Sustainability and Organizational Change: The Role of Organizational Development Practitioners

Sustainability ideas and practices have become the new norms in creating business environments and organizations that are driven by economic incentives, environmental issues, and social issues impacting human development, society, and preserving the health of the planet. Despite the opportunities presented by multiple businesses in response to societal concerns, the corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives, have been criticized as insincere and only geared toward promoting large companies‘ agendas that are not always trusted and believed. The varieties of business review reports and theorized models reflect diverse corporate sustainable agendas and strategies.

In principle, the role of corporations has been accepted as vital contributors that enhance economic progress, and improve the business and social worlds of people and society. Recent perspectives on corporate social responsibility initiatives suggest shortcomings are insincere due to large company agendas that are not always trusted or believed (Illiana et al, 2015). To counteract insincere or questionable approaches, the authors suggest that business companies need to adopt a dialogue perspective of engaging in corporate social responsibility. Jallow (2010) notes that the actions of companies engaged in CSR activities need to reflect ethical considerations. By involving strategic partners such as nonprofit and nongovernmental organizations the above authors suggest that effective CSR is built from conversations and ethical considerations with stakeholders, rather than priorities that protect business economic interests. Thus said, the above arguments suggest that CSR works most effectively when conducted in ethical, credible, and transparent approaches to CSR strategies. Although the concept of sustainability takes so many different meanings, academic and business scholars conceptualize it as business maintenance towards economic, environmental, and social considerations (Crane and Mutten, 2010; Dyllick and Hockerts, 2002). Moreover, the critics of the above concepts have argued that sustainability goals are nothing but priority drives of triple bottom line interests. Correlating the above perspectives (Post et al, 2002) argue against the notion of the business existence as driven solely by profit-making and triple bottom line incentives. To counteract profit-making excessive approaches, the authors propose multiple approaches to business management that balance the economic, legal, and social responsibilities (p.69).

Sustainability challenges, controversies, and prospects will continue to draw focused debates and interests both to theorists, business practitioners, and communities. Drawing from the outlined challenges and existing conversations on the theory and practice of sustainability, this article makes the following contribution. The article starts with a theoretical background influencing corporate sustainability. It then critiques the corporate sustainability models driven by economic gains with the view to conceptualize an alternative model which is conducive to improving community developments in rural contexts. It outlines contextual and collaborative ecological sustainability (CCES) as an alternative approach, followed by a research methodology from an organizational change perspective. The methodological approach suggests that organizational development practitioners play a vital role in knowledge creation through collaborative efforts with stakeholders in designing the CCES model. It is anticipated that such a model will add value to people and sustainable futures in rural communities. Finally, reflections emerging from the adopted model are outlined leading to a conclusion with an emphasis on professional development reflection.

Theoretical Overview Perspectives

This section examines some theoretical literature shaping current corporate sustainability perspectives and models. Corporate sustainability has become a fashion fad for how companies want to be known for how they are prioritizing sustainability agendas. It is not surprising that company reports are populated by sustainable statements purporting to accommodate responsible considerations of their business towards sustainable development. Despite the increasing call, sustainability development tasks of the business goals conceptualized as a balanced approach to managing the economic, environmental, and social issues impacting society remain a complex and continuous challenge. It is not surprising that the espoused and enacted meanings attached to sustainability business draw multiple assumptions. For example (Vanclay, 2004; Prost et al, 2002), take a triple bottom line perspective by considering sustainability as business pursuits of economic results, plus environmental results, plus societal well-being for its stakeholders (p.496). While this perspective argues the end goal of sustainability as stakeholders‘ satisfaction, the main primary focus of economic interests remains the dominating factor of success while environmental and societal issues remain the secondary interests.

Consequently, business actors and practitioners continue to be challenged by the complexities of stakeholders‘ concerns about advancing corporate sustainability goals. Underpinning the stakeholder theory is the assumption associated with solving problems relating to business such as value creation and trade, ethics of capitalism, and managerial mindset (Parmar et al, 2010). From a stakeholder theory perspective, the role of the firm is argued as critical actions centered on managing relationships between firms and stakeholders, accountability of the firm towards societal concerns, and adding value to an identified group of stakeholders (p.435). However, this is not always evident, especially where corporate business entities are excessively driven more by economic financial goals. Despite CSR policies and programs that are embedded in company statutes, the problem of separating ethics from capitalism is cited as a major compromise toward business stakeholders (p.13), consequently, the sound application of stakeholder theory is suggested as the one that puts ethics at the center of the business (p.433). A similar perspective ( Cennamo et al, 2009) argued that stakeholder management can only succeed when ethical business transactions are transparent ( p.501). Additionally, Cochran ( 2007) suggests CSR has evolved and advocates its meaningful alternative approach through the engagement of socially responsible investing, social entrepreneurship, and community investment that strengthen local communities (p.451).

The ongoing discussion and debates about corporate governance and corporate social responsibility about companies acting as corporate citizens have continued to occupy scholars and business practitioners. The prevailing paradigm place shareholders‘ interests as guardians that preserve the long-term future of the business and support the rest of society. It is not surprising that proponents of shareholders‘ powers and ownership contend that shareholders play a significant role in terms of creating environments that enhance sustainable corporate behavior. For example, Crane et al, (2010) contend that shareholding for sustainability contributes to major goals of business ethics such as the triple bottom line of environmental, economic, and social sustainability (p.273). It is not surprising that ongoing theoretical literature perspectives on corporate governance and the role of corporations in society have exposed diverse viewpoints. According to (Pava, 2008) justifications for corporations about CSR goals are viewed as corporations‘ participation in ethical dialogues, and pursuit of educative goals centered on sustainable solutions rather than profit making (p.810). Drawing from the same paradigm lens Dunphy et al, (2002) argue that the sustaining corporation is the one that incorporates human capital as means to support sustainable practices in society.

It cannot be denied that corporations contribute vital services to society and from my perspective much has to be appreciated from their noble contributions to society. Moreover, it has to be also acknowledged that an emphasis on corporations as the sole economic custodians, generators of wealth, and its distribution and sharing with society has its problems. Moreover, it has to be questioned if it is sufficient to view corporations‘ impacts only from the commonly outlined three components of sustainability approaches which includes the economic, social and environmental ( Crane & Marten, 2010; Dyllick and Horkerts, 2002). From my point of view, economic priorities tend to dominate the life operations of corporations. Consequently, these types of behaviors lead to corporations becoming excessively focused on profits gains or priorities, thus putting the social and environmental sustainabilities as secondary priorities. As a result, these discrepancies between corporations‘ espoused and enacted values of corporations‘ business cases raise many questions.

Critical reflections on corporate sustainability models

This first model reflects a corporate sustainable model as critical actions from managers and associated assumptions. According to Epstein (2008), a business‘s corporate sustainability is conceptualized from the management of inputs, processes, outputs, and outcomes used to implement a successful sustainable strategy (p.46). In reviewing the model these observations are noted. The critical role of corporate leadership involvement is used to measure: (1) Input analysis of the external, internal, business, and financial resources; (2) Processes analysis of strategy, structure, systems, programs, and actions; (3) Performance analysis to assess stakeholder reactions and long term corporate financial results. This type of corporate sustainability reflects a model that can only be developed by big companies that have huge financial resources to manage and implement their sustainability programs. Therefore it is feasible to imagine large companies rather than small companies can plan and implement such a sustainable task. More critically it can be argued that such a model puts greater consideration on the financial priorities of its success than the environmental and social impacts. These beliefs explicitly show that the sole purpose of corporate businesses is to generate profit and managers are key drivers of such efforts.

The second model of sustainability draws from organizational change and governance perspectives (Doppelt, 2010). The author argues that improving governance systems and skilled leadership are critical factors that facilitate successful organizational sustainability efforts. The author has identified five key principles of governance towards sustainability (1) To focus on conserving the environment and well-being (2) To continually expand knowledge information and measure progress (3) To engage all affected by the activities of the organization; (4) To distribute equitably the wealth generated by the organization; (5) To provide freedom and support to advance agreed actions (p.253).

The above governance model is similar to the corporate sustainable model, with its heavy reliance on managers‘ active roles to analyze and measure governance systems of sustainability efforts. It must be noted that the success of the governance models as presented above requires multiple levels of organizational change both at cultural and structural systems levels of implementing the best sustainable business practices. While it is true that improving the governance systems will lead to the creation of sustainability goals as an internal intervention assessment, it is also vital that external transformation impacts on stakeholders are considered. This requires more collaborative levels with external stakeholders. Therefore the governance model tends to be internally focused and less demonstrating how sustainability goals are translated into community activism goals of impact.

The third model draws from corporate sustainability (Dyllick and Hockerts 2005) a model that outlines corporate sustainability and its relevance beyond the business case. As described in this model the business case is outlined as a firm‘s efficient use of its natural capital (p.136). The suggested model is described from three types of capital – economic, natural, and social approaches. It is argued that each contributes unique sustainabilities towards the business, natural and societal cases of impact. This model shares perspective similarities with sustainability views as long-term maintenance of systems that sustain environmental, economic, and social considerations (Crane and Matten, 2010). While Crane and Matten support the above triple bottom line three components of sustainability, they also strongly suggest each component needs to be guided by business ethics (p.34). On the contrary, Dyllick and Hockerts view the triple-bottom-line as an incomplete model. They argue that while corporate managers have tendencies toward emphasizing business case criteria, there is also the need to develop clearer indicators of managerial impacts in justifications for corporate sustainabilities in natural and societal cases of impact (p.138).

The fourth model views corporate companies as capable of creating strategic corporate social responsibilities built from their economic incentive goals. Falck and Heblich (2007) outline CSR strategic implications as prescriptive goals that prioritize theoretical management of shareholder and stakeholder approaches. The authors present a strategic planning process in which the CSR planning outcomes are analyzed and evaluated from a decision-making process involving the identification of key stakeholders, emerging stakeholders, and minor stakeholders (p.251). In this model, the success of CSR is attributed to management target priority abilities in assessing monetary returns between key stakeholders and emerging and minor stakeholders. Therefore key stakeholders are given high priority in contrast to emerging and minor stakeholders in connection to structuration and action ways of practicing strategic CSR (p.252). Consequently, CSR strategic practice as viewed from this model focuses on long-term shareholder value as profit maximization. Consequently, the pursuit of a strategy seeking profit is justified and legitimate as long as pursuing social needs is seen as subordinate to profit-making priorities. This model also shares similar perspectives as Cochran (2007), in which CSR is also indicated as enhancing profitability impact n various stakeholders (p.453).

An overview of the literature perspectives on corporate sustainability or sustaining corporations shows varieties of theoretical perspectives and models. First of all common to all the above models is their striking similarities in their view of successful corporate sustainability as promoting long-term profits for the business. Consequently as already stated, critics of corporate sustainability argue that it‘s only centered on economic incentives driven by shareholder demands for their return on investments. Secondly, the models are driven by managers who are placed with demands and pressure to support business strategic goals, sometimes without consideration towards maintaining business ethics. However such approaches have resulted in compromises towards sustainability that support business ethics. Consequently, in this article, I question if corporate sustainability models provide transparent ways of addressing and engaging sustainability challenges of today‘s societal complex issues. As already stated, corporate sustainability has made valuable contributions, but there is a need to develop other models of engaging sustainability approaches besides the ones advocated by big corporate companies.

Contextual and Collaborative Ecological Sustainability (CCES)

The CCES model was designed in response to advancing new directions in organizational development research that encourage focusing on ecological sustainability (Cummings and Worley, 2009). OD interventions that promote ecological sustainability are rare. As noted by Cummings and Worley, (2009), OD practitioners must act in collaboration with stakeholders to create new models and integrated values focused on ecological sustainability (p.709). Additionally, the article by Bradford and Burke, (2004) argues that beyond OD practitioner‘s standard interventions such as individual, group, and organizational interventions, is a need to expand the scope of the field. Although the authors did not specify types of fields, it indeed raised the need for more influence beyond the common focused interventions of OD. Mclean (2006) listed OD interventions as including individual, team, process, global, organization-wide, and community and nationwide. I believe that the role of OD professionals and change agents practitioners within the communities and national contexts is another promising contribution to ecological sustainability efforts. This article contributes toward sustainability knowledge creation as an outcome of the collaboration of multiple agents working to promote sustainability at community levels of impact. For example (Roderick et al, 2011) illustrates sustainability projects conducted through action research approaches that reflect multiple activities and practices of improving social, cultural, and community issues through collaborated leadership actions. The accounts of the projects explore how sustainability projects were developed through contextual connections, dialogues, and diverse agency involvement.

My interest in developing the CCES model was influenced by my experiences as a Director of Neighbours Global Connections (a nonprofit organization) whose mission focused on promoting peacemaking programs and services within rural communities of Zimbabwe. From my perspective, the need to develop peacemaking programs also necessitated collaborating with the community and external actors to work with local communities and community activists to promote ecological sustainability projects. One observed community concern was the need to promote environmental care sustainability through the preservation of species of trees, nature care, and eco-agriculture. Although the nonprofit main activities for several years focused only on peacebuilding the future mission, services and their impact on the community seek to increase community and public awareness of appreciating, understanding, and supporting the rural community’s natural environmental systems. The development of ecological sustainability projects will be conceptualized and created differently in various rural communities. However, its main goals would focus on what I term creating community partnerships (CP), including multiple change agents such as community actors, national and external investors, local business, and government support collaborations. Likewise, as suggested by (Straus, 2002, p.201) for a community to build a collaborative culture involvement of nonprofit, for-profit organizations and local governments need to develop positive experiences collaborating with various stakeholders.

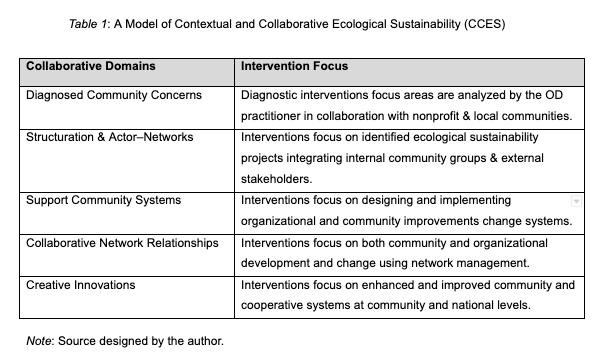

In this article, I have sought to conceptualize such a community model reflecting ecological sustainability in the following intervention approaches. Using a diagnosis and needs analysis, the role of OD practitioners is to identify specific problems and ecological sustainability needs of the particular selected community. Five areas to examine carefully are the diagnosed community concerns; structuration and actor-network systems; support community systems; collaborative leadership interactions; and creative innovations about types of interventions enacted comprising interrelationships between elements in community systems as shown below.

In Table 1 a CCSE cycle illustrates the relationship between the collaborative domain and intervention focus in phases of diagnosing, engaging, and implementing identified interventions towards improving community levels of environmental sustainability projects. The term intervention is used in this article to refer to models and methods that investigate rural community concerns to support identified ecological sustainability issues. Despite the recurring emphasis on community and communities in good corporate governance approaches ( Bessire et al, 2010) there remain discrepancies between theory and practice. The conceptualized CCES model and methodological design discussed below are outlined to fill up the discrepancies.

Methodology

The collaborative inquiry is a critical and integral process of collaborated stakeholder relations at the community and inter-business levels of managing network relations (Straus, 2002). The CCES model depicts the collaborative domain and intervention outcomes of the five interventions (see Table 1). The first part of the intervention involves understanding community diagnosed concerns guided by OD practitioners in collaboration with non-profit leadership and the local community. In the second intervention, the ecologically sustainable projects are identified, analyzed, and acted upon by integrating internal and external change agents’ role engagements. In the third intervention, the focus is on using various methods in designing community support systems such as observation, dialogues, focus groups, community and cooperative meetings, and evaluations toward improving community systems. In the fourth intervention process of managing, networks and quality in network relationships are utilized to strengthen community and business networks. The fifth intervention leading towards sustainability is seen through visible created projects that support human and community sustainability improvements. Collaborative inquiry is a methodology that can be used for managing networks, the quality of relationships in the network, and project interventions outcome (Raelin, 2010). Raelin also underlines the applicability of this methodology in the facilitation of public engagement of a diverse mix of people, issues, and institutions guided by civic participation decision-making principles of (1) design planning and preparation; (2) inclusion and diversity; (3) collaboration and shared purpose and (4) listening and learning. Drawing from knowledge networks and communities of practice theory and practice (Allee, 2000) the OD practitioners contribute strategic support to community development using their OD expertise of intervention skills.

Reflections on the theoretical themes in the CCES Model

To fully comprehend the ecological sustainability in the CCES the opportunities must be understood in terms of collaborative networks created in community contexts. The model is designed to address contextual and collaborative ecological sustainability employed by OD practitioners and focused on improving sustainability communities in rural contexts. The model reflects theory and practice themes emerging from OD interventions that promote ecological sustainability. The CCES model for example suggests that community development strategies and interventions are built to solve social and environmental problems of rural contexts. Driven by incentives to serve and empower poorer or underprivileged communities this kind of CCES sustainability intervention model is not calculated on economic cost outcomes but as opportunities to support underprivileged communities of society.

Issue 1: The rural community systems offer immense opportunities for OD practitioners to further explore and develop sustainable communities

Drawing from model inspirations from Sweden’s Natural Steps (Bradbury and Clair, 1999) new concept models can be developed in rural communities such as planting and preservation of trees as short and long-term stewardship of environmental care. Another concept could focus on designing gardens, and parks in rural contexts drawing conceptualist landscapes that reflect land preservation and environmental art (Cooper, 2014). The role of the OD practitioner in collaboration with local community actors is to diagnose community ecological issues to create sustainability projects and programs conducive to advancing ecological sustainability communities.

Issue 2: The intervention of actor-network and collaborative partnerships.

The role of stakeholder actors and network partnerships is likely to be one useful model for building networked organizations and a learning society (Camarinha et al, 2004; Stiglitz and Greenwald, 2015). Another example of an ecological approach (Blewitt, 2008, pp.173-197) describes the workings of the Ecological Footprint Analysis. For example, the ecological footprint of Greater London is calculated through measurements such as million tonnes of CO2, 49 million tonnes of materials, 6 million tons of waste, 6.9 million tons of food (81% from outside the UK), 64 billion passenger kilometers, 876,000, 000, 000 liters of water (28% of which was leakage). Since the ecological footprint of Londoners is twice the size of the UK, the conclusion is that for Londoners to be sustainable by 2050 an 80% reduction of their ecological footprint will be needed (p.178). From the above examples, it can be seen that collaborated networks and partnerships offer promising potential for creating environmentally sustainable communities.

Issue 3: Building supportive community systems that improve the community well-being of people

Developing supportive community systems that reflect micro dimensions of improvement of environmental, social, and cultural community systems would require the integration of collective and contextual knowledge created within local and national contexts. Bessire et al, (2010) suggest that an enterprise is a community of free and responsible persons. In contrast to profit-driven enterprises, community enterprises are characterized by: (1) humanity care and values that support community development; (2) constituting multiplicity of persons and sub-communities of people working together; (3) interact with other communities, NGOs, and political institutions (p.43). Another model of community support ( Yanus 2010) launched social business projects in Bangladesh that supported local people. Unlike the corporate model of economic sustainability directed by corporate shareholders, the social business model and practice were owned by the poor people and women who participated as equal partners within an organization devoted to helping the poor. In addition to the above model, (Bazonnet, 2009), suggests that multiple actors and engagement is vital for addressing environmental issues that impact various levels of society.

Issue 4: The role of collaborative network relationships and impacts in community projects.

Allee (2000) sums up new assumptions that are driving knowledge networks and communities of practice as (1) building capacity for meaningful conversations; (2) building supporting infrastructure; (3) establishing cultures of learning and sharing; (4) champion new ethics and values (p.13). Allee‘s suggestions offer possibilities through which network relationships are cultivated that renew sustainability efforts at community levels of influence. Of particular interest for this study, the above theories are useful in research on collaborations and organizational change facilitated in community contexts. However, community-level change and engagement are not automatic processes. Therefore considerations towards social network management focus on building trust, knowledge, and consensus rather than hierarchical authority and managing the network as a whole, in recognition of leadership shared network decision bounds, and collaborative decision-making processes (Raelin, 2010, p.138).

Issue 5: Creative innovations centered on cooperative ways of community development

Corporate sustainability theory and practice models integrate day-to-day management decision processes, and operational and capital investment decision-making. As already stated viewing the sustainability impact of company services, products and processes privilege corporate stakeholders. However, my main interest in writing this article has primarily sought to highlight the sustainability approaches that prioritize community involvement and development. Using this approach OD practitioners in collaboration with business entities, non-profit agencies, and community leaders work towards establishing partnerships aimed to conserve and restore community ecosystems (Roberston, 2021). Epstein, (2008) elaborates on this approach in what he defines as corporate philanthropy in which a company contributes to a charity or cause towards societal issues in local communities. The benefits of philanthropy are seen as improving the business environment by integrating social, environmental, and economic goals into alignment (p.98). This author suggests that such creative innovations have unlimited potential to contribute toward collaborative society and human values to benefit rural communities, which reflect the ethical impacts of business in these communities (Jongensen and Boje, 2010). The management of distributive innovations in dynamic ecosystems has also been described as corporations, individuals, and communities‘ collaborations to promote self-governing enterprise ecosystems groups designed to serve communities (Baldwin, 2012). Improving ecosystems of rural communities may result in sustainable development taking many various forms such as land preservations, tree plantations, food preservation, and environmental protection. If doing good is an important value as been advocated in recent sustainability development literature ideas, it must surely be seen to be put into practice within community systems, especially in rural contexts of the developing world.

Conclusion: A Professional Development Reflection

The purpose of the article was twofold. Firstly, it was written to address the research question of the study. Secondly, it was written in response to the call for future directions in OD as a new focus on ecological sustainability. The field of sustainability and organizational change (Dunphy et al, 2003; Jamieson et al, 2016) offers unlimited opportunities for consultants and change agents to diagnose and intervene in multiple projects in community contexts. This article has identified the contributions of corporate sustainability as one model for contributing toward business and societal development. The idea behind reviewing various case models was to explore an alternative approach of sustainability involvement, outlined as contextual and collaborative ecological sustainability and focused on rural communities in developing worlds. The benefits of such an approach were outlined within the model and issues were identified. The author does not claim that this is the only model. However, the conceptualized model demonstrates the need to expand ways of engaging rural communities using theories of knowledge networks, business networks, and collaborative actors networks. The suggested approaches represent an extended and radical rethinking of business and economic models of corporate sustainability. Future corporate social responsibility research and practices need to expand ecological sustainability opportunities presented by challenges in rural village communities. The new models would demonstrate sustainability impacts while improving the lives of community peoples and their environment.

This article contributes to the need for OD diagnostics and interventions beyond the individual-focused techniques, group-focused techniques, and organizational-focused techniques. The new ecological sustainability opportunities would focus attention on collaborative intervention roles of working with multi-dimensional actors of business and community actors. Moreover, it differs from the business focus of sustainability in that it seeks to serve communities with a model less focused on economic returns. This would result in fostering progress at rural community levels of impact as reflected in the CCES model intervention phases that reflect ecological sustainabilities as a product of networking, knowledge learning, and innovative based outcomes. Using the potential of community partnerships and actor networking there are further opportunities to design future research in OD interventions that reflect varieties of community-centered ecological sustainabilities. As suggested from my CCES model, OD practitioners are key players in designing and supporting appropriate community levels of such interventions.

Bibliography:

Allee, V. (2000). Knowledge networks and communities of practice, OD Practitioner,

Baldwin, C. Y. (2012). Organization design for business ecosystems, Journal of Organization Design, 1 (1), 20-23. https://doi.org/10.7146/jod.6334

Bazonnet, C. (2009). Everything environmentally friendly, even theology, SwissLearning Magazine, Winter, pp.42-45.

Bessire, D.,Chatelin, C., & Onnée S. (2010). What is good corporate governance? in Aras, G. & Crowther, D. (Eds), A handbook of corporate governance, and social responsibility, Gower, pp.37-50.

Blewitt, J. (2008), Understanding sustainable development, Earthscan.

Bradbury, H. & Clair, J. (1999). Promoting sustainable organizations with Sweden Natural Step, Academy of Management Executive, 13, 63-74

Bradford, D.L. and Burke, W.W. (2004). Is OD in crisis? Journal of Applied Behaviour Science, 40 (4), 369-373. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886304270821

Camarinha – Matos, L.M. & Afsarmanesh, H. (Eds).(2004). Collaborative networked organizations: A research agenda for emerging business models. Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Cennamo, C.Berrone, P. & Gomez-Mejia, L.R. (2009). Does stakeholder management have a dark side? Journal of Business Ethics, 89 (4), 491-507.

Cochran, P.L.(2007). The evolution of corporate social responsibility, Business Horizons, 50, 449-454.

Cooper, P. (2014). Conceptualist landscape. Parkland Publishing Limited.

Crane, A. & Matten, D. ( 2010). Business ethics. 3rd ed. Oxford.

Cummings, T.G.,& Worley, C. (2009). Organizational development and change. 9th ed. South-Western Cengage Learning.

Doppelt, B. (2010). Leading change toward sustainability, 2nd ed. Greenleaf Publishing.

Dunphy, D., Griffiths, A., and Benn, S. (2003). Organizational change for corporate sustainability, Routledge Taylor and Francis Group.

Dyllick, T. and Hockerts, K. (2002). Beyond the business for corporate sustainability, Business Strategy

and the environment, 11, 130-141. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.323

Epstein, M.J. (2008). Making sustainability work. Best practices in managing and measuring corporate social, environmental, and economic impacts. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Falck, O, & Heblish, S. (2007). Corporate social responsibility: Doing well by doing good, Business Horizons, 50, 247-254. available online: www.sciencedirect.com

Illia, L.Romenti, S., Zyglidopoulos, S. (2015, Fall). Creating an effective dialogue about corporate social responsibility. MIT Sloan, 57 (1), 20-22.

Jallow, K. (2010). Education for ethics and socially responsible behavior, in Aras, G. and Crowther, D. (Eds), A handbook of corporate governance and social responsibility, Gower, pp.381-394.

Jamieson, D.W.,Barnett, R.C., & Buono, A.F.(Eds) (2016). Consultation for organizational change revisited. Information Age Publishing Inc.

Jorgensen, K.M. and Boje, D.M. (2010). Resituating narrative and story in business ethics, Business Ethics, A European Review, 19 (3), 253-264.

Lindorff, M. (2007). The ethical impact of business and organizational research: the forgotten methodological issue? The Electronic of Business Research Methods, 5 (1), 21-28. available online: www.ejbrm.com

Massarick, F. & Pei-Carpenter, M. (2002). Organization development and consulting. Jossey-Bass Pfeiffer.

McClean, G.N. (2006). Organizational development. Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Parmar, B., Freeman, R.E., Harrison, J.S., Wicks, A.C., Purnell, L., De Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The State of the art, The Academy of Management Annals, 4 (1), 403 – 445.

Pava, M.L.(2008). Why corporations should not abandon social responsibility, Journal of Business Ethics, 83, 805-812.

Porter, M.E.& Kramer, M.R. (2006). Strategy and Society: The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility, Harvard Business Review, 84 (12), 78-92.

Post, J.E., Lawrence, A.T. & Weber, J. (2002). Business and Society: Corporate, 10th ed. McGraw-Hill.

Raelin, J.A. (2010). The leaderful field book: Strategies and activities for developing leadership in everyone. Davies-Black.

Robertson, M. (2021). Sustainability: Principles and Practices, 3rd ed. Routledge.

Roderick, I., Kleinaite, I., Downey, P. (2011). Working through community and society, in Marshall, J., Coleman, G., and Reason, P. (Eds), Leadership for sustainability: An action research approach, Greenleaf Publishing, pp.190-204.

Stiglitz, J.E. & Greenwald, B.C. (2015). Creating a learning society. Columbia University Press.

Vanclay, F.(2004). The triple bottom line and impact assessment: How do TBL, EIA, SEA, and EMS relate to each other? Journal of Environmental Assessment and Management, 6 (3), 265 -288.

Yanus, M.(2010). Building social business, Public Affairs Books.

Author: Sydney Moyo, student LIGS University

Approved by: Amr Sukkar, lecturer LIGS University