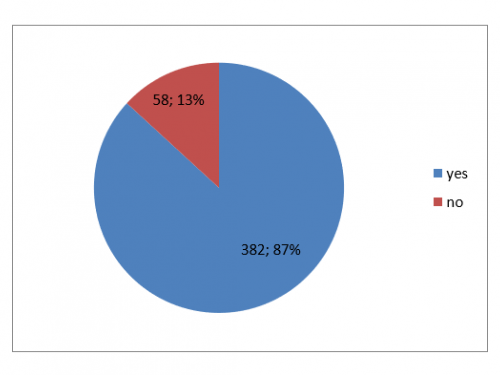

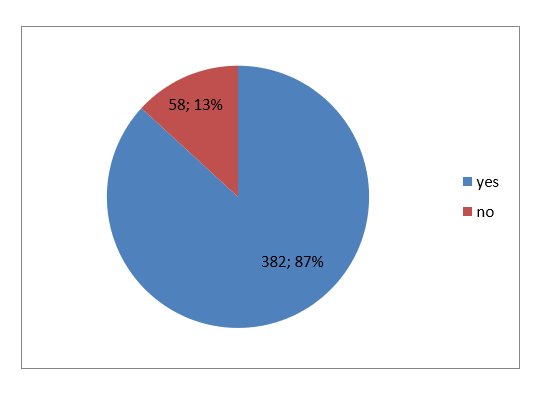

Figure 1.

Shows that most of the subscribers were aware of the rebranding process before 9mobile was rebranded.

Note. Fieldwork, 2020

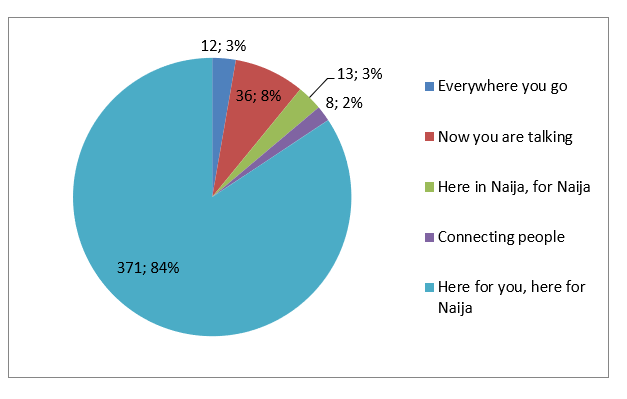

Figure 2.

The interpretation of 9mobile new slogan

Note. Fieldwork, 2020

As shown in figure 2, 84% of the subscribers are knowledgeable about the new catchphrase for 9mobile. This indicates that they are well familiar with the brand.

Table 2.

Extent of Subscribers’ Loyalty to 9mobile

| Items | SA(%) | A(%) | D(%) | SD(%) | UD(%) |

| I recognize 9mobile in comparison with the other competing products/brands when they appear on the media | 384(87) | 56(13) | – | – | – |

| 9mobile comes to my mind when I want make call/text | 230(52) | 97(22) | 64(14) | 33(8) | 16(4) |

| I can quickly recall symbol or logo of 9mobile when mentioned | 201(46) | 213(48) | 21(5) | 5(1) | – |

Note. Fieldwork, 2020

KEY: F=Frequency %= Percentage; SA=Strongly Agree, A=Agree, D=Disagree, SD=Strongly Disagree, UD=Undecided

Table 2 shows that all the respondents said they recognise 9mobile brand features. Also, majority of the subscribers (327, 74%) said 9mobile comes to their mind when there is need to make calls or text and most of them (414, 94%) said they quickly recall the symbols of 9mobile when mentioned.

With 87% awareness of the rebranding effort, 84% accurate answers for 9mobile catchphrase and the findings in table 4.2, it can be implied that 9mobile has a very strong awareness after the rebranding process and this can be attributed to the fact that the participants are 9mobile users

Table 3.

Influence of rebranding on 9mobile’s Association/image

| Items | SA(%) | A(%) | D(%) | SD(%) | UD(%) |

| 9mobile is committed to customer service | 48(11) | 198 (54) | 89(20) | 68(15) | 37(8) |

| 9mobile gives the best value for money | 70(16) | 134(30) | 89(20) | 6916 | 7818 |

| 9mobile is trust worthy | 215(48) | 104(24) | 51(12) | 49(11) | 21(5) |

| I easily remember the features of 9mobile | 272(62) | 140(32) | 22(5) | 6(1) | – |

| 9mobile is an appropriate brand for me | 72(17) | 191(43) | 89(20) | 78(18) | 10(2) |

Note. Fieldwork, 2020

KEY: F=Frequency %= Percentage; SA=Strongly Agree, A=Agree, D=Disagree, SD=Strongly Disagree, UD=Undecided***

Awareness precedes association and contact with brand determines the image of a brand. With findings in table 3, it can be deduced that 9mobile has high positive image in the minds of the subscribers. This is determined by 65% agreement to the brand’s commitment to customer service, 72% trustworthiness, 94% recall rate and 60% agreement to the brand being appropriate. However, only 46% of the subscribers agreed that 9mobile gives the best value for money. With 67% average agreement rate, we conclude that 9mobile has high brand association among Abuja subscribers after rebranding.

Table 4.

Subscribers perceived quality of 9mobile after rebranding

| Items | SA(%) | A(%) | D(%) | SD(%) | UD(%) |

| 9mobile gives individual customer attention | 51(12) | 187(43) | 65(14) | 46(15) | 91(21) |

| I prefer the way 9mobile handles customer complaint to other telecoms providers | 147(33) | 64(15) | 74(17) | 68(15) | 87(20) |

| I prefer 9mobile because the call charge is relatively cheap | 74(17) | 121(28) | 111(25) | 56(13) | 78(17) |

| I prefer 9mobile because of it fast browsing network | 71(16) | 175(40) | 98(22) | 40(19) | 56(13) |

| I use 9mobile more than other network providers because of its quality of services | 41(9) | 187(43) | 87(20) | 47(11) | 78(17) |

Note. Fieldwork, 2020

KEY: F=Frequency %= Percentage; SA=Strongly Agree, A=Agree, D=Disagree, SD=Strongly Disagree, UD=Undecided***

Data presented in table 4 shows that the subscribers have an average perceived quality for 9mobile after it was rebranded. Only average of the respondents agreed that it gives individual customer attention (53%), has fast browsing network (56%) and they use 9mobile because of its service quality (51%) while below average of the subscribers agreed that 9mobile has cheap call rate (45%) and prefer how it handles customer complaint (48%). With an average agreement percentage of 50.6%, it is concluded that 9mobile has an average perceived quality after rebranding.

Table 5.

Extent of Subscribers’ Association with 9mobile

| Items | SA(%) | A(%) | D(%) | SD(%) | UD(%) |

| 9mobile has become the first choice of telecom brand for me | 57(13) | 140(32) | 87(20) | 81(18) | 75(17) |

| I regularly recommend 9mobile to other people | 71(16) | 185(42) | 92(21) | 57(13) | 35(8) |

| I will not switch to another telecom brand | 22(5) | 197(45) | 142(32) | 69(16) | 10(2) |

| I recharge my line more after rebranding than I did before rebranding | 100(22) | 148(34) | 80(18) | 79(18) | 34(8) |

| I am committed to 9mobile | 68(15) | 177(40) | 121(28) | 45(10) | 29(7) |

Note. Fieldwork, 2020

KEY: F=Frequency %= Percentage; SA=Strongly Agree, A=Agree, D=Disagree, SD=Strongly Disagree, UD=Undecided***

Data presented in table 5 shows that brand loyalty for 9mobile is average. This is unconnected from the average perceived quality found previously. Equity is regarded as perception and this perception affects brand equity (Lin, 2015). The table above shows that below half of the respondents agreed that 9mobile is their first choice of brand (45%), 58% agreed that they recommended 9mobile to other people, half (50%) said they would not switch to other telecoms brand, 54% recharge more after rebranding while 55% said they are committed to 9mobile. With average agreement rate of 52.4%, it can be inferred that 9mobile has moderate brand loyalty among its subscribers after rebranding.

In order to determine the significant influence of rebranding on CBBE dimensions of 9mobile, a test of significance was carried out to test how awareness of 9mobile rebranding process affects its association, perceived quality and loyalty, with pre-defined significance level of 0.05. From the results presented in table 6, it is shown that rebranding awareness only has significant effect on brand association but not on perceived quality and brand loyalty.

Table 6

Test for significance

| Chi-square | P-value | Decision |

| Brand Association | 0.003 | Significant |

| Perceived quality | 0.921 | Insignificant |

| Brand loyalty | 0.876 | Insignificant |

Significant level: 0.05

Note. Fieldwork, 2020

Discussion

Data analysis and interpretation has revealed that majority of the respondents were aware of the rebranding process of 9mobile and most of them were able to recall the brand’s new catchphrase. Based on the Aaker’s (1991) CBBE model, the first step to ensuring strong brand equity is brand awareness and it precedes association and purchase (Baalbaki, 2016). This finding shows that the brand properly handled its first dimension of equity.

It was also revealed that the brand has a high brand association level among Abuja subscribers after rebranding. This is owned to the fact that consumers are able to establish certain links with the brand. With a very high awareness level and high association, this finding aligns with the position of Keller (2003) that for consumer’s association with a brand to have a positive effect on brand equity, they must be unique, strong and favourable. Vazquez, et al. (2002) add that brand equity as the overall utility that the consumer associates with the use and consumption of the brand; including associations expressing both functional and symbolic utilities.

On perceived quality, it was however revealed that the consumer perception of 9mobile in term of quality is average. For a brand to have strong equity, its perceived quality must be strong as well. This finding implies that 9mobile has no significant influence on 9mobile equity. This negates the findings of Saleeh (2016) that rebranding has a positive significant effect on the quality of products (Saleh, 2016). It therefore confirms the finding of Osei-Wusu (2016) that rebranding has no impact on perceived quality and customer satisfaction.

Lastly, it was found that rebranding has a moderate influence on brand loyalty for 9mobile. Consumer perception of a brand affects their trust and commitment to the product and when perceived quality is low, loyalty is also expected to be low. In the case of 9mobile, the influence on perceived quality and loyalty is average. Further analysis revealed that rebranding has significant influence on 9mobile brand association but no significant relationship was found with perceived quality and brand loyalty. This result is confirmed by the latest subscribers statistics in Nigeria as 9mobile still remains number four behind MTN, Glo and Airtel with about 12 million subscribers as at second quarter of 2020 but had over 13 million subscribers in 2019 (Nigerian Communications Commission, 2020). This shows that the telecommunication company still maintains the position it was before it was rebranded.

This finding confirms that rebranding has no moderating effect between service quality and brand loyalty (Bamfo, et al, 2018) and no influence on brand equity (M’Sallem et al., 2009).

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this study, it can be inferred that rebranding of 9mobile has no significant relationship on its brand equity. A brand cannot generate high equity with low perception, little commitment and loyalty from consumers. It is however recommended that the brand focuses on improving its service quality, customer relationship and satisfaction. Consumers patronise the brands they trust and trust breeds commitment/loyalty (Morgan & Hunt (1994). Trust, according to Phillips (2015), is earned through continuous satisfaction of consumers in open and transparent manners. As such, the brand equity will increase and become strong.

Author: BABATUNDE C. AKINSOLA

References

Aaker, D. J. (2000). “Brand Leadership”, Free Press, New York.

Alshebil, S. A. (2007). Consumer Perceptions of Rebranding: The Case of Logo Changes. A PhD thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Arlington.

American Marketing Association (2015). The Commitment-Trust Theory. Journal of Marketing Management, Vol. 3, No. 1

Baalbaki, S. (2012), Consumer Perception of Brand Equity Measurement: A New Scale (Doctoral dissertation), Denton: Texas. UNT Digital Library. http://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc115043/.

Baalbaki, S. & Guzman, F. (2016). Consumer-Bassed Brand Equity. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/309478932

Bamfo, B. A., Dogbe, C. S. & Osei-Wusu, C. (2018). The effects of corporate rebranding on customer satisfaction and loyalty: Empirical evidence from the Ghanaian banking industry. Cogent Business & Management (2018), 5: 1413970. Available at https://doi.org/10.1080/23311975.2017.1413970

Basar, E. E. (2013). The Effects of Consumers’ Brand Equity Perceptions on Brand Extension Strategy. Available at https://www.researchgate.net/publication/264037642

Caniago, A., Suharyono, ZainulArifin & Srikandi Kumadji, S. (2014). The Effects of Service Quality and Corporate Rebranding on Brand Image, Customer Satisfaction, Brand Equity and Customer Loyalty (Study in Advertising Company at tvOne). European Journal of Business and Management, Vol.6, No.19, 2014

Carroll, B. A. & Ahuvia, A. C. (2006). Some antecedents and outcomes of brand love. Marketing Letters. Vol. 17(2), 79-89.

Christodoulides, G., & Chernatony, L. de. (2010). Consumer-based Brand Equity Conceptualization and Measurement: a literature review. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 52(1), 43–66.

Daly, A. and Moloney, D. (2004). Managing Corporate Rebranding,” Irish Marketing Review, vol. 17, no. 1/2, 2004, pp. 30-36.

De Chernatony, L. and McDonald. M. (2003). Creating Powerful Brands, Elsevier, Butterworth: Heinemann.

De Oliveira, D. S., Caetano, M. & Coehlho, R. L. (2017), Approaches that affect consumer-based brand equity Revista Brasileira de Marketing, vol. 16, núm. 3, julio-septiembre, 2017, pp. 281-297, Universidade Nove de Julho, São Paulo, BrasilBrazilian Journal of Marketing

Faridah, I. & Noor, H. (2015). A Review of the Literature on Brand Loyalty and Customer Loyalty. Universiti Utara Malaysia Sintok, Kedah

Gikonyo, C. N. (2016). Influence of rebranding on customer perceptions: a case of National Bank of Kenya. A research project submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Science In Marketing School of Business, University of Nairobi

Huang, R., & Sarigöllü, E. (2012).How Brand Awareness relates to Market Outcome, Brand Equity, and the Marketing Mix. Journal of Business Research, 65(1), 92–99.Keller, K., L. (2003). Strategic Brand Management: Building. Measuring and Managing Brand Equity. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Keller, K. L. & Lehmann, D. R. (2004) Brands and Branding: Research Findings and Future Priorities. Paper presented at Marketing Science Institute Research generation Conference and 2004 AMA Doctoral Consortium

Lin, Y.H. (2015). Innovative brand experience’s influence on brand equity and brand satisfaction, Journal of Business Research, JBR-08423. Available at http://www.researchgate.net/publication/282621001_Innovative_brand_experience’s_influence_on_brand_equity_and_brand_satisfaction

Mack, S. (2014). The Commitment-Trust Theory of Relationship Marketing. Available at http://smallbusiness.chron.com/commitmenttrust-theory-relationship-marketing-65393.html

Merrilees and Miller (2008). Principles of corporate Rebranding. European Journal of Marketing DOI: 10.1108/03090560810862499 · Source: OAI· May 2008

Morgan, R.M., & Hunt, S.D. (1994). The commitment-trust theory of relationship marketing. Journal of Marketing. Vol. 58(3), 20–38.

M’Sallem, W., Mzoughi, N. & Bouhlel, O. (2009). Customers’ evaluations after a bank renaming: effects of brand name change on brand personality, brand attitudes and customers’ satisfaction. Innovative Marketing, 5(3)

Muzellec, L. , Doogan, M. & Lambkin, M. 2003. Corporate rebranding – an exploratory review. Irish Marketing Review, 16, 2, pp. 31-40. Library. E-resources. Electronic periodicals and articles. Abi Inform: Proquest Direct. URL: http://www.haaga-helia.fi/en. Accessed: 12 Apr 2012.

Muzellec, L. & Lambkin, M. (2006). “Corporate Rebranding: Destroying, Transferring or Creating Brand Equity.” European Journal of Marketing, 2006: 803-824. Available at http://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/full/10.1108/03090560610670007

Mwangi, G. G. (2013). The influence of strategic corporate re-branding on customer satisfaction among mobile service providers in Kenya. A research project submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Master of Business Administration Degree of the School of Business, University of Nairobi

National Bureau of Statistics (2018) Telecoms Data: Active Voice and Internet per State, Porting and Tariff Information. Abuja

Nigerian Communications Commission (2020). Subscriber statistics. Available at www.ncc.gov.ng/statistics-reports/subscriber-data

Osei-wusu, C. (2016). The interrelationships between corporate rebranding, perceived service quality, customer satisfaction and customer loyalty. The case of GCB Bank Limited, thesis submitted to the department of marketing and corporate strategy, Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Business Administration (marketing option).

Petburikul, K. (2009). The Impact of Corporate Re-branding on Brand Equity and Firm Performance. Ramkhamhaeng University International Journal. Vol. 3(1), 2009. Available at http://www.citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewoc/download;jsessionid=E20C71D31A8332A6BB2C60544C