Organizational Consulting: A Theoretical and Practical Perspectives to Management Consultancy and Research

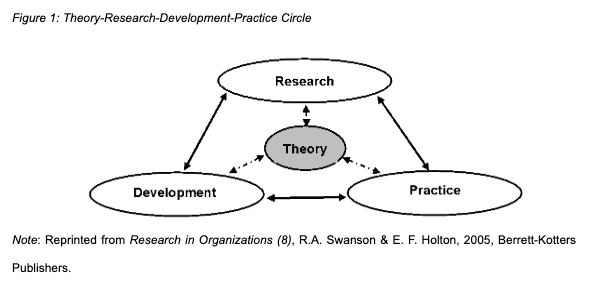

This chapter is organized in three sections. The first section focuses on the foundations of organizational consultancy and consultant’s role tasks. The second section provides an overview of research approaches in in management consulting, including theoretical foundations shaping these perspectives. The third section discuss some theoretical and practical intervention approaches in management consulting and implications for developing consulting practices. Throughout the study I attempt to highlight some of the contextual and collaborative themes emerging from discussing organizational consulting using the model of theory, research, development, and practice (see Figure 1, p.4).

There are varieties of definitions associated with management consultancy. Newton (2010) defines consultancy as engaging dialogue in cliental organizations to apply expertise resulting towards developing recommendations, considering the specific needs and context of that organization (p.5). Consultants employ several methods or approaches which adds value in evaluating ideas and recommending organizational change. One critical task for organizational or management consultants is to make more explicit the theoretical and practical learning intervention and knowledge creation processes influencing their practice.

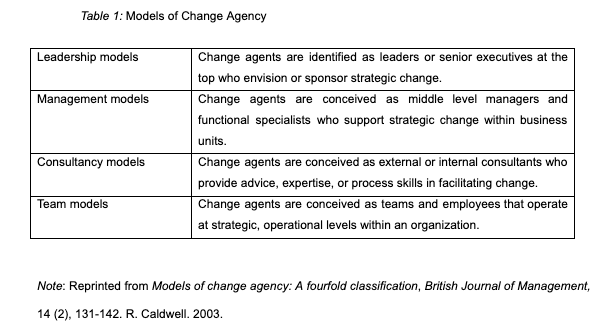

The study was conducted as a motivation to understand the knowledge creation models influencing the practitioners of organizational consulting practice, including understanding my researcher role identity shaping my consulting practice. Crowther and Lancaster (2009) argue that this can be accomplished by developing complimentary consultancy and research skills applied in cliental work such as management consultancy skills, management research skills and self-development skills. As suggested by organizational consultant practitioners (Czerniawska, 2002; Burno and Jamieson, 2010) the role of external consultants allows engagement for a specific consulting project where the change agent act as an independent practitioner that contribute expert knowledge and experience that is not present in the organization. Whereas internal consultants are defined as full members of the organization who has a role as a consultant to the business either drawing from human resources or internal change management specialists (Hodges, 2017; Newton, 2010). Drawing from Caldwell (2003) four models of change agency apply different roles in supporting management of change cited as roles of leadership, management, consultancy, and team roles (see Table 1). The specific views of four change agency models and practical relevance towards management of change are contrasted.

This paper extends from the change agency of consultancy models and develops new ideas on organizational consulting and development by reviewing the extant literature to identify dynamics of knowledge creation using a mix of contextual and collaborative approaches of working within cliental organizational systems. The view I take is that effective organizational consulting management and intervention is developed from understanding management consultancy and facailitation of change using the interactivity and integration of theory, research, development, and practice cycles (Swanson and Holton, 2005) as illustrated below. Thus, as a practitioner-researcher it is useful to examine how the theoretical and practical implications of external change agent consultants collaborate with internal management change agencies in facilitating and implementation of change. Throughout this study, I refer to practitioners who do research as practitioner-researchers. Gummesson (2000) outlines the role of management action scientists as developing an understanding of the specific decision, implementation, identifying change process in cases with which they are involved and generating a specific theory never finalized but continually transcended (p.208).

Swanson and Holton, (2005, p.8) suggested that the four domains of the theory-research-development-practice can be used as a starting point for knowledge generation. Drawing the above cycle, the research question of this study sought to find out: How consultants construct meaning and intervention approaches in organizational consulting? The sub questions are outlined below.

- Question 1: How is research in consulting undertaken to expand professional knowledge base and leading to development and improvement of practice?

- Question 2: How is organizational consulting practice explored as research that has resulted in innovative models of organizational change and towards improvements in the profession?

- Question 3: Which theory is applied in consulting to enable a better understanding of consultant-client phenomena in management consultancy and research?

- Question 4: How is consulting development illustrated as changes established leading to new organizational models and methods applied?

Approaches of Research in Management Consulting

The disciplinary study of management consulting links its roots to the practice of management research approaches. Drawing from various management research approaches (Bell and Thorpe, 2013; Stokes, 2011) management researchers can be located to the primary focus or objective of their research. Critical to their researcher commitments are choices of theory and methods guiding their research (Bell and Thorpe, 2013). In this section I focus on the theoretical imparts in management research and consulting. I shall discuss the methods impacts in the next section. Although there are different choices that management theorists and practitioners ascribe towards, the literature in managing consulting focuses on three types of management research priorities: management researchers as either; (1) theory testing with emphasis on testing theories and processes of measurements; (2) theory building with focus on developing theories based on observation, experience and intuition; (3) problem centered / practical research, aimed at investigating a practical problem in a specific organization or management context (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). Rather than focusing on theory testing research, this study focusses towards exploring management as practice drawn primarily from problem centered and theory building commitments. Essentially organizations use consultants to help improve business related problems, however the theoretical skills, experiences and values consultants bring to their work is also key to the success of client-centered consultancy.

As expected, management practice integrates varieties of perspectives (Drucker, 2006; Magretta,2002; Mintzberg, 2009). According to Drucker management practice is not about imposing universal standards of rationality to all business entities, but responsibility to shape the economic environment through planning, initiating and implementation of changes in that economic environment (Drucker, 2006, p.11). According to Mintzberg management practice is conceptualized through managing as art, craft, science integration. The craft contributing experience of practical learning, while science contributes the science of systematic analysis and art the ability to create vision insights (Mintzberg, 2009, p.11). A similar approach (Magretta, 2006) defines management practice as creating management business that enhance value creation, business models, competitive strategy, and organizational design. Drawing from my OCD experiences of practices, I view management consulting as providing opportunities of working with cliental organizations to contribute practical and useful knowledge that facilitates organizational change management drawn from organizational change and development intervention that improves business and organizational effectiveness (Cummings and Worley, 2009; Jones, 2013; Haynes, 2002). Building from the above knowledge perspectives the nature of management consulting can be practiced from management model roles or consultancy model roles (Caldwell, 2003; Mintzberg, 2009; Newton, 2010; Wickham, 2004). A traditional approach of management consultancy role is defined from general manager roles associated with skills of planning, organizing, staffing, directing, and controlling. Moreover, a critique of this classical approach of management has suggested a productive approach where managing is examined from roles managers perform rather than functions they undertake. Mintzberg proposes ten roles of figured, leader, liaison, monitor, disseminator, spokesperson, entrepreneur, disturbance handler, resource allocator and navigator classified under interpersonal roles, information roles and decision roles (Mintzberg, 2009, p.45). Decisions to use a consultant is driven from consultants perceived value they add to the business such as provision of information, specialist expertise, a new and innovative perspective, support for internal arguments, gaining critical resource and facilitating organizational change (Wickman, 2004).

Whilst consulting projects involve a combination of above elements, specialties of consultants are guided from experience, education, and training. Consultants approaches either from internal or external interventions provide strategies of development and change that offer problem solving and improvements towards cliental concerns. More it is important that the consultant communicate the value they add to the cliental needs. For example, the research on consulting as a strategy for knowledge transfer (Jacobson et al, 2005) demonstrated the role of consultant researcher knowledge transferred to key decision makers and health systems research consulting units which were examined within three consulting case projects. As illustrated from the knowledge transfer-focused consulting, the consulting focus describes clients consult process where consultant knowledge, expertise and skills are sought to develop policy and practice recommendations that are grounded in context-specific applied research and driven from theory of consulting initiatives and learning interventions (Jacobson et al, 2005, p.4, London & Diamante, 2018). A similar perspective locates the relevance of contextual approach from problem-based research (Tracy, 2007) as offering problem-based analysis processes that are draw qualitative analysis that are interesting, practically important, and theoretical significant. Although from Tracy perspective context takes a central role in research and a priory theory a secondary role, the focus of my research examine research within my management consulting practice as shaped from a multiple interactivity within the dynamics of integration of research, theory, practice, and development (Swanson & Holton, 2005).

It is important to underscore that managing consulting embodies consultants and organizational managers challenges and opportunities of collaborating to work through real life management problems within organizations. As already stated, the goal is to apply consultant advice and expertise to support cliental business outcomes that create value for development and effectiveness. This role entails consulting, not manage or to lead. From this approach consulting is broadly defined as a process of transferring expertise and process knowledge from the role contributed by the (consultant) to another (the client) with the aim of providing advice or solving problems (Block, 2011). Change agency roles of management and leadership roles differ from the consultancy roles. Consultancy change roles emphasize the dynamics of interaction between consultant and client. On the contrary leadership roles use top-down approach to implement needed changes. According to Newton, the consultancy context can be understood by considering how consulting management fits with the operations of the client enterprise with an emphasis on three client-centric core processes a consultant needs to consider as; (1) the consulting engagement process to reflect the consultant work to deliver; (2) the client change process to demonstrate the change agenda in the business; (3) the client operational process to reflect how the consultant work ( Newton, 2010, p.58).

Approaching management consultancy-based research from the client-centric intervention approach the consultant identifies knowledge and skills to address either individual, group or organizational issues of concern and creates methods that will lead towards selected developmental needs (Viljoen, 2015; Lowman, 2016). However, building from the intervention approach, the role of organizational change agents is to design interventions that support organizational changes. Additionally, the role of the practitioner-researcher in management consultancy research requires the need to reflect contextual or dialogical issues that arise during the intervention processes supporting organizational change. Crowther and Lancaster (2009) outlined main researcher problematic dilemmas in the process of consultancy-based management research as ethical problems issues; access issues; cultural issues; client-consultant issues; conflicting stakeholder issues and resource and budget issues (p.36). Therefore, approaching research in management consultancy explored from the theory-research-development-practice cycle (Swanson & Holton, 2005) encompasses both the theoretical and applied research which provides a richer reflection on the domains of the cycle while also advancing research in organizational consulting. The study conducted on organizational change research and practice (Armenakis and Harris, 2009) reflected organizational practitioners’ journey within the six indicators or themes impacting change management namely, (a) five key change beliefs; (b) emphasis on change recipient involvement and participation; (c) effective organizational diagnosis; (d) creating readiness for change; (e) managerial influence strategies.

The relevance of the above themes is important in that they contribute richer understanding of research consultant -client dynamics in management consulting, and I shall refer to their significant relevance to my study in the next section. For now, I shall focus on the five key change beliefs that are suggested as providing the basis of change recipient motives, to support change efforts and successful organizational change. The five key beliefs are summed as; (a) discrepancy refers to the belief that change is needed and measures current state of the organization and its future; (b) appropriateness reflects the belief that there is need to design a specific change to address a discrepancy to adjust the situation; (c) efficacy refers to the belief that the change recipient and the organization can successfully implement a change; (d) principal support refers to the belief that formal leaders in an organization are committed to the success of change; (e) valence reflects the belief that change is beneficial to the change recipients (Armenakis and Harris, 2009, p.129). The importance of the above key beliefs reflects the theoretical and practical underpinnings of knowledge creation which organizational consulting practitioners could also employ. The authors approach towards management consulting resonates with Newton consultant client processes and purposes. Additionally, it resonates with problems and issues experienced in management type research (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). As highlighted in the research and review approaches, the primary objective of consulting practitioner is to be able to contribute knowledge practice, learning and improvement towards enhancing the company own ability to change. Consultants are brought in to provide advice and knowledge insights into current change situations designed to improve new and innovative perspectives (Wickham, 2004; Jacobson et al, 2005).

Approaches of Intervention Approaches in Management Consulting

In this section I explain the intervention approaches consultants develop in varieties of case practices. The four models of consulting practice intervention are discussed before the final model is conceptualized reflecting the intervention method that I use in my organizational consulting practice. According to Newton (2010) consultants do not use the management consultant title but use familiar titles such as business advisor, strategy consultant, operational consultant, market consultant or leadership consultant. Moreover (Wickham, p.33) argues that the importance of management consultants is the value they bring to the client organization by providing advice and recommendations to managers based on set of skills, specialist expertise, experience and values guiding their work. Although intervention is not a simple matter it is my position that interventions consider contexts in which they exist in consideration of political, social, and environmental impacts. Therefore, the choice of interventions selected require consultant and client collaborative understanding in consideration of multiple scenarios of intervention processes.

Model One: Consulting Intervention as Dialogic Perspective

The first model feature, MacIntosh et al, (2012) study of practice and knowing is examined as a dialogic intervention perspective emerging through dialogue between management consultants and organizational managers. The authors suggest the importance bridge building of dialogue as an outcome of negotiating different understanding of interests and emerging story telling between the dialogic encounters. As suggested examples of the role of dialogic perspective in knowing and practice captures rich dialogues between academic and policy maker, collaboration between researchers, and reflexive changes in career managers of elite and non-elite backgrounds, researcher-practitioner and practicing research. Drawing from the above example the theory building guides the research processes, while improving management practice within interactivity of organizational researchers and managers coordinated ways of knowing from diverse positions.

Model Two: Consulting Intervention as Consultant-Client Interface

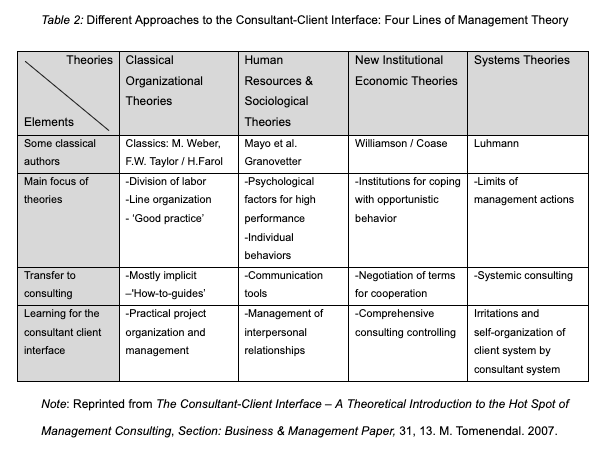

The second model examine consultant-client interface (CCI) in Hot Sport Management Consulting (Tomenendal, 2007) and suggests that challenges or frictions can be minimized by finding common ground for the different systems. The author provided an analysis of CCI from a comparison of four perspectives: (1) Classical organizational theories which focus on hard factors in managing organizations; (2) Human resource oriented and sociological theories which focus on soft factors in management; (3) New Institutional economic theories which examine interactions between consultants and clients; (4) Systems theories which create general knowledge within and between systems (Tomenendal, 2007, p.4).

As indicated above describing and explaining consulting illustrates adopted processes on the consulting interface as distinct elements in the emerging theory of CCI. Linking this study from the theory-research-development-practice cycle, an analysis of integrated theory of CCI demonstrates multiple approaches of knowledge created from identified theoretical paradigms. The link from research to practice is seen as theoretical improvements of consulting practices that are developed within organizational and management systems influencing business environmental contexts. Additionally, the model confirms the importance of client-centric consulting three core processes as suggested in management consulting (Newton, 2010).

Model Three: Consulting Intervention as Gestalt Organizational Development

The third model explores organizational consulting practice from an analysis of intervention methods of organizational consulting from comparisons of theoretical perspectives of classical organizational consulting, modern organizational consulting, and postmodern view for organizational development consulting (Saner, 1999). Saner describes and elaborates the foundations; (1) classically organizational consulting influenced from the foundations of functional and traditional methods centered from Taylorism which primarily focused towards increasing productivity through improvement of structures; (2) modern organizational consulting is associated with human relations approaches such as group dynamics, sensitivity training and motivation theories and associated roles collaborator in problem solving, trainer and educator; (3) postmodern organizational consulting approaches argue that the role of consultant has become more complex and suggest the need to acquire new competencies to be more responsive towards client organization’s multiple needs (Saner, 1999, p.12).

Drawing from gestalt therapy approach (Saner, 1999) has argued that the usefulness of this approach as the gestalt oriented practitioner or gestalt oriented organizational development consultants motivation in working with clients emphasize creating awareness and client task require organizing amounts of information awareness and with intervention needs shifting from minimizing chaos and confusion by helping client remain in a state of tension and not closure while working on improving organizational issues (p.17). According to Saner, the roles of gestalt-oriented organization development consultants entail two key aspects: (1) role of supporting clients to live with tension and uncertainty, helping clients making choices towards individually and collective development; (2) role of experiment coach helping clients to focus on less energy in finding right solutions but rather explore imaginative and developmental experiments (Saner, p.18). Linking implications of gestalt oriented organizational development theory, it is important to note that the theory-research-practice-development cycles research stimulate conscience of awareness. Theory building and practice in gestalt organizational consulting emerges as creative intervention that support cliental awareness about themselves and their surrounding world.

Model Four: Consultation Intervention from a Complexity Perspective

The fourth model discusses the practice of organizational consulting from the theory of complex adaptive systems (Shaw, 1997). Shaw examined the impact of consulting from a radically different conceptualization how organizations change. Shaw adopts a complex science intervention approach in which dynamics processes of interactivity and connectivity emerges as networks of adaptive agents free from a central control system (Shaw, p.235). Dooley (1997) has argued that the complex adaptive systems provide an inquiry towards understanding systems by looking for patterns within their complexity that describe evolutions of the system. Drawing from the complexity perspective (Shaw, 1997), suggests the consultant role of change agent who; (1) studies self-organization systems, with its environment; (2) understands change as unfolding in ongoing tensions of stability and instability, and change as an unfolding activity; (3) intervenes in the conversational life in organizations in which people co-evolve action contexts; (4) Invites exploration of the relationship between system formal agenda (what the systems knows) and multitude of informal narratives (what the shadow systems knows) to develop feedback loops; (5) amplifies sources of difference, friction, and contention so that complex learning might occur (p.241).

Consulting from a complex perspective differs from a planned change where consulting stages are achieved through stages or phases of the consulting cycle (Schein, 1988; Block, 2011). The paradigm of consulting from planned change interventions adopted from classical approaches has provided historical background understanding of the field. Holbeche (2006) argues change agents need to move from trying to change organizations only from diagnostic interventions but instead look at how they might help them ready for change to move to a state of self-organized criticality. The focus of change interventions moves from planning change towards facilitating change as knowledge situated in contexts.

Model Five: Consultation Intervention as Contextual and Collaborative Analysis

The fifth model is to offer an illustration of an organizational consulting practice using what I have called a contextual and collaborative model (CCM) of intervention approach in organizational change which is grounded in both theory and practice. The CCM method was developed during my doctoral research while investigating the case study of organizational change and development using contextualizing and collaborative change approaches in organizational practice contexts. My interest in the contextual and collaborative perspective was because my experiences as external organizational consulting practitioner enabled me to encounter the complexities of facilitating change. Drawing organizational behavior management (Martin and Fellez, 2010; Gordon, 1999) my intervention skills used diagnostic approaches of implementing organizational consulting from behavioral science perspective. Moreover, the complexities of external and internal environments, including consulting across different management practices and cultural diversities within organizations made me quickly realize that using the diagnostic techniques alone was not sufficient for facilitating change successfully. I had experienced levels of success and challenges in working with various clients. From my perspective a combination of contextual awareness, collaborative potential and relational leadership skills of the change facilitator were key issues in successful interventions in my organizational consulting experiences. Additionally, one key critical issue is acknowledging that multiple perspectives impact knowledge production, management researchers in consultancy experience problems and issues in conducting research (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009). It is important to understand the prevailing circumstances and unfolding learning experiences emerging from consulting practices.

Reflecting My Organizational Consulting Practice

The contextual and collaborative model (CCM) centers consultant collaborative roles with clients constructed from multiple approaches as illustrated below. The purpose of CCM is to advance research in organizational consulting that incorporates the outlined considerations.

- Researcher theoretical understanding. The CCM consulting draws from organizational change and development (OCD theory) as a planned and relational intervention. Drawing from diagnostic and dialogic theories (Bushe and Marshak, 2009; Marshak and Grant, 2008), CCM approach to consulting suggests creation of knowledge and intervention in organizational change as an outcome of understanding contextual issues and organizational relationships. Although the above authors lean more towards new dialogical approaches, the CCM model integrate both the diagnostic and dialogical interventions.

- Contextual understanding. The focus of CCM consulting is to identify external of internal factors hindering or facilitating change or learning interventions. Contextual reflections are also examined within the phenomenology meanings and experiencing of consultant-client relating. Phenomenology is the study of people’s conscious experience of their lifeworld (Van Manen, 2014; Moustakas, 1994). Using phenomenology, the study also revealed contextual and multiple perspectives and understanding meanings of consultant-client experiences.

- Collaborative understanding. An important element in the CCM consulting dynamics is collaborating with managers. Collaboration is considered to reach understanding towards joining his or her specialized knowledge with manager’s knowledge of the organization.

- Organizational analytics understanding. Another vital element in CCM consulting is understanding the processes of engagement which reflect the need to analyze both diagnostic and dialogical engagement with clients. In CCM consulting I have identified seven analytics and their contributing potentials such as: (1) Consultant role – clarifies awareness and engagement role of the consultant; (2) Constructionist role – ability to create organizational knowledge creation to ensure clarity of business problem and the problem-solving processes; (3) Contextual role – ability to identify, analyze and interpret both external and internal factors impacting cliental situations; (4) Collaborative role – working jointly with clients throughout the agreed engagement where the client provides knowledge of the business and issues and consultant provides knowledge of techniques and skills to help solve the problem; (5) Content role – engage conversations and dialogue with clients to clarify expectations, issues to be addressed, concerns and risks; (6) Consensus roles – establish agreements with clients to agree what different roles they will each perform, leading to clarified responsibility and accountability; (7) Collaborative action roles – while consultants transfer expertise skills and knowledge to the clients, the role of managers is to implement action plans that will make the system more effective.

- Intervention understanding in CCM. The key issue for an interventionist is to know how to help the client through an intervention system. Using the CCM model the effective intervention comprise an analysis of core activity of any system which leads to (1) to achieve its objectives (2) to understand its internal environment and (3) to adopt to and diagnose the relevant external environment; (4) to make explicit the proposed solution processes in collaboration with organizational managers and leaders. It is important to note OCD interventions generally incorporates various interventions targeting either individual levels, group or team levels and organizational levels. London and Diamante (2018) suggest that intervention for consultants are based on the following five step process for learning intervention (1) Needs analysis to discuss client view of any desired intervention; (2) Contracting to propose learning solutions, expected learning outcomes, resource requirements and costs; (3) Develop learning design and development model to match organizational needs; (4) implementation by testing the program and revising as necessary; (5) Evaluating to assess effectiveness and return on investment.

- A Scientific practitioner understanding. The key emphasis of CCM model insists on practice-based approach to solve or improve organizational cliental issues of concern, where knowledge created is translated towards solving problems at hand and combined with wisdom for actions to be considered, emerging from consultant-client interactions. According to Lowman (2012, p.153) the science of organizational psychology is to make research relevant to practice leading to assessing variables that are central to organizational life. Drawing from this perspective organizational consultants or practitioners contribute towards the knowledge creation of science and research towards creating science and research that are practice relevant (Lowman, 2012, p.155).

Methodology

Because I approached this study from an organizational consultant intervention, I chose the contextual and collaborative model (CCM). The use of CCM approach serves as both an intervention and reflexive model in understanding organizational consulting practice. The contextual and collaborative model (CCM), a multiple approach reflects both my practitioner- researcher processes, encompasses core relations constructed and contexts awareness. The aim of CCM is suggested as an approach to help organizational practitioners and researchers investigate and account their consulting-client ways of knowledge building. Drawing from a social constructionist understanding of theory building (Gergen & Thatchenkery, 2004), social-constructionist research is concerned with seeking explanations how social experience is created and given mean, with emphasis on the specific, local, and particulars of lived experience of those studied. Using the CCM approach, I identified and analyzed consulting practice research that engages in what I call intervention inquiry. Drawing from organizational consulting psychology perspective (London and Diamante, 2018) suggests that learning intervention consultants account the reflexive lessons learnt through designing interventions to support organizational change. As already outlined in the previous sections, the study is examined from the theory-research-development-practice cycle to expand professional knowledge and improvement of organizational consulting practice. Reflecting on above approaches allows multiple ways of conducting organizational consulting explored in consultant-client relations created within contexts and collaborative interactivity. The context refers to multiple domains within which consultative activities occur and types of consulting in business or organizational domains. Collaborative refers to how a consultant interventionist works within the client systems to help the client achieve three core activities of any system cited as: (1) to help generate valid and useful information; (2) to help create conditions in which clients can make informed and free choice; (3) to help clients develop an internal commitment to their choice (Argyris, 1971, p.31).

Primarily in CCM consulting I draw from qualitative research designs approaches to provide understanding of organizational consulting change, learning and development outcomes. (Creswell, 2013) outlined qualitative research as assumptions and use of interpretative and theoretical frameworks that inform the study of research problems to elucidate a deeper meaning of individuals or groups in natural settings. Therefore, the use of qualitative research design in CCM consulting enables me to be reflexive of my consulting experiences while seeking to provide holistic accounts within a complex picture of issues under study. Moreover, the use of both quantitative and qualitative research designs can be used in consultative problem-solving processes based on researcher epistemological and ontological orientations either of deductive or inductive researcher. Crowther and Lancaster (2009) suggest the process of deductive research approach as generation of theories and hypotheses using rigorous tests. Whereas inductive research approach draws practitioner own experiences and other people in work organizations to describe or observe leading toward explanation of a problem or issue to be studied. Similarly, Swanson and Holton (2005) outlines differences philosophical views of positivism and interpretivism. The positivism focus on quantitative methods is used to test and verify hypotheses towards related studies. On the contrary interpretivism research is concerned with understanding subjective meanings on how individuals or members understand and make sense of their natural contexts (Swanson and Holton, 2005, p.19). Drawing from my consultant researcher roles in this study, the inductive approach to conducting management research in the use and qualitative investigations was more conducive than the deductive approach. Towards this goal, the study sought to understand how the production of knowledge emerges in organizational consulting using the theory, research, development, practice cycles as an intervention methodology and as a contribution in my research-practitioner approach as a practitioner in organizational consulting. Additionally drawing from the phenomenological methodology (Creswell, 2013, p.104), to understand experiences of organizational consultants, and to describe the essence of the experience as contributing knowledge creation toward organizational consulting research practice and development.

Findings

Organizational consulting as an intervention activity requires theories, practice contexts and selection points of intervention conducted within the sponsoring system. The organizational analysis of the four models is presented within the perspective of theory-research-development-practice cycle (Swanson and Holton, 2005) to demonstrate organizational consulting knowledge emerging from five compared multiple models. Three primary goals guided my findings. Firstly, my goal was to provide an integrated approach of theory and practice processes and outcomes in consulting management research to enable readers and practitioners to appreciate, connect and understand the description of the consulting contextual and collaborative practices. Secondly it was to provide understanding of the types of consulting intervention enacted. This is consistent with an intervention model (Argyris, 1971, p.15) who outlines intervention as consultants entering ‘into an ongoing system of relationships to come between or among persons, groups, or objects for the purpose of helping. Cockman et al, (1992) also differentiate between four distinct interventions styles employed by the consultant namely: acceptant style, catalytic style, confrontational style, and prescriptive style (pp.22-24). Correlating approaches of management consultancy also suggests variations of consultancy as directive consultancy; non-directive consultancy; process-oriented consultancy; and task-oriented consultancy (Crowther and Lancaster, 2009, p.57). Thirdly, using the phenomenological analysis my goal was to shed insights in consultant-clients participative experiences using the phenomenon called the imaginative variation or structural description (Creswell, 2013, p.82).

Emerging from the descriptions is organizational consulting knowledge creation providing multiple opportunities towards fundamental understanding of contextual and collaborative linkages of consultants-cliental interactive dimensions. A related point is also outlined by Miles and Huberman (2020, p.5) that qualitative research focuses on naturally occurring events and so that we have a strong handle on what ‘real life’ is like. The above qualitative multiple lenses are applied as organizational analysis and actions that guide experiences and knowledge creation and facilitated change in organizational consulting as reflected on five case models to highlight common and unique features of organizational consulting contexts. The process of organizational consulting reflects the impacts of theory-research-development-practice demonstrated in the four models of organizational consulting practice. Each model practice is summarized in the next turn.

The model one consulting intervention in practicing and knowing management (MacIntosh et al, 2012) sought to foster understanding of relationships and interactions between theory and practice to explore practicing and knowing as dialogic and co-constitutive processes. Drawing from this perspective management practice and development is interpreted as research knowledge created within relational contexts of interaction which leads to improvements in the practice. The collaborative research practice depicts diverse roles between researchers and executives acting or policy makers creating management ways of knowing and practice. Their different agendas and stories reveal the political dynamics of research, which demonstrates collaboration as a transactional process of appreciating their unique professional contexts. The strength of practicing and knowing management is suggested as built from a dialogic theoretical perspective. The development of practice and knowing emerges from the lived experiences of dialogues that exposes willingness and motivation to learn from the collaborative knowledge exchange of researchers and executive managers. The imagination variation of their phenomenological exposure involves viewing the diverse experiences of researchers and policy makers from their different angles of acting and learning. MacIntosh et al, 2012) concluded the following:

Rather than working with labels ‘researcher and practitioner’ from a dialogical perspective suggests that the actors are all practitioners who bring different modes and expertise of practicing to the dialogue (p.3).

Therefore, by adopting the above intervention approach, the consequence is that the above model example positioned consultant-clients as joint problem solvers. The choice to adopt a non-directive consultancy enabled consultants and managers to dialogue, raise questions that led to joint proposed solutions.

The model two consulting intervention in consultant-client interface (Tomenendal, 2007) sought to understand interactions of clients and consultants as knowledge created from different management theories used to support consultant-client interface. Contrary to model one approach which suggests ways of consultancy management research practice as relational developed, model two type of consulting research focus on theory building as a function of research development by explicating the management theories and their contributing potentials to support descriptions of consultant-client interface. The strength of four lines of management theory (see Table 2) creates and transfer specific knowledge to consulting as hard facts, soft facts, negotiation of terms for cooperation, and systems development. The consultant-client interface from this model suggests that theories are needed for understanding consultant-client ways of relating to improve projected anticipated learning outcomes. From my perspective consultants and clients are guided from associated management theory perspective. Therefore, the role of the consultant is to use selected management theory as an intervention, but only guided by cliental opportunities or constraints to demonstrate competent use of theory to address practical and relevant outcomes of identified problem issues. Since the above consultancy intervention approach depicts consultants as experts drawn from their theoretical orientations, a directive consultancy is adopted which is based on consultant proposing specific guidelines or directions as projected outcomes within the consultancy-client interfaces. Moreover, from a phenomenological structural description, the contexts of both consultant and cliental systems need to be understood from both theory and practice orientations. Additionally, it requires the consultant to clearly specify the type of consulting knowledge transferred emanating from line of theory adopted in an intervention.

The model three consulting intervention as Gestalt oriented organization development (Saner, 1999) suggests that the work of the consulting practitioner is that of bringing awareness training to in terms of helping the client develop broader and deeper awareness of what is going on, needed and actions to be taken (p.6). The author’s starting point reflects the development-practice-theory cycle of creating knowledge in the consulting world through the analysis of postmodern theatre, compares organizational theories of classical organizational consulting, modern organization consulting and postmodern consultants. A discussion of organizational consulting field is compared to the theatre field in the mid-1960s, expanded towards modern and to postmodern theatre (p.15). According to Saner (1999) evolution of organizational development consulting is identified as: (1) Classical organization consulting postulating traditional and functional experts who prescribe selected intervention methods through improvement of structures; (2) Modern organization consulting postulating human relations where organizational consultants focus on human process, group dynamics, sensitivity training; (3) Postmodern Gestalt - oriented organizational development consulting where the consultant move beyond prescriptive and right approach methods of intervention aiming to minimize chaos and confusion to help the client in a state of tension and not to seek closure, but support, experiment and creative artist roles (p.18). As suggested by Tolbert (2004), contributions of Gestalt therapy require organization & systems development (OSD) consultant to immense in the organism and environment interaction within cliental systems in order to: (1) attend, observe shared observations with clients; (2) attend one’s own experience thus creating presence; (3) focus on the energy in the client system; (4) stir clients interest to support mobilization of energy into actions; (5) facilitate meaningful contact between members of the client system; (6) help clients to progress through cycles of experiences; (7) support processes of completion of units of work ( p.10).

From an organizational development cycle efforts consultants address the demands and complexities of practice through a multiple perspective of problem identity and improvement rather than pursuing single variable solutions. This is not an automatic process and easy approach to apply. The role of consultants acting from the gestalt organizational development draw from the catalytic style which centers on helping on helping the client address problems by analyzing and interpreting data related to problem improvement of issues. However, the responsibility for solutions and decision making remains with the client. Drawing contributions from phenomenological research consultant-client collaboration takes a fresh perspective towards the phenomenon under examination, adopting a transcendental means, in which everything is perceived freshly, as if for the first time (Moustakas, 1994, p.34).

The model four consulting intervention is examined from a complexity perspective (Shaw, 1997), illustrates a model describing a consulting assignment undertaken by the author and a colleague. An example is illustrated where the consultants were presented with the structural problem confronting the company. Rather than starting from a prescriptive intervention a perspective which assumes problem identity and solving as a linear progression, the intervenors started from conversing with cliental group to gain wider understanding of the organizational and culture change. As observed by the consultant intervenors, the round table sitting style allowed participants to discover and create opportunities to discuss with each other lively issues within the formally and informally working environment (p.240). As suggested by the intervenors working from a complex adaptive system allows organizational knowledge to emerge in unpredictable within the edge of chaos conditions.

Using the complexity perspective processes as already outlined above (Shaw, 1997, p.241) the consultants intervenors worked within the cliental shadow systems in collaborative approaches, which resulted in people having to deal with disorderly paradoxes and contradictions. This perspective allowed change and learning to emerge creatively rather than as planned from intended state to another. Drawing from the theory-research-development -practice cycle, the contribution of consulting from a complexity perspective provides insightful challenges and opportunities of identifying problem issues within practice and developmental learning that emerges from experimentation and adaptation. As outlined by (Rollinson, 2008) consultants orienting the emergent approach theory reject that change follows a set of pre-planned steps due to constant environmental uncertainties. From this perspective theorists and practitioners orienting consulting from a complexity perspective view change as an ongoing, continuous, and open-ended process of transitions, rather than as predetermined intervention procedures. Consequently, consultants working from the complexity approach adopt a process orientation and act as process counsellors who act as problem sensors and facilitators while encouraging problem solving capabilities of the organization and creativity to emerge from uncertainties and dilemmas experiencing. From the phenomenology understanding of organizational consulting from a complexity perspective, experiences of consultant-clients are documented as emergence processes. This perspective provides new ways of phenomenological experiences of consultants-clients working collaboratively within the tension of the legitimate and shadow systems, and emerging feedback loops as shown in the knowledge creation outcomes of the consulting model four approach.

The model five consulting intervention as contextual and collaborative learning is a practice-based approach. It reflects my own consulting journey in Collaborating Consulting that I founded in Switzerland to facilitate intervention changes and development with various cliental business and organizations. Collaborating Consulting is an intervention centered on contextual and collaborative processes and outcomes of working with clients. It helps clients to co-create with consultants anticipated preferred intervention outcomes. The consultant role is to clarify, support and empower clients to design solutions conducive to their business needs. As already outlined this approach of my consulting approach is informed from theories of diagnostic and dialogic intervention, in which I suggest that effective organizational consulting is the ability to collaborate with clients in ways that improve and improvise organizational contextual systems. The CCM practice and inquiry as an epistemology has increased my understanding of others and self within my professional and personal life. In most cases the work of consulting is viewed as only concerned with solving or improving cliental problems and less with science. Since I view myself as a practitioner-researcher the practice -science dichotomy is collapsed. Drawing from the theory-research-development-practice cycle (See Figure 2), my organizational consulting becomes a place to reflect these domain cycles as contributions towards the development of my professional practice. Schön (1983) suggests that professional development emerges as an epistemology of practice consisting of problem solving and problem identity issues which practitioners do bring to situations of uncertainty, instability, uniqueness, and value conflict (p.49). Schon note that a practitioner reflection on their knowing in practice and while in the action to make sense of situations of uncertainty one experiences (p.61).

Therefore, the CCM research inquiry as outlined in my methodology position me as orienting social constructionist approach, process-oriented consultancy and task-oriented consultancy interventions who integrates practitioner researcher knowledge to be applied in organizational consulting. Drawing from my expertise areas as organizational change and development, I offer specific and concrete recommendations to the client. Additionally, I use the process approach in working with clients in approaches that are personal, involved and enabling knowledge creation that construct meanings from contextual and collaborative possibilities. Gummesson (2000) also noted the concept of management action science as; (1) Action scientists acting as change agents either as academic researchers or external management consultant; (2) Action science as dual roles of contributing to the client and contributing to science; (3) Action science being interactive showing collaboration between researchers and client personnel to engage continuous learning and improvements through problem solving; (4) The understanding developed during an action science project being holistic, while recognizing complexities; (5) Action science as applicable to the understanding, planning, and implementation of change in business firms and organizations. Gummesson (2000) proposed management action science concepts opens phenomenological depth of capturing and understanding experiences to construct what Schön referred to as possibilities in constructing a new way of setting the problem.

Discussion and Recommendations

The aim of the study was to provide insights on the theoretical and practice impacts that influence the work of organizational consultants and types of interventions enacted. Drawing from the theory-research-development-practice cycles, five consulting models were discussed to understand considerations of the contextual and collaborative knowledge guiding consultants-cliental relating and intervention choices. Hence five consultation interventions approaches were identified such as the: dialogic perspective; consultant-client interface; gestalt organizational development; complexity perspective and contextual and collaborative analysis. This is not to suggest that the above intervention approaches imply finality. In brief it is only to suggest that organizational consultants are guided by the theoretical assumptions they bring to their work demands and their goals are guided by intervention methods they choose. To gasp the challenges of organizational consulting in business and organizational domains the multiple consultant perspective (MCP) would need to be adopted. The MCP allow broader understanding of the contextual and collaborative issues in consulting rather than only adopting the planned change approaches in their consultative roles.

The Multiple Consultant’s Perspective

Consultants working from the multiple consultant perspective will entail working with clients that reflect multiple possibilities of intervention approaches. From my findings the descriptions of the five model examples of consulting reflect choices of various intervention approaches applied. However, it may also be possible that several interventions are applied during a consulting project. The multiple consultant perspective adds value when it reflects intervention approaches to organizational consulting as possibilities of meanings created within experiences and perspectives of consultant-client learning. Such perspectives would include rich accounts of conceptualizing the organizational consulting field using contextual, collaborative, complex and dialogic possibilities given diversities of the cultural, social, political, and environmental realities that confront consulting intervenors. Consultants drawing from the multiple perspective will bring the following reflexive analysis of organizational consulting learning interventions as outlined in the questions guiding my study.

- Using multiple methods in consulting intervention: In response to question 1, it is evident from literature review that theory and practice dimensions in organizational consulting are often seen as serving different purposes. However as already stated, the theory, research, development, and practice illustrate application of inquiry methods that contribute advancement of knowledge for both researchers and practitioners (Swanson and Holton, 2005) drawn from qualitative methods. Extended strategies for conducting research in organizational consulting can also incorporate the quantitative methods and mixed methods to illustrate knowledge created in varieties of consulting practices. Moreover, in this study, the qualitative methods were used to advance management action science (Gummesson, 2000) and phenomenological essences to shared experiences contributed as insights towards understanding organizational consulting.

- Applying innovative consulting intervention: In response to question 2, it is important to note that since there is no one universal intervention appropriate for all consultant-client situations. Therefore, innovative consultants may use varieties of approaches that add value towards cliental concerns. By innovation I mean the ability to design consulting interventions that promote discovery and innovation. In this respect I define consultant-client relating as joint efforts aimed towards developing innovative business and management practices that are context and collaborative centered. Accordingly, innovative consultants need to be innovative and creative, not necessarily repeating methods that worked in other consulting or organizational contexts but learn and change the solution paths as consultancy unfolds (London & Diamante,2018, p.21).

- Understanding the role of theory intervention: In response to question 3, it was important to note from the study of five different consulting models that each organizational consulting was informed from different theoretical assumption. From this observation and based in my consulting experiences, the role of theory guiding the consultant intervention need to be made explicit. Therefore, it is important that consultants articulate theories guiding their work or intervention activities. Although from a cliental perspective outcome of theoretical processes used in consultation intervention are only useful to the degree that practical issues of concern are addressed or improved. However, the role of theory intervention in consulting reflects principles that guided the actions of the change agents. Gummesson (2000) suggested theory of knowledge influencing management research consultants as; (1) general knowledge of theories, models concepts and techniques, methods; (2) specific knowledge of institutional conditions and social patterns; (3) personal attributes of consultants such as intuition, creativity, vitality, and social ability (p.73). From an organizational development (OD) consulting (Massarick and Pei- Carpenter (2002) theoretical perspectives of consultants are described beyond the techniques they employ but as several levels of self-concept identified as: simple labels, the acceptable present, the acceptable past, the unacceptable present, the unacceptable past. (p.30). Accordingly, these levels give content to what we are as human beings with consequences to our life and work as consultants. My practitioner-research roles in organizational consulting and values are influenced from behavioral science and organizational psychology approaches. My position as organizational consultant is influenced from organizational theory (Jones, 2013) which is centered an organizational change approach. My primary focus of work with clients becomes that of developing collaborative design processes that move organizations from their present state towards desired future states to increase their effectiveness.

- Developing practice and research: In response to question 4, the goal of my study was to provide insights in the development of research and practice of organizational consulting. Research that takes the nature of practice as its central focus is called practice-led research. Practice-led research is concerned with the nature of practice and leads to new knowledge that has operational significance for that practice. Although I have embedded my study from theory contributions, the primary focus of my research is to advance knowledge about organizational consulting practice. Drawing from practice-based theory (Erden et al, 2014) scholars studying a phenomenon with a knowledge perspective are concerned about the nature of knowledge, the ways of knowing and knowledge processes related to actions related to phenomenon (p.714). Building from the above perspective, I have argued in this study that research in organizational consulting must be understood within its theoretical assumptions and that selection of intervention approaches are determined from application of contextual and collaborative model of analysis.

- Quality evaluation of practice and research: The quality evaluation is focused on key features that emerge from my consulting-cliental interaction based on the contextual and collaborative model (CCM) that I have already discussed in my study as impacting the quality of such an intervention in organizational consulting inquiry. The following four points specify my quality evaluation concept: (1) Quality in analysis and interpretation – engaging business or management cliental issues using my six key elements for facilitating intervention and learning in organizational consulting practice; (2) Quality in practice – drawing from a multiple consultative perspective to create and develop consulting intervention activities and actions using my reflexive analysis approach as outlined in my study questions ; (3) Quality in research – integrating the four domains of theory, research, development and practice to advance organizational consulting improvements in ways beneficial to clients, researchers and practitioners; (4) Quality in experience – using the phenomenological analysis to capture consultant-client essence of the experience and also describe essence of the lived phenomenon. Having outlined my theory and researcher roles in the analysis and interpretation of organizational consulting learning and practice, the final section provides my understanding and reflections on the application to my research.

Conclusion and Implications: A Professional and Personal Reflection

Despite the complexities of organizational consulting that change agents encounter and experience in the field the underlying conception of a multiple consultant perspective remains a challenge and possibility to implement. The thesis research I conducted on organizational change and development using contextual and collaborative change approaches and methodological review clarified my thinking and provided the foundation for the design and elaboration of the theory and practice of this study focusing on organizational consulting. The findings of my study confirmed that consultants are guided by various theories and intervention approaches they bring to their practice. This demonstrates the potential of future practitioner researchers to examine further the scope of organizational consulting interventions that are diverse and multidisciplinary. The limitation of this sample study is that it focused on analyzing few organizational consulting models. This was due to the constraints of time, so that it was not possible to review many consulting cases. Moreover, emerging from the comparison of the consulting cases provided a deeper understanding of the knowledge creation within their theoretical frameworks and practice domains of the consultant-client context.

The importance of using theory in qualitative research provided multiple insights in doing the study. The consulting practice was conceptualized from a qualitative study to gain a multiple understanding of varieties of intervention approaches. The application of the theory, research, development (Swanson & Holton, 2005) provided lens through which I could understand the multiple meanings of research in organizational consulting and with the intent of developing a systematic application of inquiry methods working to advance the knowledge by researchers and practitioners. Similarly (Creswell, 2013) support the phenomenology inquiry to capture the description of the essence and understand the essence of experience. My goal in using theory as a foundation was aimed to justify my work and contribute qualitative research outcomes that advance interactivity of theory and practice in organizational consulting.

Attending to the theory in research design and implementation in the field of organizational consulting still draws a lot from classical models of intervention. All consultants advocate diagnosis as a justification acting in organizations. However (Weisbord, 2005) has proposed alternatives to traditional consultation as considerations toward cultivating what he calls third wave managing and consulting centered on four practices. The four practices are to; (1) assess the potential for action; (2) get the whole system into the room; (3) focus on the future; and (4) structure tasks that people can do themselves (p.71). He argues these practices focus on enacting productive community rather than just trying to find the right solutions. These ideas have stimulated my own perspectives and renewed position in my organizational consulting journey as informed from theory, research, development, and practice reflections. I hope this study has illustrated the benefits of using this integrated model to illuminate insights on organizational consulting. (Swanson and Holton, 2005) has outlined the benefits of using this model as; (1) Each of the four domains contributes to effective practice in organizations; (2) Exchange among the domains is multidirectional and improvements in the profession can improve whether one begins with theory, research, development, or practice (p.7). It is important to note that management research may orient either towards rationalistic or interpretive perspectives. As noted by (Sandberg and Targama, 2007) rationalistic perspective assumptions view subject and reality as two independent entities contrary to interpretative perspective which views understanding of reality as socially constructed relationally with others based on shared experiences and exchanged interactions. My position as organizational consulting analyst is influenced from the interpretive perspective which has influenced the CCM as a grounded methodology shaping my consulting practice.

Moreover, as a practitioner researcher who has taken the role of consulting as organizational change and development practitioner, being reflexive of the qualitative influences of the four domains of theory, research, development, and practice has deepened my understanding of the consulting practice in which I function. It has also deepened my understanding of the importance of theory in management research as integral to constructing contextually and collaborative consulting practices. Weick (1989) suggests the process of theory building as disciplined imaginations that view research and theorizing as creative, matter of heuristics and associative thinking. Finally, as a practitioner researcher my organizational consulting reflections integrates multiple theories and has centered on working with clients from a contextual and collaborative approach and multiple consultative perspective as an intervention.

Therefore, it is my recommendation that current and future practitioner researchers in consulting practices act as continuous learners, adopt analytic and interpretive skills created within contextual and collaborative client systems of understanding. Additionally, and more important it is my hope that practitioner researchers of organizational consulting would use reflexivity to develop their theory and practice underpinnings. As practitioner researchers of organizational consulting the skill to reflect multiple choices of intervention consulting approaches applied and demonstration of quality practice impacts is of particular importance.

Bibliography:

Armenakis, A., A. & Harris, S.G. (2009). Reflections: Our journey in organizational change research and practice, Journal of Change Management, 9 (2), 127-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697010902879079

Argyris, C. (1971). Intervention theory and method. A behavioural science views. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company.

Bell, E. & Thorpe, R. (2013). A very short, interesting, and reasonably cheap book about management research, Sage.

Block, P. (2011). Flawless consulting. A guide to getting your expertise used. 3rd ed. Jossey Bass / Pfeiffer.

Burno, A.F. & Jamieson, D. (2010). Consultation for organizational change. Information Age Publishing.

Bushe, G.R. & Marshak, R.J. (2009). Revision organizational development: Diagnostic and dialogic premises and patterns of practice, Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 45 (3), 348-368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886309335070

Caldwell, R. (2003). Models of change agency: A fourfold classification, British Journal of Management, 14 (2), 131-142.

Cockman, P., Evans, B., and Reynolds, P. (1992). Client -centred consulting. McGraw Hill.

Creswell, J.W. (2013). Qualitative inquiry & research design. 3rd ed. Sage.

Crowther, D. & Lancaster, G. (2009). Research methods: A concise introduction to research in management and business consultancy. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Cummings, T.G. & Worley, C.G. (2009). Organizational development & change. 9th ed. South-Wetern Cengage Learning.

Czerniawska, F. (2002). Value-based consulting. Palgrave McMillan.

Dooley, K.J. (1997). A complex adaptive system model of organizational change, Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and life Sciences, 1 (1), 69 – 97.

Erden, Z., Schneider, A., Von Krogh, G. (2014). The multifaceted nature of social practices: A review of the perspectives on practice -based theory building about organizations. European Management Journal 32, 712-722, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2014.01.005

Gergen, K. J. & Thatchenkery, T. J. (2004). Organizational science as social construction: Postmodern potentials. Journal of Applied Behavioural Science, 40 (2), 228-229.

Gordon, J. R. (1999). Organizational behaviour: A diagnostic approach. 6th ed. Prentice Hall.

Gummesson, E. (2002). Qualitative methods in management research. 2nd ed. Sage Publications.

Hayes J. (2002). The theory and practice of change management. Palgrave.

Hodges, J. (2017). Consultancy, organizational development, and change. Kogan Page.

Holbeche, L. (2006). Understanding change. Butterworth-Heinemann.

Jacobson, N. Butterill, D.,Goering, P. (2005). Consulting as a strategy for knowledge transfer, A Multidisciplinary Journal of Population Health and Health Policy, 83 (2), 299-321. https: //doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005. 00348.x

Jones, G.R. (2013). Organizational theory, design, and change. Pearson.

London, M. & Diamante, T. (2018). Learning interventions for consultants. American Psychological Association.

Lowman, R.L (2012). The scientific -practitioner consulting psychologist. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 64 (3), 151-156.

Lowman, R.L. (2016). An introduction to consulting psychology: Working with individuals, groups, and Organizations.American Psychology Association, https://dx.doi.org/10.1037/14853-000

MacIntosh, R., Beech, N., Antonacopoulou, E., Sims, D. (2012). Practicing and knowing management: A dialogic perspective. Management. Management Learning, 0 (0), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507612452521

Magretta, J. (2002). What management is. Harper Collins Business.

Marshak, R.J. & Grant, D. (2008). Organizational discourse and new organization development Practices. British Journal of Management, 19, 7-19.

Martin, J. & Fellez, M. (2010). Organizational behaviour and Management, 4th ed. South - Western Cengage Learning.

Massarik, F. & Pei-Carpenter, M. (2002). Organizational development and consulting. Jossey-Bass / Pfeiffer.

Miles, M.B.,Huberman, A.M.,& Saldana, J. ( 2020). Qualitative data analysis, 4th ed. Sage.

Mintzberg, H. (2009). Henry Mintzberg Managing, Prentice Hall.

Moustakas, C. (1994). Phenomenological research methods. Sage.

Rollinson, D. (2008). Organizational behaviour and analysis, 4th ed. Prentice Hall.

Sandberg, J. & Targama, A. (2007). Managing understanding in organizations. Sage Publications.

Saner, R. (1999). Organizational consulting: What can gestalt approach can learn from off-off broadway theatre, Gestalt Review, 3 (1),6-21.

Schein, E.H. (1988). Process consultation. 2nd ed. Addison – Wesley Publishing Company.

Schön, D.A. (1983). The reflective practitioner. Basic Books.

Stokes, P. (2011). Key concepts in business and management research methods. Palgrave Macmillan.

Swanson, R.A. & Holton, E.F. (2005). Research in organizations: Foundations and methods of inquiry Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Tomenendal, M. (2007). The consultant-client interface: A theoretical introduction to the Hot Spot of management consulting, Business, and management, 31 (8), 1-7.

Tolbert, M.A. R. (2004). What is Gestalt organization & systems development? OD practitioner, 36 (4), 6-10.

Tracy, S., J. (2007). Taking the plunge: A contextual approach to problem-based research. Communication Monographs, 74 (1), 106-111.

Van Manen, M. (2014). Phenomenology of practice: Meaning-giving methods in phenomenological research and writing. Left Coast Press.

Viljoen, R. (2015). Organizational change and development. Knowres Publishing.

Weick, K.E. (1989). Theory construction as disciplined imagination, Academy of Management Review, 14 (4), 416-531.

Weisbord, M.R. (2005). Toward third wave managing and consulting. In W.L. French; C.H. Bell & R.A. Zawacki (Eds.), Organizational Development and Transformation: Managing Change, 63-79 6th ed. McGraw-Hill.

Wickham, P., A. (2004). Management consulting, 2nd ed. Pearson Education.

Author: Sydney Moyo, student LIGS University

Approved by: Amr Sukkar, lecturer LIGS University