The Internationalization of Higher Education in Canada: International Students as a Source of Skilled Labour Supply

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada recently implemented an entry system based on obtaining a student visa. In search of a better life and promised permanent residency (PR) after graduation, the number of international students using this pathway has increased dramatically. Their participation in the Canadian labour force (while studying) is pivotal to this system. This paper uses an integrative literature review research methodology to examine the impact of these trends on the Canadian labour market and economy. We also look at the challenges and opportunities associated with the internationalization of higher education in Canada, specific to the Canadian labour market.

Over the past few decades, many multifactorial causes can be attributed to the rise in international students’ numbers in Canada. Those which have been studied most in-depth (Crossman et al., 2022a; El-Assal, 2020; Garson, 2016) include Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) policies and regulations, global trends in the internationalization of higher education, increased access to communication technologies, and globalization more generally. In concert together, these factors in particular combine in ways which have made Canada a destination of choice for international student recruitment. This has had complex and wide-ranging effects on international students themselves (Naji, 2023) but the policy emphasis which drove these shifts was focused on maximizing profit margins. One policy change in particular was made by the Canadian government in 2014: its International Education Strategy revised its international student program regulations with the specific intention of doubling the number of international students by 2022 (Government of Canada, 2014). In response to this policy shift, educational institutions also had to adapt their policies and regulations to ensure they maintained alignment with those broader policy shifts (Buckner et al., 2020).

These policy shifts also included certain restrictions on the kind of work (quality) that international students could do, and the number of hours (quantity) they could work, generally calculated as a weekly cap. Further, they required international students to bank a certain number of hours of work experience in order to qualify for permanent residency status. It is these policies that relate most specifically to the Canadian government’s policy direction which perceives international students as an additional source of labour. International students do benefit from acquiring work experience in Canada and the income earned from their labour. However, the revenue generated by their labour (in terms of taxable income) benefits the Canadian government in far greater proportion. This is particularly true in the case of international students because their education (the acquisition of skills in their ‘skilled labour’) is not subsidized by either the Canadian government or educational institutions; they are paying the full cost of their tuition. Even further, international students are often willing (and/or pressured by financial stress brought on by paying steep tuition fees and high cost-of-living expenses) to take on jobs outside their field of study in order to gain necessary work experience.

The policies which structure their employment conditions create ‘flexibility’ in the labour force, which may benefit the low-wage sector but create precarity for workers. Garson (2016) argues that using international students as a strategy to generate revenue or labour is problematic, but the reality that Trilokekar and El Masri (2019) present is one in which policies which internationalize higher education in Canada have been shifting in those directions since the 1960s. These historical developments have culminated in the present situation and therefore it is important to study the internationalization of higher education and these changes, nationally and globally. This study aims to contribute to that body of knowledge and the researcher’s interest in the field is both personal, in that she has a passion for lifelong learning and is herself an international student, and professional in that she works with international students in higher education. It is also humanitarian in that the author feels responsible for providing support to international students on their journeys.

Consequently, the following integrative literature review first discusses the context of the internationalization of higher education with regard to international students and then examines how the skilled labour of international students contributes to the Canadian labour market. Following that review is a discussion which synthesizes that research and provides a set of recommendations before concluding.

Integrative Literature Review

The Internationalization of Higher Education and International Students

Knight (2015) defines internationalization as the sharing of international programs and education, while De Wit (2019) defines the internationalization of higher education as teaching and learning opportunities which are offered internationally. Özler (2013) defines it as the globalization of higher education and understands it as a tool for connecting people on cultural and political levels. Research has also shown that the internationalization of higher education produces increased revenue and sources of labour (Crossman et al., 2021; Guo & Guo, 2017; Reilly, 2020; Williams et al., 2015) and some research (Knight, 2015) includes educational institutions in this, because of their interest in generating increased revenue.

Since 2000, the Canadian government has used immigration-friendly policies to recruit future immigrants (Trilokekar & El Masri, 2019) and to market Canada as a popular destination for international students to study, work and live (Crossman et al., 2022a). This strategy has been effective. Citizenship and Immigration (2021a) indicates that worldwide, Canada is the fourth most popular destination for international students. International students choose Canada for many reasons; the ‘study, work and stay’ model of policy significantly enhances the attractiveness of this option.

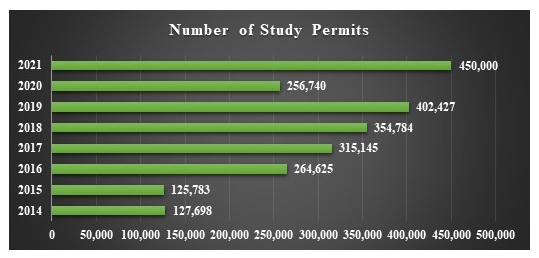

This is also an attractive policy option for generating revenue for governments and educational institutions, in two streams: higher tuition fees and generating an influx of unsubsidized skilled labour into the Canadian labour market. However, these policy shifts originated at a time when enrolment was low: this move was a response to that, as well as to governments’ cutbacks to higher education which forced educational institutions to look for other sources of revenue. The implementation of this policy not only changed that one factor (enrolment numbers) but had significant repercussions in other areas, many of which were unforeseen and remain unaccounted for (including the well-being of international students themselves). The number of international students has increased dramatically. According to the Government of Canada (2022a), the number of study permits issued to international students between 2014-2021 has surged from 127,698 (in 2014 when the policy change occurred) to about 450,000 in 2021 (except in 2020 due to the pandemic). See Figure 1 below for a visual representation of this trend.

Figure 1

Number of Study Permits

Note: The information was collected from the Annual Reports to Parliament on Immigration (the number of international students as per their study permits) from 2014 to 2021. Adapted from the Government of Canada (2022a).

The same report (Government of Canada, 2022a) indicated that the revenue increased (2014-2021) from about $8 billion in 2014 to $20 billion in 2021. According to the Canadian Bureau for International Education (2022) international enrollment has increased by 43% in the last five years (between 2016 to 2021). The report also states that in terms of the short-term future, 72.5% of international students plan to apply for work permits and about 60% plan to apply for permanent residency after completing their education.

According to Kim and Kwak (2019) international students in countries such as Canada, Australia, and the United Kingdom contribute billions of dollars per year to the economies of those countries, thus the internationalization of higher education appears to have more to do with generating revenue, meeting labour market demands, increasing population rates, and recruiting skilled workers than with enhancing the educational experience for students or meeting their needs as students and workers. However, McCartney (2020) argues that this is not a new phenomenon and that educational institutions and governments have always treated international students as objects to serve their purposes.

Only recently Ontario colleges have recognized that in the matrix of internationalized higher education, international students deserve more support in exchange for the value they are creating for educational institutions and the labour market. In a recent announcement, they stated that programs offered in Ontario colleges need to be strengthened through the creation of standards, and the provision of support for international students (Ontario Colleges, 2023)., however, there is still a long way to go.

The Internationalization of Higher Education and the Canadian Labour Market

The internationalization of higher education has contributed significantly to the labour market, if only in terms of numbers (although the full reality of their contribution is far greater and more complex). The number of international students has increased rapidly since 2014, and Canada, with an aging population, low birth rate, and struggle to fill positions in certain sectors of the labour market, needs migrants to remain sustainable. How sustainable are the working lives of migrants (including the working lives of international students), however, is a question that is not asked enough. Therefore, recruiting international students is the most effective way to overcome those needs.

Recruiting international students is seen as a means of holding up the labour force in the areas where it can be difficult to retain domestic Canadian workers, arguably in a similar way as educational institutions relied on international students to help curb low enrolment rates. The Government of Canada’s strategic planning (2019-2024) specifically mentions the contribution of international students to the labour market and the Canadian economy, seeking to “draw students from around the world to communities across Canada where they can enrol in a wide variety of schools and programs at all educational levels [by ensuring that] Canada’s labour force has the needed skills and talents” (Government of Canada, 2019, p.3). In this document, the policy mentions graduate students specifically as an important source of talent and source of skilled labour in the context of Canada’s aging population.

What does ‘skilled labour’ in the context of international students look like? As one example, international students arrive in Canada already having a set of skills which increase their employability in the skilled labour market. This includes proficiency in one of Canada’s official languages, prior education, and a higher probability of prior work experience. In the process of obtaining a Canadian education, international students apply for a temporary work permit which enables them to participate in the labour force and gain Canadian work experience. This in turn opens the pathway to applying for and obtaining permanent residency status, which may eventually lead to Canadian citizenship if they continue to successfully meet the required criteria for these legal status categories.

This is also known as a three-step education migration process, which as described by Brunner (2022) includes three iterations of personhood as defined by three separate legal categorizations: the student (who is only authorized to work part-time), the temporary foreign worker (who is authorized to work at any job except for sex and sex-related work), and the permanent resident (who must meet residency criteria). According to Guo and Guo (2017) policies such as these allow international students to participate in the labour market and generate revenue quickly. Under the same policies, international students can work up to 20 hours per week on or off campus to gain income, work experience, and participate in the labour market.

Although stringent and intensive, this pathway to Canadian permanent residency and/or citizenship is nevertheless an attractive option for many new immigrants. It allows them to better integrate into Canadian society and to take advantage of the many benefits of Canadian citizenship. These opportunities mainly happened as a result of the 2014-2019 International Education Strategy (Government of Canada, 2014). The same strategy viewed international students as a source of skilled labour supply (Government of Canada, 2014).

There are other pathways as well. As described by Reitz (2020), one more recent immigration program is the Canada Experience Class, which offers permanent residency to eligible candidates who already have Canadian work experience. In addition, in response to vastly increased labour market needs (because of the recent Covid-19 pandemic), the Canadian government temporarily revised its permanent residency policy and provided permanent residency to 40,000 international graduate students (Citizenship and Immigration, 2021a).

Note: The combination of credentials, knowledge, skills, and work experience (Government of Canada, 2021b). https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/campaigns/study-work-stay.html

However, as McCartney (2020) points out, something is missing from the government’s strategic planning and programs and that is a focus on the quality of education. What has replaced this focus is a shift in how international students are perceived. His work also points out the dichotomy between previous policies and the current ones. Prior to 2014, the implicit understanding on the part of policies on international students was that they should obtain a Canadian education so that they could return to their home country, contribute to that economy, and labour market. In more recent policies (since 2014) this has been revised such that they now encourage students to stay in Canada (McCartney, 2020) and contribute to the Canadian economy and labour market. Overall, this reflects a view that international students’ skilled labour (and the skill they specifically obtain because of a Canadian education) is a marketable commodity that is primarily of use to the economy and labour market. More recently, since Canada has more need for skilled labour, the marketing emphasis reflects a push for international students to stay, work and live here. In other words, international students have been reviewed as commodities that serve their purposes. International students are seen as a valuable source of labour that can be used to fill jobs in Canada, and so the current policy landscape reflects that.

Crossman et al. (2022b) argue that international students do in fact substantially support Canadian labour market needs during and after their education. In one study, Crossman et al. show an increase in labour participation of international students by documenting how their earnings doubled from $14,500 in 2008 to $26,800 in 2018 (Crossman et al., 2022b, p.8). These changes in policies continue to shift in favour of what will most benefit the needs of the Canadian labour market. More recently for example, IRCC announced in October 2022 that because of the challenges the labour market is experiencing in the recruitment and retention of employees, they would be temporarily lifting the weekly cap (20 hours) on the number of hours international students are permitted to work (Government of Canada, 2022b). This announcement used language which implied that these temporary changes would benefit international students and graduates while providing greater employment and work experience opportunities. It also acknowledged the importance of international students’ labour to meet the shifting challenges of the labour market, including labour shortages (Government of Canada, 2022b).

Discussion and Recommendations

A common distinction (both legally and in immigration discourse) is made between people who migrate to obtain economic, social, and political freedom and people who migrate to gain employment, economic, and social opportunities. The reality for many migrants (including international students is not as clear-cut as these legal categorizations would suggest). International students are in search of better opportunities, and they pursue these by seeking an international education and international employment opportunities. Their contribution to the Canadian economy and labour market is increasingly invaluable and necessary in sustaining those institutions, both in terms of higher tuition fees and in terms of their availability as a source of skilled labour. However, there has always been a tension between the needs of employers and the needs of employees in the labour market and international students’ needs both as students and as skilled workers, deserve consideration and study. According to McGregor et al, (2022) there is a gap in the literature when it comes to how international fare after graduation.

As has been shown above, the numbers of international students have increased dramatically and so there are more ‘payers of higher tuition’ in the absolute. Thus, international students pay at least three times as much tuition (in terms of a dollar amount) than domestic students. Even if the government and higher educational institutions had lowered the cost of tuition for international students so that it was more affordable, they would have still generated revenue, because the number of international students has increased. However, this was not the case. In essence, there were more students (as a whole), each paying more tuition (individually). Arguably, the internationalization of higher education in Canada is no longer about filling a gap left by education cutbacks; it is about creating a multi-institutional industry (higher education, immigration, and labour) which is using the tuition fees and labour of international students to kick profits into high gear and keep them there. This shift has not come without consequences.

According to Garson (2016), a model of education which operates mainly for profit can be problematic in itself. As well, overlooking the difficulties and needs faced by international students before, during and after their migration is also problematic. There is ample research which demonstrates that post-secondary students (in general) are at a higher risk of stress (Clough et al., 2019; Shadowen et al., 2019). Richardson et al.’s (2017) work also demonstrates the direct relationship between financial difficulties, stress, and physical health. Certainly, international students face compounded stressors (including financial stress). Their contributions to the economy and labour market deserve to be met with consideration of their rights as people living in Canada who are part of our communities, schools, and workplaces. Their well-being matters.

The following recommendations should be considered by stakeholders in the education, immigration, and labour sectors in order to maintain the sustainability of international students’ working lives as skilled workers whose contribution to those sectors should be valued in concrete ways which directly benefit their well-being and success.

- It is vital to conduct more research regarding the well-being of international students in the labour market (as well as within educational institutions) to better understand their challenges, needs and successes challenges, and support them in a constructive way. The research should consider the long-term consequences of international students’ place in the labour market, their physical and mental health and ultimately their well-being.

- The quality-of-life factor should not be minimized in policies concerning international students. Taking this factor into account will lead to compounded improvements in health, well-being, human development, and socioeconomic status, promoting sustainable economic growth.

- It is imperative to encourage international students to voice their opinions without negative consequences and consider their input and experiences when developing policy.

- Services and programs should be student-centred and consider students’ needs and rights, both collectively and individually. Otherwise, policies will continue to be discriminatory and racist and lead to inequality and marginalization from the market.

- Students should be supported in accessing and obtaining skilled or professional employment in their field of study. According to the Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD), under-employment, inadequate quality employment, and unemployment have a negative impact on human psychological health (2012) which should be avoided.

- International students should be supported at all stages of their transition: before, during and after their migration to an unfamiliar environment. This includes migration to a new country, new educational institution, and a new and unfamiliar labour market with (often) vastly different laws around employment, work, and organizational cultures, etc.

- Finally, general awareness and knowledge around rights and responsibilities, equality, integrity, holding open dialogues, and support should be integrated into sectors of the labour market which employ international students. This not only benefits international students but will have a beneficial effect on the health of the labour market and workers in general.

It is also important to acknowledge the ways in which the Government of Canada and educational institutions are moving toward improving support for international students, including in their skilled work in the labour market. As part of this paper, the author reviewed how (for example) Ontario colleges in Canada are focusing on improving the quality of international students’ education and experiences by considering their needs through strategic planning. There are small steps being taken toward a better future and it is imperative to implement and manage these initiatives to better serve international students and this is most effectively done by listening to international students themselves, including their perspectives on their experience as skilled workers in the labour market.

Conclusion

The intention of this paper was to contribute new knowledge about international students as a source of skilled labour in the Canadian labour market, a topic which is understudied in the fields related to education and immigration. Thus, this author sought to answer two questions:

- How does the internationalization of higher education affect international students as a source of skilled labour?

- How does the internationalization of higher education impact the Canadian labour market and economy?

The integrative review was used as a research methodology. Which was especially suited to answering this complex and wide-ranging issue. While conducting this review, a few aspects of this specific concern were noticed.

- The policies and programs implemented in response to the internationalization of higher education have been changing over the past few decades, particularly since 2014.

- Strategic planning, policies, and programs have been responsible for a dramatic increase in the number of international students in Canada and this has had significant effects on the education sector and the labour market.

- The increasing numbers and higher tuition fees paid by international students have generated increased revenue, especially since their education is not subsidized and the selection criteria privileges entrants who already hold highly marketable skills in the Canadian economy.

- Their existing skills, education, ability to pay fees and ‘mandatory flexibility’ as workers who are forced to adapt to the changing needs of the labour market are leveraged to serve the needs of the labour market.

As international students increase, so does the number of skilled labour workers. Their contribution to the labour market parallels their contribution to the educational sector. This follows the government cutbacks which drove the first push to internationalize higher education in Canada before 2014. This has positive effects on the lives of international students. Almost three-quarters of international students obtained permanent residency within five years of obtaining their post-graduate work permit (Crossman et al., 2022b). Thus, having access to these labour market opportunities makes the transition possible or more accessible in terms of gaining economic advantages.

This pathway to facilitating better lives for international students is a worthwhile goal. Also, it is vital that the stakeholders involved in higher education, immigration and the labour market hold a proper perception of international students. Treat the international students as people, not as products or commodities. As well as it is important to consider that international students are not only students; they are also workers (and very often skilled workers).

References

Buckner, E., Clerk, S., Marroquin, A., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Strategic benefits, symbolic commitments: How Canadian colleges and universities frame internationalization. Canadian Journal of Higher Education/Revue canadienne d’enseignement supérieur, 50(4), 20-36.

Canadian Bureau for International Education. (2022). Retrieved from: https://cbie.ca/infographic/

Clough, D. R., Fang, T. P., Vissa, B., & Wu, A. (2019). Turning lead into gold: How do entrepreneurs mobilize resources to exploit opportunities? Academy of Management Annals, 13(1), 240-271.

Crossman, E., Choi, Y., & Hou, F. (2021). IS as a source of labour supply: The growing number of IS and their changing sociodemographic characteristics. Statistics Canada. IS as a source of labour supply: The growing number of IS and their changing sociodemographic characteristics (statcan.gc.ca).

Crossman, E., Choi, Y., Lu, Y. & Hou, F. (2022a). IS as a source of labour supply: A summary of recent trends. Statistics Canada. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/36-28-0001/2022003/article/00001-eng.pdf?st=HUB5WtCQ

Crossman, E., Lu, Y., & Hou, F. (2022b). International students as a source of labour supply: Engagement in the labour market after graduation. Statistics Canada= Statistique Canada.

De Wit, H. (2019). Evolving concepts, trends, and challenges in the internationalization of higher education in the world. Вопросы образования, (2 (eng)), 8-34.

El-Assal, K. (2020). International Students. CIC News. 642,000 international students: Canada now ranks 3rd globally in foreign student attraction. https://www.cicnews.com/2020/02/642000-international-students-canada-now-ranks-3rd-globally-in-foreign-student-attraction-0213763.html

Garson, K. (2016). Reframing internationalization. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 46(2), 19-39.

Government of Canada. (2014). “Immigration and Refugee Protection Act: Regulations Amending the Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations.” Canada Gazette Part II, 148 (4). Available at: https://gazette.gc.ca/rp-pr/p2/2014/2014-02-12/html/sor-dors14-eng.html.

Government of Canada. (2019). Building on Success: International Education Strategy 2019 – 2024 https://www.international.gc.ca/education/assets/pdfs/ies-sei/Building-on-Success-International-Education-Strategy-2019-2024.pdf

Government of Canada. (2021a). Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. CIMM-International Students- June 2, 2021. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/transparency/committees/cimm-jun-02-2021/international-students.html

Government of Canada. (2021b). Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Stay in Canada after you graduate. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/campaigns/study-work-stay.html

Government of Canada. (2022a). Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Departmental Plan 2022-2023. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/corporate/publications-manuals/departmental-plan-2022-2023/departmental-plan.html#s32

Government of Canada. (2022b). Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada. International students to help address Canada’s labour shortage. https://www.canada.ca/en/immigration-refugees-citizenship/news/2022/10/international-students-to-help-address-canadas-labour-shortage.html

Guo, Y., & Guo, S. (2017). Internationalization of Canadian higher education: Discrepancies between policies and international student experiences. Studies in Higher Education, 42(5), 851-868.

Kim, A., & Kwak, M. J. (2019). Outward and upward mobilities: International students in Canada, their families, and structuring institutions. University of Toronto Press.

Knight, J. (2004). Internationalization Remodeled: Definition, Approaches, and Rationales. Journal of Studies in International Education, 8(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315303260832

Knight, J. (2015). Updated definition of internationalization. International Higher Education, (33). Retrieved from http://ejournals.bc.edu/ojs/index.php/ihe/article/viewFile/7391/6588

McCartney, D. M. (2020). From “friendly relations” to differential fees: A history of international student policy in Canada since World War II (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia).

McGregor, A., Decarie, C., Whitehead, W., & Aylesworth-Spink, S. (2022). Supporting international students in an Ontario college: A case for multiple interventions. The Canadian Journal of Action Research, 22(2), 5-28.

Naji, M. (2023). Examining the Educational Experiences of International Students in Ontario, Canada-Implications for Post-Secondary Management Practice [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. LIGS University.

Ontario Colleges (2023). Ontario Public Colleges’ Standards of Practice for International Education. https://cdn.agilitycms.com/colleges-ontario/documents-library/document-files/International%20standards%20-%20March%202023_20230314184657_0.pdf

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (2012). Sick on the job?: myths and realities about mental health and work (pp. 199-210). Paris, France: OECD publishing.

Özler, Ş. İ. (2013). Global citizenship versus diplomacy: Internationalisation of higher education with a collective consciousness. Weaving the future of global partnerships, 13-18.

Reichert, P. (2020). Internationalization & career-focused programming for international students: a qualitative study of universities in Canada.

Reilly, S. E. (2020). Conceptualizations of the international student in international migration law, diplomacy, and higher education economy: A transatlantic perspective.

Shadowen, N. (2019). Ethics and bias in machine learning: A technical study of what makes us “good”. In The Transhumanism Handbook (pp. 247-261). Springer, Cham.

Sharipov, F. (2020). Internationalization of higher education: definition and description. Mental Enlightenment Scientific-Methodological Journal, 2020(1), 127-138.

Toronto, C. E., & Remington, R. (Eds.). (2020). A step-by-step guide to conducting an integrative review (pp. 1-9). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Torraco, R. J. (2005). Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Human resource development review, 4(3), 356-367.

Trilokekar, R. D., & El Masri, A. (2019). Golden”: Canada’s Changing Policy Contexts, Approaches, and National. Outward and upward mobilities: International students in Canada, their families, and structuring institutions, 25.

Williams, K., Williams, G., Arbuckle, A., Walton-Roberts, M., & Hennebry, J. (2015). International students in Ontario’s postsecondary education system, 2000-2012: An evaluation of changing policies, populations and labour market entry processes. Higher Education Quality Council of Ontario.

Author: Maryam Naji, student LIGS University

Approved by: Amr Sukkar, lecturer LIGS University